W&T Wetenschap & Technologie

Een plek om te discussiŽren over wetenschappelijke onderwerpen, wetenschappelijke problemen, technologische projecten en grootse uitvindingen.

http://deredactie.be/cm/vrtnieuws/wetenschap/1.1995171quote:Koloniale dammen sturen evolutie van vissen in Connecticut

do 12/06/2014 - 17:05 Alexander Verstraete

Nadat het fenomeen eerder al bij de elft was vastgesteld, blijkt nu ook de evolutie van de zonnebaars danig beÔnvloed door de koloniale dammen die 300 jaar geleden op de rivieren en de meren van de Amerikaanse staat Connecticut zijn gebouwd. Dat blijkt uit onderzoek aan de Landbouwuniversiteit in Zweden.

quote:The game theory of life

An insight borrowed from computer science suggests that evolution values both fitness and diversity

In what appears to be the first study of its kind, computer scientists report that an algorithm discovered more than 50 years ago in game theory and now widely used in machine learning is mathematically identical to the equations used to describe the distribution of genes within a population of organisms. Researchers may be able to use the algorithm, which is surprisingly simple and powerful, to better understand how natural selection works and how populations maintain their genetic diversity.

By viewing evolution as a repeated game, in which individual players, in this case genes, try to find a strategy that creates the fittest population, researchers found that evolution values both diversity and fitness.

Some biologists say that the findings are too new and theoretical to be of use; researchers don't yet know how to test the ideas in living organisms. Others say the surprising connection, published Monday in the advance online version of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, may help scientists understand a puzzling feature of natural selection: The fittest organisms don't always wipe out their weaker competition. Indeed, as evidenced by the menagerie of life on Earth, genetic diversity reigns.

"It's a very different way to look at selection," said Stephen Stearns, an evolutionary biologist at Yale University who was not involved in the study. "I always find radically different ways of looking at a problem interesting."

The algorithm, which has been used to solve problems in linear programming, zero-sum games and a dozen other sophisticated computer science problems, is used to determine how an agent should weigh possible strategies when making a series of decisions. For example, imagine that you have 10 financial experts giving you advice on how to invest your savings. Each day you have to choose to follow one of them. At the start of the investment period, you know nothing about how well each expert performs. But every day, the multiplicative weights update algorithm, as it is called, instructs you to boost the probability of choosing the experts who have given the best advice and decrease it for those who have performed poorly.

"If you do this day after day, at the end of the year, you will do almost as well as if you had followed the best expert from the beginning," said Christos Papadimitriou, a computer scientist at the University of California, Berkeley. "It's as if you were omniscient in the beginning, singling out the best expert and following their advice day after day."

Papadimitriou and his collaborators came across the connection between game theory and evolution when they were searching for a mathematical explanation of sex, which triggers new genetic diversity by mixing up the chromosomes from each parent. They were working with equations commonly used in population genetics, first developed nearly a century ago, that describe how the frequencies of certain genetic variations change with each generation. For example, plants that flourish in the current climate might dwindle as global warming alters conditions.

When they showed the equations to Umesh Vazirani, pictured, a computer scientist at Berkeley, he noticed parallels to a repeated coordination game — a scenario in game theory in which success depends on the players choosing mutually beneficial options. As an example, consider a situation in which two prisoners are tempted to turn on each other. If one talks, both lose; if neither talks, both win. Neither prisoner knows what the other will do. (This scenario is different than the well-known prisoner's dilemma.)

Viewing the algorithm through the lens of evolution, genes are the players, and each gene has a number of different strategies in the form of genetic variations, or alleles. One variant of a gene might make a plant tolerate warmer temperatures or drier soil, for instance. The game is played over and over again; at the end of each round, the gene, or player, evaluates how well each of its alleles performed in the current genetic environment and then boosts the weight of the good performers and downsizes the weight of poor performers.

The researchers said the findings will provide a new way to examine the role of sex in evolution. For example, Papadimitriou said he believes that part of its role is to carry out the multiplicative weights update algorithm, though he hasn't yet proven this mathematically.

Traditional applications of game theory to evolution examine how evolutionary processes shape an individual's behavior. They have also been used to study the evolution of altruism and other properties. "But here, we're talking about something completely different," said Adi Livnat, a biologist at Virginia Polytechnic Institute in Blacksburg, Va., who collaborated on the study. The new study focuses on genes rather than individual organisms, and on the genetic makeup of the population instead of behavior.

The approach could illuminate a long-standing mystery in population biology. Just as in the financial world, where it's best to keep a diversified portfolio, Vazirani and his collaborators found that the algorithm values both fitness and diversity. You might be tempted to place all your money on a soaring stock. But if circumstances change and that stock starts to tank, you're better off having invested in a more balanced selection. Similarly, an organism's genes may be perfectly tailored to a particular set of environmental conditions, but if those conditions change, a genetically diverse population is more likely to survive.

"Evolution is, of course, interested in performance," Papadimitriou said.

"But it's also interested in hedging its bets, keeping around a lot of genetic diversity because who knows what will come next."

Evolutionary biologists know that in practice, a genetically diverse population is often more resilient than a homogeneous one because it is better able to respond to changing environments. But they have struggled to explain how such diversity is maintained. In the short term, one would expect diversity to drop as the fittest members of a population spread, knocking out the weaker, genetically dissimilar members. How do long-term needs surmount the short-term pressures?

The findings provide a "speculative suggestion" for how this might happen, though the authors don't propose a specific mechanism, said Nick Barton, a biologist at the Institute of Science and Technology in Austria who was not involved in the study. "I don't think it gives us the algorithm that can achieve the diversity we see on Earth in 3.5 billion years, when life first began," he said.

Stearns and others in the field say it's too soon to assess how the findings will affect our understanding of evolution. Even though the connection between different fields is interesting, "it does not actually help us understand biological evolution," said Chris Adami, a physicist and computational biologist at Michigan State University, who was not involved in the study. "Unless such a relationship allows you to say something new either in computer science or biology, it's just an observation."

Evolutionary biologists are often skeptical of mathematical insights from outsiders. Although mathematicians and computer scientists regularly publish in the field, biologists disagree over how much their contributions have done to shape it. "I think it will take some time to figure out how the paper plays out," Stearns said. "If this doesn't cause any new data to be gathered, then it won't be very important." Even if the findings don't prove relevant in the short-term, they might prove important over the long –term. Sometimes it can take decades before the right technology or approach arises to test a new theory, Stearns said.

The equations in the study are based on certain assumptions that may limit their applicability to the real world. For example, the equations don't account for mutations, which would introduce new alleles, or strategies, into the game. (Adding this factor makes the mathematics much more complex.) Some say this simplification is a serious drawback, while others maintain that it is not so important in the short term, when existing variations have the strongest impact. "What happens when you move away from the assumptions?" said Lee Altenberg, a senior fellow at the Konrad Lorenz Institute in Austria. "They have pinned a single point on the map. But to know whether that means anything, you have to start departing from that point."

One outcome of the analysis is likely to puzzle biologists. According to the standard view of evolution, the further a generation lies in the past, the less impact it has on the present — your ancestors from 1,000 years ago probably had less effect on your fitness than your grandparents. But if the Berkeley team's insights hold up, "it shows us that every past generation contributes equally to what happens in the next generation," Stearns said. "That's an intriguing and wildly implausible claim from the standpoint of regular evolution." Papadimitriou said his team was also perplexed by that outcome. "It is something that hopefully will make researchers rethink, revisit and interpret," he said.

"You can't really test these theorems in relation to real life," Barton said. "They are tools for getting intuition about how to understand evolution."

Evolution and entropy

One of the surprising discoveries of Papadimitriou's study is that natural selection values not just fitness, but also genetic diversity, which in more technical terms is referred to as entropy. This view that evolution optimizes not just mean fitness but mean fitness and entropy is not well known, "but I think it's a deep observation," Adami said.

The Berkeley team isn't the first to highlight the role entropy might play in evolution. But until now, the subject has mainly been of interest to mathematicians rather than biologists.

"Applications of entropy in evolution have had a bad name, because they were very ill-defined," Barton said. "More recently, there have been some interesting, and much sounder, ideas, which make a link between fields that are addressing a similar issue: statistical physics and evolutionary biology both try to understand the overall properties of a complicated system, independent of the microscopic details."

These more recent results are mathematically sound, but they still don't connect well with existing biological understanding, he said. "So it's not clear to biologists how [the results] might help explain their open questions."

Free Assange! Hack the Planet

[b]Op dinsdag 6 januari 2009 19:59 schreef Papierversnipperaar het volgende:[/b]

De gevolgen van de argumenten van de anti-rook maffia

[b]Op dinsdag 6 januari 2009 19:59 schreef Papierversnipperaar het volgende:[/b]

De gevolgen van de argumenten van de anti-rook maffia

interessant en uitgebreid artikelquote:

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

03-07-2014

Nieuwe inzichten in de evolutie van veren

De vondst van een nieuw Archaeopteryx-fossiel geeft nieuwe inzichten in hoe en wanneer veren zijn ontstaan tijdens de evolutie van dino’s. Tevens helpt het fossiel de paleontologen om de primaire functies van veren te achterhalen. De website van het AD opende echter ten onrechte met ‘Oervogel kon waarschijnlijk wel vliegen’. Ook Nu.nl en Telegraaf.nl schreven een bericht met dezelfde toon.

Het nieuws dat oervogel Archaeopteryx wellicht kon vliegen is niet de hoofdboodschap van het wetenschappelijke artikel dat paleontologen vandaag publiceerden in Nature. De oorsprong en primaire functies van slagpennen, veren die moderne vogels slag- en stuwkracht geven, zijn in het artikel het belangrijkst.

Veren ontstonden in de eerste instantie niet om mee te vliegen.

Bron: Wikimedia Commons

Het nieuwe Archeopteryx-fossiel is het best bewaard gebleven exemplaar. Dit fossiel bleek niet alleen niet veren op de gevederde voorpoten en staart te hebben, maar over het gehele lichaam.

Het fossiel geeft daardoor nieuwe inzichten in het ontstaan van veren op het lichaam van dinosaurussen. Volgens de onderzoekers was de primaire functie van slagpennen bij tweepotige dinosaurussen niet om ermee te vliegen, maar om gevederde dino’s warm te houden. John de Vos, voormalig paleontoloog bij Naturalis, bevestigt dat. ‘Die slagpennen zijn ontstaan voor isolatie’, zegt hij. ‘En als die veren toch aanwezig zijn, kunnen ze ook voor andere dingen gebruikt worden, bijvoorbeeld om te kunnen gaan vliegen.’

Aanhoudende discussie

Dat Archaeopteryx kon vliegen, is ook niet iets wat met zekerheid gezegd kan worden. Wetenschappers, zo meldt ook het AD, zijn al sinds de ontdekking van Archaeopteryx in discussie over of het dier wel of niet kan vliegen. Die discussie bestaat vandaag de dag nog steeds. Het nieuwste exemplaar laat weliswaar zien dat het over een compleet verenpak beschikte, maar vliegen is een heel ander verhaal. Volgens De Vos is het een moeilijke kwestie. ‘Archaeopteryx heeft geen borstbeen, het bot waar bij moderne vogels de vliegspieren aan vastzitten’, zegt hij.

In 2003 toonden paleontologen met modellen aan dat Archaeopteryx van boom tot boom kon ‘vliegen’. Ze berekenden daarbij dat het dier maximaal afstanden van veertig meter kon afleggen. Dat ‘vliegen’ leek meer op glijden, en totaal niet op het vliegen wat moderne vogels doen.

Terecht meldt het AD zegt over dat ‘De assen van de vleugels in kracht vergelijkbaar zijn met die van moderne vogels’. Dat laten de onderzoekers zien in een grafiek. Maar dat betekent nog niet dat ze ook kunnen vliegen. ‘Om te kunnen vliegen heeft Archaeopteryx niet alleen veren nodig, maar ook vleugels’, zegt De Vos. Dat poten volledig bedekt zijn met veren, zorgt niet noodzakelijk voor vliegvermogen.

(newscientist.nl)

Nieuwe inzichten in de evolutie van veren

De vondst van een nieuw Archaeopteryx-fossiel geeft nieuwe inzichten in hoe en wanneer veren zijn ontstaan tijdens de evolutie van dino’s. Tevens helpt het fossiel de paleontologen om de primaire functies van veren te achterhalen. De website van het AD opende echter ten onrechte met ‘Oervogel kon waarschijnlijk wel vliegen’. Ook Nu.nl en Telegraaf.nl schreven een bericht met dezelfde toon.

Het nieuws dat oervogel Archaeopteryx wellicht kon vliegen is niet de hoofdboodschap van het wetenschappelijke artikel dat paleontologen vandaag publiceerden in Nature. De oorsprong en primaire functies van slagpennen, veren die moderne vogels slag- en stuwkracht geven, zijn in het artikel het belangrijkst.

Veren ontstonden in de eerste instantie niet om mee te vliegen.

Bron: Wikimedia Commons

Het nieuwe Archeopteryx-fossiel is het best bewaard gebleven exemplaar. Dit fossiel bleek niet alleen niet veren op de gevederde voorpoten en staart te hebben, maar over het gehele lichaam.

Het fossiel geeft daardoor nieuwe inzichten in het ontstaan van veren op het lichaam van dinosaurussen. Volgens de onderzoekers was de primaire functie van slagpennen bij tweepotige dinosaurussen niet om ermee te vliegen, maar om gevederde dino’s warm te houden. John de Vos, voormalig paleontoloog bij Naturalis, bevestigt dat. ‘Die slagpennen zijn ontstaan voor isolatie’, zegt hij. ‘En als die veren toch aanwezig zijn, kunnen ze ook voor andere dingen gebruikt worden, bijvoorbeeld om te kunnen gaan vliegen.’

Aanhoudende discussie

Dat Archaeopteryx kon vliegen, is ook niet iets wat met zekerheid gezegd kan worden. Wetenschappers, zo meldt ook het AD, zijn al sinds de ontdekking van Archaeopteryx in discussie over of het dier wel of niet kan vliegen. Die discussie bestaat vandaag de dag nog steeds. Het nieuwste exemplaar laat weliswaar zien dat het over een compleet verenpak beschikte, maar vliegen is een heel ander verhaal. Volgens De Vos is het een moeilijke kwestie. ‘Archaeopteryx heeft geen borstbeen, het bot waar bij moderne vogels de vliegspieren aan vastzitten’, zegt hij.

In 2003 toonden paleontologen met modellen aan dat Archaeopteryx van boom tot boom kon ‘vliegen’. Ze berekenden daarbij dat het dier maximaal afstanden van veertig meter kon afleggen. Dat ‘vliegen’ leek meer op glijden, en totaal niet op het vliegen wat moderne vogels doen.

Terecht meldt het AD zegt over dat ‘De assen van de vleugels in kracht vergelijkbaar zijn met die van moderne vogels’. Dat laten de onderzoekers zien in een grafiek. Maar dat betekent nog niet dat ze ook kunnen vliegen. ‘Om te kunnen vliegen heeft Archaeopteryx niet alleen veren nodig, maar ook vleugels’, zegt De Vos. Dat poten volledig bedekt zijn met veren, zorgt niet noodzakelijk voor vliegvermogen.

(newscientist.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

http://deredactie.be/cm/vrtnieuws/wetenschap/1.2046023quote:"AsteroÔde kwam op slecht moment voor dino's"

ma 28/07/2014 - 17:40 Joris Truyts

Als de asteroÔde die hun uitsterven veroorzaakte een paar miljoen jaar vroeger of later had ingeslagen, zou de aarde nu misschien nog steeds door dinosauriŽrs bevolkt worden. Die conclusie trekken onderzoekers in een nieuwe studie.

[ Bericht 0% gewijzigd door zakjapannertje op 29-07-2014 01:09:41 ]

Leuke typo in de titel.quote:Op dinsdag 29 juli 2014 00:09 schreef zakjapannertje het volgende:

[..]

http://deredactie.be/cm/vrtnieuws/wetenschap/1.2046023

Volkorenbrood: "Geen quotes meer in jullie sigs gaarne."

http://www.nationalgeogra(...)razendsnel-van-kleurquote:Onderzoekers laten vlinders van kleur verschieten

De evolutie van kleuren in de natuur is een raadselachtig proces, maar onderzoekers van Yale University hebben nu enig licht in de duisternis gebracht. Zij zijn erin geslaagd de kleur van vlindervleugels in minder dan een jaar tijd te veranderen.

19-08-2014

Afrikaanse pygmeeŽn ontstonden twee keer in evolutie

Zeker twee Afrikaanse pygmeeŽnvolken in Afrika zijn onafhankelijk van elkaar ontstaan in de loop van de evolutie, zo blijkt uit nieuw onderzoek.

De pygmeeŽn die in Oeganda leven, hebben hun kleine postuur te danken aan heel andere genen dan pygmeeŽn in West-Afrika.

Die bevinding suggereert dat een geringe lenge zo veel voordelen bood voor jagerverzamelaars in het Afrikaanse regenwoud dat pygmeeŽn meerdere malen zijn ontstaan in de loop van de evolutie.

Onderzoekers van de Universiteit van Montreal komen tot die conclusie in het wetenschappelijk tijdschrift PNAS.

DNA

De wetenschappers analyseerden de DNA-volgorde van leden van de Batwa, een pygmeeŽnstam in Oeganda. Ze richtten zich bij hun onderzoek vooral op delen van het genoom die van invloed zijn op lengte.

Vervolgens vergeleken ze het onderzochte DNA van de Batwa met de genen van de Baka, een pygmeeŽnstam in West-Afrika.

"In beide groepen was er een grote variatie in de regio's van het DNA die worden geassocieerd met een klein postuur, maar we vonden geen overlap tussen deze genen bij de twee twee stammen", verklaart hoofdonderzoeker Luis Barreiro op nieuwssite New Scientist.

Bukken

Barreiro vermoedt dat de genen voor de geringe lengte van verschillende pygmeeŽnvolken onafhankelijk van elkaar zijn ontstaan, omdat ze in dichte regenwouden leven. "Daar heb je het makkelijker als klein bent, zodat je niet hoeft te bukken om onder takken door te lopen."

Dat blijkt ook uit vervolgonderzoek waarbij de wetenschappers pygmeeŽn volgden tijdens hun tochten door het regenwoud. "De kleinste leden van de stammen hoefden minder te bukken, zweetten minder en verbruikten daardoor minder energie", aldus Barreiro.

Door: NU.nl/Dennis Rijnvis

(nu.nl)

Afrikaanse pygmeeŽn ontstonden twee keer in evolutie

Zeker twee Afrikaanse pygmeeŽnvolken in Afrika zijn onafhankelijk van elkaar ontstaan in de loop van de evolutie, zo blijkt uit nieuw onderzoek.

De pygmeeŽn die in Oeganda leven, hebben hun kleine postuur te danken aan heel andere genen dan pygmeeŽn in West-Afrika.

Die bevinding suggereert dat een geringe lenge zo veel voordelen bood voor jagerverzamelaars in het Afrikaanse regenwoud dat pygmeeŽn meerdere malen zijn ontstaan in de loop van de evolutie.

Onderzoekers van de Universiteit van Montreal komen tot die conclusie in het wetenschappelijk tijdschrift PNAS.

DNA

De wetenschappers analyseerden de DNA-volgorde van leden van de Batwa, een pygmeeŽnstam in Oeganda. Ze richtten zich bij hun onderzoek vooral op delen van het genoom die van invloed zijn op lengte.

Vervolgens vergeleken ze het onderzochte DNA van de Batwa met de genen van de Baka, een pygmeeŽnstam in West-Afrika.

"In beide groepen was er een grote variatie in de regio's van het DNA die worden geassocieerd met een klein postuur, maar we vonden geen overlap tussen deze genen bij de twee twee stammen", verklaart hoofdonderzoeker Luis Barreiro op nieuwssite New Scientist.

Bukken

Barreiro vermoedt dat de genen voor de geringe lengte van verschillende pygmeeŽnvolken onafhankelijk van elkaar zijn ontstaan, omdat ze in dichte regenwouden leven. "Daar heb je het makkelijker als klein bent, zodat je niet hoeft te bukken om onder takken door te lopen."

Dat blijkt ook uit vervolgonderzoek waarbij de wetenschappers pygmeeŽn volgden tijdens hun tochten door het regenwoud. "De kleinste leden van de stammen hoefden minder te bukken, zweetten minder en verbruikten daardoor minder energie", aldus Barreiro.

Door: NU.nl/Dennis Rijnvis

(nu.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

17-09-2014

'Evolutie maakte menselijke gezichten sterk verschillend'

Menselijke gezichten zijn waarschijnlijk geŽvolueerd om zo veel mogelijk uniek te zijn. Dat beweren Amerikaanse wetenschappers in een nieuwe studie.

Foto: 123RF

De verschillen tussen gezichten van individuen zijn bij mensen veel groter dan bij dieren.

Dat is waarschijnlijk in de loop van de evolutie zo gegroeid, omdat de herkenbaarheid van individuen van groot belang is bij sociale interacties tussen mensen.

Dat melden onderzoekers van de Universiteit van CaliforniŽ in het wetenschappelijk tijdschrift Nature Communications.

Genen

De wetenschappers analyseerden de DNA-volgorde van een groot aantal mensen over de hele wereld. Genen waarvan bekend is dat ze de vorm en bouw van het gezicht bepalen, bleken veel sterker te variŽren dan genen die het uiterlijk van andere lichaamsdelen beÔnvloeden.

Volgens hoofdonderzoeker Michael Sheenan suggereren de bevindingen dat het gezicht van mensen is geŽvolueerd om zo veel mogelijk uniek te zijn.

Waar de meeste dieren vooral op geuren afgaan om elkaar te herkennen, zijn sociale interacties bij mensen vooral visueel gericht.

Hersenen

"Mensen zijn fenomenaal goed in het herkennen van gezichten, er is zelfs een hersendeel gespecialiseerd in deze taak", verklaart Sheenan op nieuwssite ScienceDaily.

"Onze studie toont aan dat mensen in de loop van de evolutie zijn geslecteerd om uniek en herkenbaar te zijn."

Sheenan neemt zichzelf als voorbeeld om het bijzondere staaltje evolutie uit te leggen. "Het is duidelijk in mijn voordeel dat ik anderen gemakkelijk kan herkennen, maar het is ook handig dat ik herkenbaar ben voor anderen. Als het geen evolutionair voordeel zou zijn om een uniek gezicht te hebben, dan zouden we er allemaal ongeveer hetzelfde uitzien."

Door: NU.nl/Dennis Rijnvis

(nu.nl)

'Evolutie maakte menselijke gezichten sterk verschillend'

Menselijke gezichten zijn waarschijnlijk geŽvolueerd om zo veel mogelijk uniek te zijn. Dat beweren Amerikaanse wetenschappers in een nieuwe studie.

Foto: 123RF

De verschillen tussen gezichten van individuen zijn bij mensen veel groter dan bij dieren.

Dat is waarschijnlijk in de loop van de evolutie zo gegroeid, omdat de herkenbaarheid van individuen van groot belang is bij sociale interacties tussen mensen.

Dat melden onderzoekers van de Universiteit van CaliforniŽ in het wetenschappelijk tijdschrift Nature Communications.

Genen

De wetenschappers analyseerden de DNA-volgorde van een groot aantal mensen over de hele wereld. Genen waarvan bekend is dat ze de vorm en bouw van het gezicht bepalen, bleken veel sterker te variŽren dan genen die het uiterlijk van andere lichaamsdelen beÔnvloeden.

Volgens hoofdonderzoeker Michael Sheenan suggereren de bevindingen dat het gezicht van mensen is geŽvolueerd om zo veel mogelijk uniek te zijn.

Waar de meeste dieren vooral op geuren afgaan om elkaar te herkennen, zijn sociale interacties bij mensen vooral visueel gericht.

Hersenen

"Mensen zijn fenomenaal goed in het herkennen van gezichten, er is zelfs een hersendeel gespecialiseerd in deze taak", verklaart Sheenan op nieuwssite ScienceDaily.

"Onze studie toont aan dat mensen in de loop van de evolutie zijn geslecteerd om uniek en herkenbaar te zijn."

Sheenan neemt zichzelf als voorbeeld om het bijzondere staaltje evolutie uit te leggen. "Het is duidelijk in mijn voordeel dat ik anderen gemakkelijk kan herkennen, maar het is ook handig dat ik herkenbaar ben voor anderen. Als het geen evolutionair voordeel zou zijn om een uniek gezicht te hebben, dan zouden we er allemaal ongeveer hetzelfde uitzien."

Door: NU.nl/Dennis Rijnvis

(nu.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

03-10-2014

[ Er was eens... een eiwitpaar ]

Co-evolutieprincipe helpt bij opheldering 3D-eiwitstructuren

Als het oppervlak van een eiwit evolueert, moeten eiwitten die er interactie mee vertonen dezelfde kant op evolueren om te blijven ‘passen’. Dit ‘co-evolutieprincipe’ vergemakkelijkt het voorspellen van de 3D-structuur van eiwitparen aan de hand van hun aminozuursequenties, betogen Utrechtse en Amerikaanse onderzoekers in het onlinetijdschrift eLife.

Zo’n voorspelling is alleen mogelijk als je beschikt over voldoende sequenties die gelijkenis vertonen. Maar vaak is er geen andere eenvoudige manier om Łberhaupt een idee van zo’n eiwitinteractie te krijgen. Met enkel een aminozuursequentie en verder niets zijn de huidige modelleringsmethoden nog beperkt en kost het veel te veel rekenkracht om zo’n 3D-vorm te voorspellen. Analyse met rŲntgenkristallografie of kernspinresonantie (NMR) lukt ook alleen maar in gevallen dat het onderzochte eiwitcomplex wil uitkristalliseren of zich leent voor die NMR.

Volgens co-auteur Alexandre Bonvin (Universiteit Utrecht) hebben we van de paar honderdduizend eiwitinteracties binnen het menselijk lichaam dan ook nog maar een fractie in kaart. 'Ńlles wat je met bio-informatica kunt voorspellen heeft een toegevoegde waarde', zo vat hij het samen.

Bonvin en collegas van Harvard en het Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center baseerden hun aanpak op een database met alle eiwit-eiwitinteracties uit de bacterie E.coli waarvan de 3D-structuur al bekend is. Veel van die eiwit-eiwitinteracties zijn zoals dat heet ‘highly conserved’; je vindt ze in vrijwel ongewijzigde vorm terug in talloze andere soorten.'

Er werden computermodellen ontwikkeld die voorspellingen doen over hoe zo’n paar op elkaar past, welke aminozuren bij de eigenlijke binding betrokken zijn, en wat er, bij evolutie van het ene eiwit, aan het andere eiwit moet veranderen om de pasvorm te behouden (wat tevens verraadt welke aminozuren precies met elkaar in contact zijn).

Voor een set van 76 eiwitparen met zo'n beschikbare 3D-structuur waren voldoende variaties in aminozuursequenties bekend (hetzij bij E.coli, hetzij bij andere soorten) om iets te kunnen zeggen over het werkelijke verloop van de co-evolutie. Die subset werd gebruikt om de gedane voorspellingen te verifiŽren. In de meeste gevallen kwamen deze goed overeen met de daadwerkelijke contacten in de eitwitparen.

De onderzoekers denken nu dus een model in handen te hebben waarmee ze kunnen voorspellen hoe de interacties van andere eiwitparen, die behoren tot een bekende co-evolutionaire lijn, er in 3D uit zullen zien. De evolutiegegevens dienen daarbij als extra input voor de HADDOCK-modelleersoftware (High Ambiguity Driven protein-protein DOCKing), die eerder al aan de UU werd ontwikkeld.

Zo'n benadering heeft vooral grote voordelen als men kijkt naar membraaneiwitten en hun complexen, die experimenteel moeilijk te bestuderen zijn, voegt Bonvin er aan toe.

(c2w.nl)

[ Er was eens... een eiwitpaar ]

Co-evolutieprincipe helpt bij opheldering 3D-eiwitstructuren

Als het oppervlak van een eiwit evolueert, moeten eiwitten die er interactie mee vertonen dezelfde kant op evolueren om te blijven ‘passen’. Dit ‘co-evolutieprincipe’ vergemakkelijkt het voorspellen van de 3D-structuur van eiwitparen aan de hand van hun aminozuursequenties, betogen Utrechtse en Amerikaanse onderzoekers in het onlinetijdschrift eLife.

Zo’n voorspelling is alleen mogelijk als je beschikt over voldoende sequenties die gelijkenis vertonen. Maar vaak is er geen andere eenvoudige manier om Łberhaupt een idee van zo’n eiwitinteractie te krijgen. Met enkel een aminozuursequentie en verder niets zijn de huidige modelleringsmethoden nog beperkt en kost het veel te veel rekenkracht om zo’n 3D-vorm te voorspellen. Analyse met rŲntgenkristallografie of kernspinresonantie (NMR) lukt ook alleen maar in gevallen dat het onderzochte eiwitcomplex wil uitkristalliseren of zich leent voor die NMR.

Volgens co-auteur Alexandre Bonvin (Universiteit Utrecht) hebben we van de paar honderdduizend eiwitinteracties binnen het menselijk lichaam dan ook nog maar een fractie in kaart. 'Ńlles wat je met bio-informatica kunt voorspellen heeft een toegevoegde waarde', zo vat hij het samen.

Bonvin en collegas van Harvard en het Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center baseerden hun aanpak op een database met alle eiwit-eiwitinteracties uit de bacterie E.coli waarvan de 3D-structuur al bekend is. Veel van die eiwit-eiwitinteracties zijn zoals dat heet ‘highly conserved’; je vindt ze in vrijwel ongewijzigde vorm terug in talloze andere soorten.'

Er werden computermodellen ontwikkeld die voorspellingen doen over hoe zo’n paar op elkaar past, welke aminozuren bij de eigenlijke binding betrokken zijn, en wat er, bij evolutie van het ene eiwit, aan het andere eiwit moet veranderen om de pasvorm te behouden (wat tevens verraadt welke aminozuren precies met elkaar in contact zijn).

Voor een set van 76 eiwitparen met zo'n beschikbare 3D-structuur waren voldoende variaties in aminozuursequenties bekend (hetzij bij E.coli, hetzij bij andere soorten) om iets te kunnen zeggen over het werkelijke verloop van de co-evolutie. Die subset werd gebruikt om de gedane voorspellingen te verifiŽren. In de meeste gevallen kwamen deze goed overeen met de daadwerkelijke contacten in de eitwitparen.

De onderzoekers denken nu dus een model in handen te hebben waarmee ze kunnen voorspellen hoe de interacties van andere eiwitparen, die behoren tot een bekende co-evolutionaire lijn, er in 3D uit zullen zien. De evolutiegegevens dienen daarbij als extra input voor de HADDOCK-modelleersoftware (High Ambiguity Driven protein-protein DOCKing), die eerder al aan de UU werd ontwikkeld.

Zo'n benadering heeft vooral grote voordelen als men kijkt naar membraaneiwitten en hun complexen, die experimenteel moeilijk te bestuderen zijn, voegt Bonvin er aan toe.

(c2w.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

10-10-2014

Huidige evolutietheorie onder vuur?

Een groep evolutiebiologen stelt dat de evolutietheorie uitgebreid moet worden met vier concepten (embryonale ontwikkeling, plasticiteit, niche constructie en niet-genetische overerving). Aanhangers van het huidige evolutiemodel reageren gevat.

Er woedt een hevig debat onder evolutiebiologen. Sinds de Moderne Synthese in de jaren 30, waarin natuurlijke selectie, genetica, paleontologie en taxonomie verenigd werden, ligt de focus van evolutionair onderzoek op genen. Een groep evolutiebiologen stelt nu dat deze synthese uitgebreid moet worden met nieuwe concepten. Deze nieuwe synthese, Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) gedoopt, betoogt dat evolutie meer is dan enkel genen. In het vaktijdschrift Nature werden beide kampen tegenover elkaar gezet.

Vier concepten

Volgens de aanhangers van de nieuwe synthese ontbreken er vier concepten in de standaard evolutionaire theorie, namelijk embryonale ontwikkeling, plasticiteit, niche constructie en niet-genetische overerving. Deze concepten zijn weliswaar het onderwerp van talloze studies, ze worden echter gezien als uitkomsten van andere, meer fundamentele evolutionaire processen. De EES-verdedigers stellen dat deze vier concepten ook een belangrijke rol spelen als drijvende krachten in de evolutie. Plasticiteit (uiting van verschillende kenmerken afhankelijk van de omgeving) en bepaalde trends in de embryonale ontwikkeling kunnen bijvoorbeeld de eerste stap zijn in de oorsprong van nieuwe kenmerken. Niche constructie (de invloed van organismen op hun omgeving, zoals een beverdam) kan ervoor zorgen dat organismen zelf hun selectiedruk sturen. Tenslotte, niet-genetische processen, zoals epigenetica, kunnen het evolutionaire proces sterk beÔnvloeden.

Het antwoord

In het andere kamp reageert men dat de vier voorgestelde concepten reeds onderdeel uitmaken van diverse onderzoeksprogramma’s. Maar de basis van evolutiebiologie blijft nog steeds het gen. Het is zeker waar dat niet-genetische processen soms een rol spelen in de evolutie van bepaalde organismen, en plasticiteit in genexpressie is meermaals aangetoond. Maar om embryonale ontwikkeling of plasticiteit een fundamentele rol toe te bedelen, daarvoor is er voorlopig nog geen overtuigend bewijs.

Mijn visie

Als evolutiebioloog, wil ik ook graag mijn eigen visie op dit debat met de lezers delen. Ik neig ernaar me aan te sluiten bij het kamp dat de standaard evolutionaire theorie verdedigt. De vier concepten waarvan geopperd wordt dat zij ook een fundamentele rol spelen, zijn zeker de moeite waard om te bestuderen. Maar uiteindelijk kan alles teruggebracht worden op de genen. Bijvoorbeeld, plasticiteit is een gevolg van de expressie van verschillende genen, maar deze patronen in genexpressie worden weer gereguleerd door de andere genen. Het komt mij voor dat het EES-kamp niet zo zeer het huidige evolutiemodel aanvalt, maar eerder genetisch determinisme: de idee dat alles voorgeprogrammeerd is in het genoom en dat er bij gevolg geen vrije wil bestaat.

Jente Ottenburghs (1988) heeft sinds zijn Master Evolutie en Gedragsbiologie aan de Universiteit van Antwerpen een brede interesse voor evolutionaire biologie. Sinds mei 2012 werkt hij als PhD-student bij de Resource Ecology Group aan de Universiteit van Wageningen. Meer informatie over zijn onderzoek vindt u hier. En neem ook eens een kijkje op zijn blog waarop – hoe kan het ook anders – de evolutie eveneens centraal staat.

(scientias.nl)

Huidige evolutietheorie onder vuur?

Een groep evolutiebiologen stelt dat de evolutietheorie uitgebreid moet worden met vier concepten (embryonale ontwikkeling, plasticiteit, niche constructie en niet-genetische overerving). Aanhangers van het huidige evolutiemodel reageren gevat.

Er woedt een hevig debat onder evolutiebiologen. Sinds de Moderne Synthese in de jaren 30, waarin natuurlijke selectie, genetica, paleontologie en taxonomie verenigd werden, ligt de focus van evolutionair onderzoek op genen. Een groep evolutiebiologen stelt nu dat deze synthese uitgebreid moet worden met nieuwe concepten. Deze nieuwe synthese, Extended Evolutionary Synthesis (EES) gedoopt, betoogt dat evolutie meer is dan enkel genen. In het vaktijdschrift Nature werden beide kampen tegenover elkaar gezet.

Vier concepten

Volgens de aanhangers van de nieuwe synthese ontbreken er vier concepten in de standaard evolutionaire theorie, namelijk embryonale ontwikkeling, plasticiteit, niche constructie en niet-genetische overerving. Deze concepten zijn weliswaar het onderwerp van talloze studies, ze worden echter gezien als uitkomsten van andere, meer fundamentele evolutionaire processen. De EES-verdedigers stellen dat deze vier concepten ook een belangrijke rol spelen als drijvende krachten in de evolutie. Plasticiteit (uiting van verschillende kenmerken afhankelijk van de omgeving) en bepaalde trends in de embryonale ontwikkeling kunnen bijvoorbeeld de eerste stap zijn in de oorsprong van nieuwe kenmerken. Niche constructie (de invloed van organismen op hun omgeving, zoals een beverdam) kan ervoor zorgen dat organismen zelf hun selectiedruk sturen. Tenslotte, niet-genetische processen, zoals epigenetica, kunnen het evolutionaire proces sterk beÔnvloeden.

Het antwoord

In het andere kamp reageert men dat de vier voorgestelde concepten reeds onderdeel uitmaken van diverse onderzoeksprogramma’s. Maar de basis van evolutiebiologie blijft nog steeds het gen. Het is zeker waar dat niet-genetische processen soms een rol spelen in de evolutie van bepaalde organismen, en plasticiteit in genexpressie is meermaals aangetoond. Maar om embryonale ontwikkeling of plasticiteit een fundamentele rol toe te bedelen, daarvoor is er voorlopig nog geen overtuigend bewijs.

Mijn visie

Als evolutiebioloog, wil ik ook graag mijn eigen visie op dit debat met de lezers delen. Ik neig ernaar me aan te sluiten bij het kamp dat de standaard evolutionaire theorie verdedigt. De vier concepten waarvan geopperd wordt dat zij ook een fundamentele rol spelen, zijn zeker de moeite waard om te bestuderen. Maar uiteindelijk kan alles teruggebracht worden op de genen. Bijvoorbeeld, plasticiteit is een gevolg van de expressie van verschillende genen, maar deze patronen in genexpressie worden weer gereguleerd door de andere genen. Het komt mij voor dat het EES-kamp niet zo zeer het huidige evolutiemodel aanvalt, maar eerder genetisch determinisme: de idee dat alles voorgeprogrammeerd is in het genoom en dat er bij gevolg geen vrije wil bestaat.

Jente Ottenburghs (1988) heeft sinds zijn Master Evolutie en Gedragsbiologie aan de Universiteit van Antwerpen een brede interesse voor evolutionaire biologie. Sinds mei 2012 werkt hij als PhD-student bij de Resource Ecology Group aan de Universiteit van Wageningen. Meer informatie over zijn onderzoek vindt u hier. En neem ook eens een kijkje op zijn blog waarop – hoe kan het ook anders – de evolutie eveneens centraal staat.

(scientias.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

16-10-2014

Evolutie van het vliegen vooral gestuurd door wendbaarheid

De evolutie van het vliegen lijkt vooral gedreven te zijn door de noodzaak voor stabiliteit bij het zweven.

Foto: AFP

Dat schrijft een interdisciplinair team van biologen en technici donderdag in Peer J.

Het team onderzocht de evolutie van vliegen door modellen van huidige en uitgestorven dieren te maken, en die te testen in een windtunnel.

Ze maakten vier bestaande vogels, zeven oervogelachtigen en twee vleermuizen, en als controle een windvaan en een bol. De modellen werden onder verschillende hoeken in de tunnel geplaatst, waarna sensoren de verschillende krachten maten.

Veren

Uit de windtunneltests bleek dat de veren op voor- en achterpoten en de staart van pre-vogel dinosaurussen konden helpen bij het manoeuvreren in de lucht. Bij het verder evolueren werden de veren op staart en achterpoten kleiner, en groeiden juist de voorpoten.

De studie laat door de vergelijking van verschillende vliegende dieren zien dat veel structuren waarvan gedacht werd dat ze gebruikt werden voor de aandrijving, eigenlijk voor stabiliteit waren. Kracht zetten bij het vliegen zou dan dus een nieuwere eigenschap zijn.

Door: NU.nl/Stephan van Duin

(nu.nl)

Evolutie van het vliegen vooral gestuurd door wendbaarheid

De evolutie van het vliegen lijkt vooral gedreven te zijn door de noodzaak voor stabiliteit bij het zweven.

Foto: AFP

Dat schrijft een interdisciplinair team van biologen en technici donderdag in Peer J.

Het team onderzocht de evolutie van vliegen door modellen van huidige en uitgestorven dieren te maken, en die te testen in een windtunnel.

Ze maakten vier bestaande vogels, zeven oervogelachtigen en twee vleermuizen, en als controle een windvaan en een bol. De modellen werden onder verschillende hoeken in de tunnel geplaatst, waarna sensoren de verschillende krachten maten.

Veren

Uit de windtunneltests bleek dat de veren op voor- en achterpoten en de staart van pre-vogel dinosaurussen konden helpen bij het manoeuvreren in de lucht. Bij het verder evolueren werden de veren op staart en achterpoten kleiner, en groeiden juist de voorpoten.

De studie laat door de vergelijking van verschillende vliegende dieren zien dat veel structuren waarvan gedacht werd dat ze gebruikt werden voor de aandrijving, eigenlijk voor stabiliteit waren. Kracht zetten bij het vliegen zou dan dus een nieuwere eigenschap zijn.

Door: NU.nl/Stephan van Duin

(nu.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

21-10-2014

Is evolutie voorspelbaar? Soms wel, zo blijkt!

Onderzoekers vragen zich al lang af of evolutie een voorspelbaar proces is. Nieuw onderzoek onder inktvissen suggereert nu dat de evolutie van complexe organen in deze organismen – achteraf gezien – heel voorspelbaar is verlopen.

De onderzoekers bestudeerden twee soorten inktvissen: Euprymna scolopes (onder meer te vinden voor de kust van Hawaii) en Uroteuthis edulis (een Japanse inktvis die ook vaak in sushi-restaurants op het menu staat, zie de afbeelding hierboven). De twee soorten zijn heel in de verte nog aan elkaar verwant. Bovendien beschikken ze allebei over lichtgevende organen. Die organen geven licht, omdat ze bepaalde lichtgevende bacteriŽn bevatten. De inktvissen kunnen zelf regelen hoeveel licht hun lichtgevende organen geven.

LICHTGEVENDE ORGANEN

Waarom hebben inktvissen eigenlijk lichtgevende organen? Onderzoek suggereert dat de organen van pas komen als de inktvis behoefte heeft aan camouflage. “Als je je voorstelt dat je op je rug diep in de oceaan ligt en naar boven kijkt, zie je dat al het licht recht van boven komt,” legt onderzoeker Todd Oakley uit. “Er zijn geen muren of bomen die het licht reflecteren, dus als er iets boven je zit, werpt dat een schaduw. De inktvis kan licht produceren dat overeenkomt met het licht achter hem, zodat deze geen schaduw werpt en dat is een soort van camouflage.”

De genetische basis

De onderzoekers waren geÔnteresseerd in de genen die aan deze lichtgevende organen ten grondslag lagen. Ze vroegen zich af in hoeverre de genetische basis voor deze lichtgevende organen – die de twee inktvissoorten onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkeld hebben – vergelijkbaar is. Om dat te achterhalen, brachten ze alle genen die tot uiting komen in deze organen, in kaart.

De resultaten

De resultaten zijn opmerkelijk. De genetische basis voor de lichtgevende organen in E. scolopes bleek opvallend sterk te lijken op de genen die in U. edulis aan de lichtgevende organen ten grondslag lagen. “Normaal gesproken zouden we, wanneer twee complexe organen zich onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkelen, verwachten dat ze elk heel verschillende evolutionaire paden bewandelen om terecht te komen waar ze vandaag de dag zijn,” vertelt onderzoeker Todd Oakley. “De onverwachte overeenkomsten laten zien dat deze twee inktvissen heel vergelijkbare paden bewandelden om deze eigenschappen te ontwikkelen.”

De onderzoekers demonstreren dat inktvissen gedurende hun evolutie herhaaldelijk lichtgevende organen ontwikkelden en dat de genetische bases voor die lichtgevende organen elke keer veel op elkaar leken. Het suggereert dat de evolutie van de totale genexpressie die aan convergente – door soorten onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkelde – complexe eigenschappen ten grondslag ligt, voorspelbaar is.

(scientias.nl)

Is evolutie voorspelbaar? Soms wel, zo blijkt!

Onderzoekers vragen zich al lang af of evolutie een voorspelbaar proces is. Nieuw onderzoek onder inktvissen suggereert nu dat de evolutie van complexe organen in deze organismen – achteraf gezien – heel voorspelbaar is verlopen.

De onderzoekers bestudeerden twee soorten inktvissen: Euprymna scolopes (onder meer te vinden voor de kust van Hawaii) en Uroteuthis edulis (een Japanse inktvis die ook vaak in sushi-restaurants op het menu staat, zie de afbeelding hierboven). De twee soorten zijn heel in de verte nog aan elkaar verwant. Bovendien beschikken ze allebei over lichtgevende organen. Die organen geven licht, omdat ze bepaalde lichtgevende bacteriŽn bevatten. De inktvissen kunnen zelf regelen hoeveel licht hun lichtgevende organen geven.

LICHTGEVENDE ORGANEN

Waarom hebben inktvissen eigenlijk lichtgevende organen? Onderzoek suggereert dat de organen van pas komen als de inktvis behoefte heeft aan camouflage. “Als je je voorstelt dat je op je rug diep in de oceaan ligt en naar boven kijkt, zie je dat al het licht recht van boven komt,” legt onderzoeker Todd Oakley uit. “Er zijn geen muren of bomen die het licht reflecteren, dus als er iets boven je zit, werpt dat een schaduw. De inktvis kan licht produceren dat overeenkomt met het licht achter hem, zodat deze geen schaduw werpt en dat is een soort van camouflage.”

De genetische basis

De onderzoekers waren geÔnteresseerd in de genen die aan deze lichtgevende organen ten grondslag lagen. Ze vroegen zich af in hoeverre de genetische basis voor deze lichtgevende organen – die de twee inktvissoorten onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkeld hebben – vergelijkbaar is. Om dat te achterhalen, brachten ze alle genen die tot uiting komen in deze organen, in kaart.

De resultaten

De resultaten zijn opmerkelijk. De genetische basis voor de lichtgevende organen in E. scolopes bleek opvallend sterk te lijken op de genen die in U. edulis aan de lichtgevende organen ten grondslag lagen. “Normaal gesproken zouden we, wanneer twee complexe organen zich onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkelen, verwachten dat ze elk heel verschillende evolutionaire paden bewandelen om terecht te komen waar ze vandaag de dag zijn,” vertelt onderzoeker Todd Oakley. “De onverwachte overeenkomsten laten zien dat deze twee inktvissen heel vergelijkbare paden bewandelden om deze eigenschappen te ontwikkelen.”

De onderzoekers demonstreren dat inktvissen gedurende hun evolutie herhaaldelijk lichtgevende organen ontwikkelden en dat de genetische bases voor die lichtgevende organen elke keer veel op elkaar leken. Het suggereert dat de evolutie van de totale genexpressie die aan convergente – door soorten onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkelde – complexe eigenschappen ten grondslag ligt, voorspelbaar is.

(scientias.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

23-10-2014

Oudste menselijke genoom bevat Neanderthaler-DNA

Wetenschappers hebben het genoom van een 45.000-jaar oude mens in kaart gebracht om te ontrafelen wanneer Neanderthalers en moderne mensen seks hadden. Zij concluderen dat de vermenging van DNA zo’n 50.000 tot 60.000 jaar geleden plaatsvond.

In 2008 werd het dijbeen van een man gevonden langs de rivier Irtysh in het westen van SiberiŽ. Deze man leefde 45.000 jaar geleden. Het is tot op het heden de oudste moderne mens waarvan het genoom is ontrafeld. “Het is daarnaast ťťn van de oudste mensen die ooit buiten Afrika of het Midden-Oosten is gevonden”, concludeert antropoloog Bence Viola.

Vroege vermenging

De onderzoekers beweren dat de desbetreffende man Neanderthaler-DNA heeft. Sterker nog, de

hoeveelheid Neanderthaler-DNA is vergelijkbaar met het percentage in mensen die vandaag de dag op aarde leven. De gemiddelde Nederlander of Belg heeft 1,5 tot 2,1 procent Neanderthaler-DNA in zijn lichaam. Omdat dit percentage 45.000 jaar geleden niet anders was, concluderen wetenschappers dat de vermenging van DNA zeker 7.000 tot 13.000 jaar daarvoor plaatsvond. Dit betekent dat moderne mensen en Neanderthalers 50.000 tot 60.000 jaar geleden seks hadden, kort nadat mensen zich vanuit Afrika en het Midden-Oosten over de aarde verspreidden.

Menu

Het dijbeen onthulde overigens nog meer geheimen. Zo at deze man voornamelijk planten en groenten, zoals knoflook, aubergines, peren, bonen en tarwe. Dit is af te leiden uit koolstof- en stikstofisotopen in het dijbeen. Daarnaast had de man zoetwatervissen en dieren op het menu staan.

Mutaties

Omdat het 45.000 jaar oude genoom van extreem goede kwaliteit is, hebben wetenschappers het aantal mutaties kunnen berekenen. Hieruit blijkt dat er ongeveer ťťn tot twee mutaties per jaar plaatsvinden in de genomen van mensen in Europa en AziŽ. Dit komt overeen met andere onderzoeken naar de genetische verschillen tussen ouders en kinderen.

(scientias.nl)

Oudste menselijke genoom bevat Neanderthaler-DNA

Wetenschappers hebben het genoom van een 45.000-jaar oude mens in kaart gebracht om te ontrafelen wanneer Neanderthalers en moderne mensen seks hadden. Zij concluderen dat de vermenging van DNA zo’n 50.000 tot 60.000 jaar geleden plaatsvond.

In 2008 werd het dijbeen van een man gevonden langs de rivier Irtysh in het westen van SiberiŽ. Deze man leefde 45.000 jaar geleden. Het is tot op het heden de oudste moderne mens waarvan het genoom is ontrafeld. “Het is daarnaast ťťn van de oudste mensen die ooit buiten Afrika of het Midden-Oosten is gevonden”, concludeert antropoloog Bence Viola.

Vroege vermenging

De onderzoekers beweren dat de desbetreffende man Neanderthaler-DNA heeft. Sterker nog, de

hoeveelheid Neanderthaler-DNA is vergelijkbaar met het percentage in mensen die vandaag de dag op aarde leven. De gemiddelde Nederlander of Belg heeft 1,5 tot 2,1 procent Neanderthaler-DNA in zijn lichaam. Omdat dit percentage 45.000 jaar geleden niet anders was, concluderen wetenschappers dat de vermenging van DNA zeker 7.000 tot 13.000 jaar daarvoor plaatsvond. Dit betekent dat moderne mensen en Neanderthalers 50.000 tot 60.000 jaar geleden seks hadden, kort nadat mensen zich vanuit Afrika en het Midden-Oosten over de aarde verspreidden.

Menu

Het dijbeen onthulde overigens nog meer geheimen. Zo at deze man voornamelijk planten en groenten, zoals knoflook, aubergines, peren, bonen en tarwe. Dit is af te leiden uit koolstof- en stikstofisotopen in het dijbeen. Daarnaast had de man zoetwatervissen en dieren op het menu staan.

Mutaties

Omdat het 45.000 jaar oude genoom van extreem goede kwaliteit is, hebben wetenschappers het aantal mutaties kunnen berekenen. Hieruit blijkt dat er ongeveer ťťn tot twee mutaties per jaar plaatsvinden in de genomen van mensen in Europa en AziŽ. Dit komt overeen met andere onderzoeken naar de genetische verschillen tussen ouders en kinderen.

(scientias.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

Nounounou. Op basis van dit bericht vind ik de conclusie in de laatste alinea ongelooflijke onzin!quote:Op donderdag 23 oktober 2014 10:33 schreef ExperimentalFrentalMental het volgende:

21-10-2014

Is evolutie voorspelbaar? Soms wel, zo blijkt!

[ afbeelding ]

Onderzoekers vragen zich al lang af of evolutie een voorspelbaar proces is. Nieuw onderzoek onder inktvissen suggereert nu dat de evolutie van complexe organen in deze organismen – achteraf gezien – heel voorspelbaar is verlopen.

De onderzoekers bestudeerden twee soorten inktvissen: Euprymna scolopes (onder meer te vinden voor de kust van Hawaii) en Uroteuthis edulis (een Japanse inktvis die ook vaak in sushi-restaurants op het menu staat, zie de afbeelding hierboven). De twee soorten zijn heel in de verte nog aan elkaar verwant. Bovendien beschikken ze allebei over lichtgevende organen. Die organen geven licht, omdat ze bepaalde lichtgevende bacteriŽn bevatten. De inktvissen kunnen zelf regelen hoeveel licht hun lichtgevende organen geven.

LICHTGEVENDE ORGANEN

Waarom hebben inktvissen eigenlijk lichtgevende organen? Onderzoek suggereert dat de organen van pas komen als de inktvis behoefte heeft aan camouflage. “Als je je voorstelt dat je op je rug diep in de oceaan ligt en naar boven kijkt, zie je dat al het licht recht van boven komt,” legt onderzoeker Todd Oakley uit. “Er zijn geen muren of bomen die het licht reflecteren, dus als er iets boven je zit, werpt dat een schaduw. De inktvis kan licht produceren dat overeenkomt met het licht achter hem, zodat deze geen schaduw werpt en dat is een soort van camouflage.”

De genetische basis

De onderzoekers waren geÔnteresseerd in de genen die aan deze lichtgevende organen ten grondslag lagen. Ze vroegen zich af in hoeverre de genetische basis voor deze lichtgevende organen – die de twee inktvissoorten onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkeld hebben – vergelijkbaar is. Om dat te achterhalen, brachten ze alle genen die tot uiting komen in deze organen, in kaart.

De resultaten

De resultaten zijn opmerkelijk. De genetische basis voor de lichtgevende organen in E. scolopes bleek opvallend sterk te lijken op de genen die in U. edulis aan de lichtgevende organen ten grondslag lagen. “Normaal gesproken zouden we, wanneer twee complexe organen zich onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkelen, verwachten dat ze elk heel verschillende evolutionaire paden bewandelen om terecht te komen waar ze vandaag de dag zijn,” vertelt onderzoeker Todd Oakley. “De onverwachte overeenkomsten laten zien dat deze twee inktvissen heel vergelijkbare paden bewandelden om deze eigenschappen te ontwikkelen.”

De onderzoekers demonstreren dat inktvissen gedurende hun evolutie herhaaldelijk lichtgevende organen ontwikkelden en dat de genetische bases voor die lichtgevende organen elke keer veel op elkaar leken. Het suggereert dat de evolutie van de totale genexpressie die aan convergente – door soorten onafhankelijk van elkaar ontwikkelde – complexe eigenschappen ten grondslag ligt, voorspelbaar is.

(scientias.nl)

Onderschat nooit de kracht van domme mensen in grote groepen!

Der Irrsinn ist bei Einzelnen etwas Seltenes - aber bei Gruppen, Parteien, VŲlkern, Zeiten die Regel. (Friedrich Nietzsche)

Der Irrsinn ist bei Einzelnen etwas Seltenes - aber bei Gruppen, Parteien, VŲlkern, Zeiten die Regel. (Friedrich Nietzsche)

Misschien dat de conclusie zinniger klinkt in de originele wetenschappelijke taal? Of een beetje onhandig vertaald uit het Engels?quote:Op vrijdag 24 oktober 2014 00:31 schreef Kees22 het volgende:

[..]

Nounounou. Op basis van dit bericht vind ik de conclusie in de laatste alinea ongelooflijke onzin!

Free Assange! Hack the Planet

[b]Op dinsdag 6 januari 2009 19:59 schreef Papierversnipperaar het volgende:[/b]

De gevolgen van de argumenten van de anti-rook maffia

[b]Op dinsdag 6 januari 2009 19:59 schreef Papierversnipperaar het volgende:[/b]

De gevolgen van de argumenten van de anti-rook maffia

24-10-2014

Hagedis in Florida evolueert in krap vijftien jaar tijd

Evolutie: een traag proces? Niet in Florida! Daar zijn hagedissen in reactie op de komst van een indringer in krap vijftien jaar tijd (oftewel twintig generaties) geŽvolueerd. Hun tenen zijn nu groter, waardoor ze hoger kunnen klimmen.

De roodkeelanolis komt van oorsprong in het zuidoosten van de VS voor. Maar in de jaren vijftig kreeg de hagedis concurrentie. De Sagra’s anolis – die van oorsprong op Cuba en de Bahama’s voorkomt – dook op in Florida. Waarschijnlijk was de hagedis samen met landbouwproducten vanuit Cuba naar de VS komen zetten. En daar beviel het de Sagra’s anolis wel: in rap tempo verspreidden de hagedissen zich over het zuidoostelijke deel van de VS.

Verandering

Wetenschappers hebben nu ontdekt dat de roodkeelanolis in korte tijd – waarschijnlijk in reactie op de komst van Sagra’s anolis – sterk veranderd is. Binnen enkele maanden na de komst van de Cubaanse hagedissen verhuisden de hagedissen die van oorsprong in het zuidoosten van de VS voorkwamen naar een hoger leefgebied: ze klommen hoger in bomen. En in een periode van vijftien jaar (twintig generaties) werden hun tenen groter. Grotere tenen betekent dat de hagedissen meer grip hebben en dus beter in staat zijn om te klimmen.

Heel snel

“We hadden wel voorspeld dat we een verandering zouden zien,” vertelt onderzoeker Yoel Stuart. “Maar de mate en snelheid waarmee ze evolueren is verrassend. Om het in het juiste perspectief te plaatsen: als de lengte van mensen zo snel veranderde als de tenen van deze hagedissen, dan zou de lengte van de gemiddelde Amerikaan van 1.75 meter in twintig generaties tijd toenemen tot 1.93 meter. Hoewel mensen langer leven dan hagedissen, zou dit in evolutionaire termen een heel snelle verandering zijn.”

De onderzoekers gaan ervan uit dat de verandering die ze bij de roodkeelanolis zien, het gevolg is van de competitie met Sagra’s anolis die in hetzelfde gebied leeft en op hetzelfde voedsel jaagt. De onderzoekers wijzen er bovendien op dat de volwassen roodkeelanolissen en Sagra’s anolissen de jongen van de andere soort eten. “Dus misschien is het wel zo dat je wanneer je een jonge hagedis bent snel hoger in de bomen moet klimmen om te voorkomen dat je wordt opgegeten. Misschien gaat dat beter als je grotere tenen hebt.

(scientias.nl)

Hagedis in Florida evolueert in krap vijftien jaar tijd

Evolutie: een traag proces? Niet in Florida! Daar zijn hagedissen in reactie op de komst van een indringer in krap vijftien jaar tijd (oftewel twintig generaties) geŽvolueerd. Hun tenen zijn nu groter, waardoor ze hoger kunnen klimmen.

De roodkeelanolis komt van oorsprong in het zuidoosten van de VS voor. Maar in de jaren vijftig kreeg de hagedis concurrentie. De Sagra’s anolis – die van oorsprong op Cuba en de Bahama’s voorkomt – dook op in Florida. Waarschijnlijk was de hagedis samen met landbouwproducten vanuit Cuba naar de VS komen zetten. En daar beviel het de Sagra’s anolis wel: in rap tempo verspreidden de hagedissen zich over het zuidoostelijke deel van de VS.

Verandering

Wetenschappers hebben nu ontdekt dat de roodkeelanolis in korte tijd – waarschijnlijk in reactie op de komst van Sagra’s anolis – sterk veranderd is. Binnen enkele maanden na de komst van de Cubaanse hagedissen verhuisden de hagedissen die van oorsprong in het zuidoosten van de VS voorkwamen naar een hoger leefgebied: ze klommen hoger in bomen. En in een periode van vijftien jaar (twintig generaties) werden hun tenen groter. Grotere tenen betekent dat de hagedissen meer grip hebben en dus beter in staat zijn om te klimmen.

Heel snel

“We hadden wel voorspeld dat we een verandering zouden zien,” vertelt onderzoeker Yoel Stuart. “Maar de mate en snelheid waarmee ze evolueren is verrassend. Om het in het juiste perspectief te plaatsen: als de lengte van mensen zo snel veranderde als de tenen van deze hagedissen, dan zou de lengte van de gemiddelde Amerikaan van 1.75 meter in twintig generaties tijd toenemen tot 1.93 meter. Hoewel mensen langer leven dan hagedissen, zou dit in evolutionaire termen een heel snelle verandering zijn.”

De onderzoekers gaan ervan uit dat de verandering die ze bij de roodkeelanolis zien, het gevolg is van de competitie met Sagra’s anolis die in hetzelfde gebied leeft en op hetzelfde voedsel jaagt. De onderzoekers wijzen er bovendien op dat de volwassen roodkeelanolissen en Sagra’s anolissen de jongen van de andere soort eten. “Dus misschien is het wel zo dat je wanneer je een jonge hagedis bent snel hoger in de bomen moet klimmen om te voorkomen dat je wordt opgegeten. Misschien gaat dat beter als je grotere tenen hebt.

(scientias.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

Ik bedoel de conclusie dat de evolutie van genexpressie voorspelbaar is.quote:Op zondag 26 oktober 2014 11:33 schreef Papierversnipperaar het volgende:

[..]

Misschien dat de conclusie zinniger klinkt in de originele wetenschappelijke taal? Of een beetje onhandig vertaald uit het Engels?

Verder:

Twee soorten inktvis die tot een soortgelijke camouflage komen? Och, dat is toch niet zo bijzonder?

Onderschat nooit de kracht van domme mensen in grote groepen!

Der Irrsinn ist bei Einzelnen etwas Seltenes - aber bei Gruppen, Parteien, VŲlkern, Zeiten die Regel. (Friedrich Nietzsche)

Der Irrsinn ist bei Einzelnen etwas Seltenes - aber bei Gruppen, Parteien, VŲlkern, Zeiten die Regel. (Friedrich Nietzsche)

05-11-2014

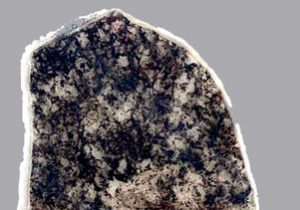

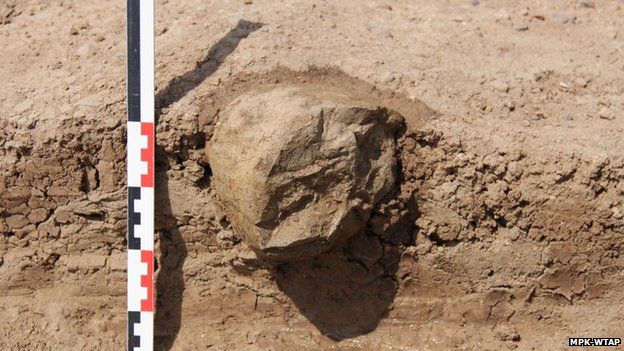

Nieuw fossiel blijkt een belangrijke ‘missing link’ te zijn

Wetenschappers hebben het fossiel van een 250 miljoen jaar oude zeereptiel gevonden, die de voorouder is van de ichthyosauriŽrs. De oorsprong van de ichthyosauriŽrs was een lange tijd ťťn van de raadsels binnen de paleontologie. Het fossiel is dus een belangrijke missing link.

De kleine zeereptiel heeft de naam ‘Cartorhynchus lenticarpus’ gekregen en was slechts 0,4 meter lang. Het dier leefde niet alleen op het land, maar kon ook in de zee leven. De Cartorhynchus lenticarpus was ťťn van de eerste roofdieren na de Perm-Trias-massa-extinctie en verorberde inktvissen, garnalen en meer soortgelijke zeediertjes.

Het 250 miljoen jaar oude fossiel in beeld.

“VEEL CREATIONISTEN ZIEN DE ICHTHYOSAURIňR ALS H…T BEWIJS DAT DE EVOLUTIETHEORIE NIET KLOPT”

De grootste extinctie ooit

De Perm-Trias-massa-extinctie was de grootste extinctie ooit. Vergeleken hierbij was de Krijt-Tertiair-massa-extinctie van 65 miljoen jaar geleden, waarbij de dinosauriŽrs het loodje legden, maar een kleine gebeurtenis. Tijdens de Perm-Trias-massa-extinctie stierf 95% van alle in zee levende soorten en 70% van de gewervelde landdieren. Daarnaast verdween ťťn derde van alle insectsoorten. Dit kwam omdat de aarde opwarmde, de oceanen verzuurden er een zuurstofgebrek in de oceanen ontstond.

Maak kennis met de ichthyosauriŽr! Vindt jij dit uitgestorven zeedier ook op een dolfijn lijken?

IchthyosauriŽrs

De ichthyosauriŽrs waren zeedieren, die 250 miljoen jaar geleden verschenen. “Veel creationisten zien de ichthyosauriŽr als hťt bewijs dat de evolutietheorie niet klopt”, vertelt hoofdauteur Ryosuke Motani van de universiteit van CaliforniŽ aan de Washington Post. “IchthyosauriŽrs hebben de botstructuur van een reptiel, dus dat betekent dat hun voorouders ooit op het land leefden. Toch waren ichthyosauriŽrs volledig aangepast aan leven in het water. De link konden we lange tijd niet vinden.”

Moeilijke puzzel

Wetenschappers melden in een paper in het wetenschappelijke journaal Nature dat de Cartorhynchus lenticarpus deze missing link is. Het fossiel werd al in 2011 gevonden, maar het was een lastige puzzel om in elkaar te leggen. “Ik zag al snel dat het dier familie was van de ichthyosauriŽr, maar ik kon hem niet precies plaatsen”, onthult Motani. “Pas na een jaar wist ik het zeker: dit is de voorouder van de ichthyosauriŽr.”

Verschillen

Het dier verschilt wel iets van de ichthyosauriŽr. De ichthyosauriŽr had een lange snuit om vissen te vangen. De snuit van de Cartorhynchus lenticarpus is korter en lijkt meer op die van een landreptiel. Daarnaast had de Cartorhynchus lenticarpus grote vinnen en flexibele polsen om op het land te kunnen wandelen, net zoals zeehonden dat doen. Verder had de zeereptiel zwaardere en dikkere botten dan de ichthyosauriŽr.

(scientist.nl)

Nieuw fossiel blijkt een belangrijke ‘missing link’ te zijn

Wetenschappers hebben het fossiel van een 250 miljoen jaar oude zeereptiel gevonden, die de voorouder is van de ichthyosauriŽrs. De oorsprong van de ichthyosauriŽrs was een lange tijd ťťn van de raadsels binnen de paleontologie. Het fossiel is dus een belangrijke missing link.

De kleine zeereptiel heeft de naam ‘Cartorhynchus lenticarpus’ gekregen en was slechts 0,4 meter lang. Het dier leefde niet alleen op het land, maar kon ook in de zee leven. De Cartorhynchus lenticarpus was ťťn van de eerste roofdieren na de Perm-Trias-massa-extinctie en verorberde inktvissen, garnalen en meer soortgelijke zeediertjes.

Het 250 miljoen jaar oude fossiel in beeld.

“VEEL CREATIONISTEN ZIEN DE ICHTHYOSAURIňR ALS H…T BEWIJS DAT DE EVOLUTIETHEORIE NIET KLOPT”

De grootste extinctie ooit

De Perm-Trias-massa-extinctie was de grootste extinctie ooit. Vergeleken hierbij was de Krijt-Tertiair-massa-extinctie van 65 miljoen jaar geleden, waarbij de dinosauriŽrs het loodje legden, maar een kleine gebeurtenis. Tijdens de Perm-Trias-massa-extinctie stierf 95% van alle in zee levende soorten en 70% van de gewervelde landdieren. Daarnaast verdween ťťn derde van alle insectsoorten. Dit kwam omdat de aarde opwarmde, de oceanen verzuurden er een zuurstofgebrek in de oceanen ontstond.

Maak kennis met de ichthyosauriŽr! Vindt jij dit uitgestorven zeedier ook op een dolfijn lijken?

IchthyosauriŽrs

De ichthyosauriŽrs waren zeedieren, die 250 miljoen jaar geleden verschenen. “Veel creationisten zien de ichthyosauriŽr als hťt bewijs dat de evolutietheorie niet klopt”, vertelt hoofdauteur Ryosuke Motani van de universiteit van CaliforniŽ aan de Washington Post. “IchthyosauriŽrs hebben de botstructuur van een reptiel, dus dat betekent dat hun voorouders ooit op het land leefden. Toch waren ichthyosauriŽrs volledig aangepast aan leven in het water. De link konden we lange tijd niet vinden.”

Moeilijke puzzel

Wetenschappers melden in een paper in het wetenschappelijke journaal Nature dat de Cartorhynchus lenticarpus deze missing link is. Het fossiel werd al in 2011 gevonden, maar het was een lastige puzzel om in elkaar te leggen. “Ik zag al snel dat het dier familie was van de ichthyosauriŽr, maar ik kon hem niet precies plaatsen”, onthult Motani. “Pas na een jaar wist ik het zeker: dit is de voorouder van de ichthyosauriŽr.”

Verschillen

Het dier verschilt wel iets van de ichthyosauriŽr. De ichthyosauriŽr had een lange snuit om vissen te vangen. De snuit van de Cartorhynchus lenticarpus is korter en lijkt meer op die van een landreptiel. Daarnaast had de Cartorhynchus lenticarpus grote vinnen en flexibele polsen om op het land te kunnen wandelen, net zoals zeehonden dat doen. Verder had de zeereptiel zwaardere en dikkere botten dan de ichthyosauriŽr.

(scientist.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

Lekker zinloze toevoeging aan een dergelijk artikel. Dat creationisten wat cherrypicken in het fossielenbestand lijkt me niet zo relevant.quote:“VEEL CREATIONISTEN ZIEN DE ICHTHYOSAURIňR ALS H…T BEWIJS DAT DE EVOLUTIETHEORIE NIET KLOPT”

Volkorenbrood: "Geen quotes meer in jullie sigs gaarne."

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/11/141106113334.htm

From single cells to multicellular life: Researchers capture the emergence of multicellular life in real-time experiments

All multicellular creatures are descended from single-celled organisms. The leap from unicellularity to multicellularity is possible only if the originally independent cells collaborate. So-called cheating cells that exploit the cooperation of others are considered a major obstacle. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in PlŲn, Germany, together with researchers from New Zealand and the USA, have observed in real time the evolution of simple self-reproducing groups of cells from previously individual cells. The nascent organisms are comprised of a single tissue dedicated to acquiring oxygen, but this tissue also generates cells that are the seeds of future generations: a reproductive division of labour. Intriguingly, the cells that serve as a germ line were derived from cheating cells whose destructive effects were tamed by integration into a life cycle that allowed groups to reproduce. The life cycle turned out to be a spectacular gift to evolution. Rather than working directly on cells, evolution was able to work on a developmental programme that eventually merged cells into a single organism. When this happened groups began to prosper with the once free-living cells coming to work for the good of the whole.

Single bacterial cells of Pseudomonas fluorescens usually live independently of each other. However, some mutations allow cells to produce adhesive glues that cause cells to remain stuck together after cell division. Under appropriate ecological conditions, the cellular assemblies can be favoured by natural selection, despite a cost to individual cells that produce the glues. When Pseudomonas fluorescens is grown in unshaken test tubes the cellular collectives prosper because they form mats at the surface of liquids where the cells gain access to oxygen that is otherwise -- in the liquid -- unavailable.

Given both costs associated with production of adhesive substances and benefits that accrue to the collective, natural selection is expected to favour types that no longer produce costly glues, but take advantage of the mat to support their own rapid growth. Such types are often referred to as cheats because they take advantage of the community effort while paying none of the costs. Cheats arise in the authors' experimental populations and bring about collapse of the mats. The mats fail when cheats prosper: cheats obtain an abundance of oxygen, but contribute no glue to keep the mat from disintegrating -- the mats eventually break and fall to the bottom where they are starved of oxygen.

Paul Rainey, who led the study at the New Zealand Institute for Advanced Study and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology, explains: "Simple cooperating groups -- like the mats that interest us -- stand as one possible origin of multicellular life, but no sooner do the mats arise, than they fail: the same process that ensures their success -- natural selection -- , ensures their demise." But even more problematic is that groups, once extant, must have some means of reproducing themselves, else they are of little evolutionary consequence.

Pondering this problem led Rainey to an ingenious solution. What if cheats could act as seeds -- a germ line -- for the next set of mats: while cheats destroy the mats, what about the possibility that they might also stand as their saviour? "It's just a matter of perspective," argues Rainey. The idea is beautifully simple, but counter-intuitive. Nonetheless, it offers potential solutions to profound problems such as the origins of reproduction, the soma / germ distinction -- even the origin of development itself.

In their experiments the researchers compared how two different life cycles affected group (mat) evolution. In the first, the mats were allowed to reproduce via a two-phase life cycle in which mats gave rise to mat offspring via cheater cells that functioned as a kind of germ line. In the second, cheats were purged and mats reproduced by fragmentation. "The viability of the resulting bacterial mats, that is, their biological fitness, improved under both scenarios, provided we allowed mats to compete with each other," explains Katrin Hammerschmidt of the New Zealand Institute for Advanced Study.

Surprisingly however, the researchers found that when cheats were part of the life cycle, the fitness of cellular collectives decoupled from that of the individual cells: that is, the most fit mats consisted of cells with relatively low individual fitness. "The selfish interests of individual cells in these collectives appear to have been conquered by natural selection working at the level of mats: individual cells ended up working for the common good. The resulting mats were thus more than a casual association of multiple cells. Instead, they developed into a new kind of biological entity -- a multicellular organism whose fitness can no longer be explained by the fitness of the individual cells that comprise the collective" says Rainey.

"Life cycles consisting of two phases are surprisingly similar to the life cycles of most multicellular organisms that we know today. It is even possible that germ-line cells, i.e. egg and sperm cells, may have emerged during the course of evolution from such selfish cheating cells," says Rainey.

From single cells to multicellular life: Researchers capture the emergence of multicellular life in real-time experiments

All multicellular creatures are descended from single-celled organisms. The leap from unicellularity to multicellularity is possible only if the originally independent cells collaborate. So-called cheating cells that exploit the cooperation of others are considered a major obstacle. Scientists at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in PlŲn, Germany, together with researchers from New Zealand and the USA, have observed in real time the evolution of simple self-reproducing groups of cells from previously individual cells. The nascent organisms are comprised of a single tissue dedicated to acquiring oxygen, but this tissue also generates cells that are the seeds of future generations: a reproductive division of labour. Intriguingly, the cells that serve as a germ line were derived from cheating cells whose destructive effects were tamed by integration into a life cycle that allowed groups to reproduce. The life cycle turned out to be a spectacular gift to evolution. Rather than working directly on cells, evolution was able to work on a developmental programme that eventually merged cells into a single organism. When this happened groups began to prosper with the once free-living cells coming to work for the good of the whole.

Single bacterial cells of Pseudomonas fluorescens usually live independently of each other. However, some mutations allow cells to produce adhesive glues that cause cells to remain stuck together after cell division. Under appropriate ecological conditions, the cellular assemblies can be favoured by natural selection, despite a cost to individual cells that produce the glues. When Pseudomonas fluorescens is grown in unshaken test tubes the cellular collectives prosper because they form mats at the surface of liquids where the cells gain access to oxygen that is otherwise -- in the liquid -- unavailable.

Given both costs associated with production of adhesive substances and benefits that accrue to the collective, natural selection is expected to favour types that no longer produce costly glues, but take advantage of the mat to support their own rapid growth. Such types are often referred to as cheats because they take advantage of the community effort while paying none of the costs. Cheats arise in the authors' experimental populations and bring about collapse of the mats. The mats fail when cheats prosper: cheats obtain an abundance of oxygen, but contribute no glue to keep the mat from disintegrating -- the mats eventually break and fall to the bottom where they are starved of oxygen.

Paul Rainey, who led the study at the New Zealand Institute for Advanced Study and the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology, explains: "Simple cooperating groups -- like the mats that interest us -- stand as one possible origin of multicellular life, but no sooner do the mats arise, than they fail: the same process that ensures their success -- natural selection -- , ensures their demise." But even more problematic is that groups, once extant, must have some means of reproducing themselves, else they are of little evolutionary consequence.

Pondering this problem led Rainey to an ingenious solution. What if cheats could act as seeds -- a germ line -- for the next set of mats: while cheats destroy the mats, what about the possibility that they might also stand as their saviour? "It's just a matter of perspective," argues Rainey. The idea is beautifully simple, but counter-intuitive. Nonetheless, it offers potential solutions to profound problems such as the origins of reproduction, the soma / germ distinction -- even the origin of development itself.

In their experiments the researchers compared how two different life cycles affected group (mat) evolution. In the first, the mats were allowed to reproduce via a two-phase life cycle in which mats gave rise to mat offspring via cheater cells that functioned as a kind of germ line. In the second, cheats were purged and mats reproduced by fragmentation. "The viability of the resulting bacterial mats, that is, their biological fitness, improved under both scenarios, provided we allowed mats to compete with each other," explains Katrin Hammerschmidt of the New Zealand Institute for Advanced Study.