POL Politiek

Discussies en diepgaande gesprekken over de politiek in de breedste zin van het woord kun je hier voeren.

Lets show me.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:15 schreef remlof het volgende:

[..]

Dat heb je met meer woorden, zag ik in dat andere topic

"Fifty years ago the Leningrad street taught me a rule - if a fight is inevitable, you have to throw the first punch."

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Gerrit Zalm, wat was dat toch een humoristisch en goeie minister van financien.

"Fifty years ago the Leningrad street taught me a rule - if a fight is inevitable, you have to throw the first punch."

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Ik zit te wachten op Remlof, ben altijd benieuwd naar fouten.

"Fifty years ago the Leningrad street taught me a rule - if a fight is inevitable, you have to throw the first punch."

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Kennelijk niet..quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:36 schreef phpmystyle het volgende:

Ik zit te wachten op Remlof, ben altijd benieuwd naar fouten.

"He who gives up freedom for safety deserves neither" Benjamin Franklin

?quote:

"Fifty years ago the Leningrad street taught me a rule - if a fight is inevitable, you have to throw the first punch."

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:01 schreef fokthesystem het volgende:

Mooi topic wel, Waarom discussiëren jullie op dit forum? van toepassing ook op elke SC :

[..]

Hulde voor de OP, deze reactie is echter nOg beter. Hij sluit aan bij de 7 types 'usenet gebruikers' die posten op fok.(En andere fora)

Enig idee heb ik wel: 'stalken' en als het antwoord uitblijft dan kan je de niet-reageerder daar telkens mee confronteren, alle andere punten zijn dan n.v.t. Zeg maar een a-bom in het 'spelletje' rock, scissors, paper en dan aangevuld met a-bom, die alle andere 3 nuked

Verder is 'afbranden' van anderen, vliegen afvangen iets van de mindere broeders die op deze wijze 'puur natuur, basaal, instinctief' zich toch groter, belangrijker willen voelen door een ander te kleineren.

Volkorenbrood: "Geen quotes meer in jullie sigs gaarne."

Ik wees je (heel subtiel) al op een foutquote:

"He who gives up freedom for safety deserves neither" Benjamin Franklin

Die is dan niet overgekomen.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:41 schreef Whiskers2009 het volgende:

[..]

Ik wees je (heel subtiel) al op een fout

"Fifty years ago the Leningrad street taught me a rule - if a fight is inevitable, you have to throw the first punch."

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Kent U deze nog-nog-nog?quote:

quote:Op zondag 12 december 2010 23:39 schreef phpmystyle het volgende:

Dit topic prevaleer ik boven die van Monolith.

Op donderdag 11 oktober 2012 19:49 schreef Tem het volgende:

Bis bis bis

Op maandag 17 december 2012 22:25 schreef KoosVogels het volgende:

Wij krijgen niks voor kerst van de baas. Alleen een trap onder de reet en een stuk steenkool.

Bis bis bis

Op maandag 17 december 2012 22:25 schreef KoosVogels het volgende:

Wij krijgen niks voor kerst van de baas. Alleen een trap onder de reet en een stuk steenkool.

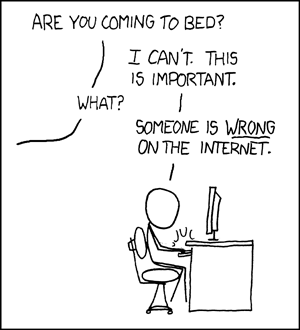

Het is natuurlijk wel de essentie wanneer je als naïeve tiener begint te discussiëren op internet. Je denkt nog dat mensen voor rede vatbaar zijn en dat ze, ondanks dat ze een andere mening zijn toegedaan, op z'n minst openstaan voor correctie van feitelijke onjuistheden en eventueel op basis daarvan geneigd zouden zijn standpunten enigszins te nuanceren of herzien. Niets is minder waar natuurlijk. Een tijdje terug was daar nog wel een aardig onderzoekje over:quote:

quote:Elections are a time for smearing, and the Mails desperate story about Nick Clegg and the Nazis is my favourite so far. Generally the truth comes out, in time. But how much damage can smears do?

A new experiment published this month in the journal Political Behaviour sets out to examine the impact of corrections, and what they found was far more disturbing than they expected: far from changing peoples minds, if you are deeply entrenched in your views, a correction will only reinforce them.

The first experiment used articles claiming that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction immediately before the US invasion. 130 participants were asked to read a mock news article, attributed to Associated Press, reporting on a Bush campaign stop in Pennsylvania during October 2004. The article describes Bushs appearance as a rousing, no-retreat defense of the Iraq war and quotes a line from a genuine Bush speech from that year, suggesting that Saddam Hussein really did have WMD, which he could have passed to terrorists, and so on. There was a risk, a real risk, that Saddam Hussein would pass weapons or materials or information to terrorist networks, and in the world after September the 11th, said Bush: that was a risk we could not afford to take.

The 130 participants were then randomly assigned to one of two conditions. For half of them, the article stopped there. For the other half, the article continues, and includes a correction: it discusses the release of the Duelfer Report, which documented the lack of Iraqi WMD stockpiles or an active production program immediately prior to the US invasion.

After reading the article, subjects were asked to state whether they agreed with the following statement: Immediately before the U.S. invasion, Iraq had an active weapons of mass destruction program, the ability to produce these weapons, and large stockpiles of WMD, but Saddam Hussein was able to hide or destroy these weapons right before U.S. forces arrived. Their responses were measured on a five-point scale ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree.

As you would expect, those who self-identified as conservatives were more likely to agree with the statement. Separately, meanwhile, more knowledgeable participants (independently of political persuasion) were less likely to agree. But then the researchers looked at the effect of whether you were also given the correct information at the end of the article, and this is where things get interesting. They had expected that the correction would become less effective in more conservative participants, and this was true, up to a point: so for very liberal participants, the correction worked as expected, making them more likely to disagree with the statement that Iraq had WMD when compared with those who were very liberal but received no correction. For those who described themselves as left of center, or centrist, the correction had no effect either way.

But for people who placed themselves ideologically to the right of center, the correction wasnt just ineffective, it actively backfired: conservatives who received a correction telling them that Iraq did not have WMD were more likely to believe that Iraq had WMD than people who were given no correction at all. Where you might have expected people simply to dismiss a correction that was incongruous with their pre-existing view, or regard it as having no credibility, it seems that in fact, such information actively reinforced their false beliefs.

Maybe the cognitive effort of mounting a defense against the incongruous new facts entrenches you even further. Maybe you feel marginalised and motivated to dig in your heels. Who knows. But these experiments were then repeated, in various permutations, on the issue of tax cuts (or rather, the idea that tax cuts had increased national productivity so much that tax revenue increased overall) and stem cell research. All the studies found exactly the same thing: if the original dodgy fact fits with your prejudices, a correction only reinforces these even more. If your goal is to move opinion, then this depressing finding suggests that smears work, and whats more, corrections dont challenge them much: because for people who already agree with you, it only make them agree even more.

Volkorenbrood: "Geen quotes meer in jullie sigs gaarne."

Met recht een SC vanavond... Waar is de rest???

"He who gives up freedom for safety deserves neither" Benjamin Franklin

Je weet duidelijk niet waar je het over hebt.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:27 schreef phpmystyle het volgende:

Gerrit Zalm, wat was dat toch een humoristisch en goeie minister van financien.

http://zembla.vara.nl/Dos(...)067&cHash=ebbf9b9103

Mede mogelijk gemaakt door Gerrit Zalm.

Vergis je niet, onder zijn bewind zijn er waterdichte begrotingen afgeleverd. En dat we in die euro zitten hebben we niet alleen te danken aan Zalm.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:52 schreef Holograph het volgende:

[..]

Je weet duidelijk niet waar je het over hebt.

http://zembla.vara.nl/Dos(...)067&cHash=ebbf9b9103

Mede mogelijk gemaakt door Gerrit Zalm.

"Fifty years ago the Leningrad street taught me a rule - if a fight is inevitable, you have to throw the first punch."

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Vladimir Putin

“To forgive the terrorists is up to God, but to send them there is up to me.”

Vladimir Putin

Hij doelt meer op de koers gok ik.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:54 schreef phpmystyle het volgende:

[..]

Vergis je niet, onder zijn bewind zijn er waterdichte begrotingen afgeleverd. En dat we in die euro zitten hebben we niet alleen te danken aan Zalm.

Op donderdag 11 oktober 2012 19:49 schreef Tem het volgende:

Bis bis bis

Op maandag 17 december 2012 22:25 schreef KoosVogels het volgende:

Wij krijgen niks voor kerst van de baas. Alleen een trap onder de reet en een stuk steenkool.

Bis bis bis

Op maandag 17 december 2012 22:25 schreef KoosVogels het volgende:

Wij krijgen niks voor kerst van de baas. Alleen een trap onder de reet en een stuk steenkool.

Gerrit Zalm had zijn tijd dan ook mee. Het kabinet kreeg alleen maar meevallers 'te verwerken', logisch dat je dan een goede begroting krijgt.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:54 schreef phpmystyle het volgende:

[..]

Vergis je niet, onder zijn bewind zijn er waterdichte begrotingen afgeleverd. En dat we in die euro zitten hebben we niet alleen te danken aan Zalm.

Je moet gewoon toegeven, gewoon toegeven dat het simpele zielen zijn. Lach ze uit, minacht ze, maar probeer ze niet te overtuigen, er zijn leukere dingen.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:51 schreef Monolith het volgende:

[..]

Het is natuurlijk wel de essentie wanneer je als naïeve tiener begint te discussiëren op internet. Je denkt nog dat mensen voor rede vatbaar zijn en dat ze, ondanks dat ze een andere mening zijn toegedaan, op z'n minst openstaan voor correctie van feitelijke onjuistheden en eventueel op basis daarvan geneigd zouden zijn standpunten enigszins te nuanceren of herzien. Niets is minder waar natuurlijk. Een tijdje terug was daar nog wel een aardig onderzoekje over:

[..]

En de 21 miljard die Zalm verdiende met de grote omwissel truc.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:55 schreef Holograph het volgende:

[..]

Gerrit Zalm had zijn tijd dan ook mee. Het kabinet kreeg alleen maar meevallers 'te verwerken', logisch dat je dan een goede begroting krijgt.

Ach, ook op het internet zijn er nog wel genoeg mensen te vinden die een coherent betoog kunnen samenstellen, bereid zijn tot de nodige nuancering, interessante kritiek kunnen leveren, enzovoort. Dat percentage ligt echter niet bijster hoog. Ik moet ook zeggen, met het risico een oude lul te lijkenquote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:55 schreef Monidique het volgende:

[..]

Je moet gewoon toegeven, gewoon toegeven dat het simpele zielen zijn. Lach ze uit, minacht ze, maar probeer ze niet te overtuigen, er zijn leukere dingen.

Volkorenbrood: "Geen quotes meer in jullie sigs gaarne."

Ik ben naar The New Kids geweest.quote:Op maandag 20 december 2010 21:51 schreef Whiskers2009 het volgende:

Met recht een SC vanavond... Waar is de rest???

Op zaterdag 22 januari 2011 19:19 schreef voice-over het volgende:

Om het woord naargeestig te parafraseren: TomLievense schrijft naargeestige stukjes

Om het woord naargeestig te parafraseren: TomLievense schrijft naargeestige stukjes

Op

Op