BNW Brave New World

Samenzwering, verborgen agenda's en geheime geschiedenis. De zoektocht naar de wereld die achter de faÁade van alledag ligt.

...en de bezetting van Irak?

Met de kennis die ik heb kan ik het toch echt niet laten om alle punten te verbinden en voorlopig te concluderen dat er een grote kans is dat dit alles met opzet zo gelopen is. Irak straks opdelen, olie in handen van de Amerikanen en de Engelsen. Terrorisme vergroten om legitiem het Midden Oosten en Zuid Oost Azie te bezetten. Straks the endgame tussen de VS en GB vs China en Rusland, met Europa ergens ertussen in vanwege de afhankelijkheid van de olie en gas uit Rusland. Gelukkig hebben we tegen die tijd allemaal een paspoort en ID kaart met chip en biometrische gegevens, en gekoppelde databases, en camera's in de grote steden en speciale politieeenheden om onrusten hard de grond in te slaan.

Dit bovenstaande is een theorie, niet 100% mijn overtuiging, maar wel een theorie die ik mogelijk werkelijkheid zie worden in de komende 10-20 jaar.

Deze theorie basseer ik op basis van een aantal veronderstellingen.

Peak oil:

1. Olie is een finite resource, de meeste grote oliebronnen zijn al over hun piek productie heen, dit betekent dat de productiecapacitiet van deze velden met ongeveer 3% tot in sommige gevallen 6% daalt per jaar.

2. Er worden al sinds de jaren 80 geen grote olievelden meer gevonden, alle olievelden zijn nu z'n beetje wel ontdekt.

3. De rest van de grote olievelden die nog niet hun piek productie bereikt hebben zullen dit doen in de komende 10 jaar (optimistisch).

4. Onze levenswijze is zwaar afhankelijk van olie, denk aan de landbouw, transport, pharmacy en eigenlijk alle producten om je heen waar olie gebruikt is bij de vervaardiging of transport om bij jou te komen.

5. Economische groei is een vereiste om niet in een neerwaartse spiraal te komen. Economische groei vereist dat er meer geld in omloop komt elk jaar. We hebben met ons allen namelijk veel meer schulden dan dat er geld in de economie zit. Onze maatschappij wordt gedragen op deze schulden. Dit systeem werkt vooralsnog redelijk goed, het maakt je wel afhankelijk (slaaf) van het economische systeem, maar zolang je het goed doet in de maatschappij en de economie blijft groeien is er niks aan de hand.

6. Bedenk je nu eens in dat over een aantal jaar de olieprijs blijvend stijgt naar minimaal $100 per vat. Dit omdat onze economieen nog steeds groeien, dus mede onze vraag naar olie. Reken daarbij de opkomst van China en India en hun behoefte naar olie en de dalende productie van de grote olievelden en je hebt een tekort aan de aanbod zijde terwijl de vraag naar olie ongemoeid door blijft stijgen.

7. Alternatieven: natuurlijk zijn er dan alternatieven, er zullen nieuwe olievelden open gaan voor productie, kleine olievelden zullen economisch rendabel worden, olie uit teerzanden, en ontwikkeling van duurzame energie en waterstof zullen wat versneld gaan. Dit gebeurd echter pas als we de problemen gaan ondervinden, wanneer bedrijven minder winst maken of zelfs faillliet gaan. Een hoge olieprijs zal de economische groei sterk doen afnemen.

8. Dit was tot nu toe nog een vrij optimistische kijk. Neem hierbij nog ongeveer hetzelfde verhaaltje voor natural gas en kijk dan welke landen de grootste reserves hebben en waar wij onze olie en gas vandaan halen en je ziet dat meer dan 60% van de resterende olie en gas uit het Midden Oosten komt.

De verwachte piek in wereldproductie verschilt per onderzoeker, iedereen werkt met eigen data en modellen. De pessimisten zeggen tussen 2005 en 2010 en de "optimisten" nemen 2010 tot 2020 als uitgangsdatum.

Een aantal bronnen:

BBC - Is the world's oil running out fast?

Peakoil.nl - Wat is Peak Oil

Boeken

Richard Heinberg - The Party's Over

Kenneth Deffeyes - Hubbert's Peak

En nog vele anderen. Zoek op Peak oil

Geopolitiek

De VS verbruikt 25% van 's wereld olie, terwijl dit slechts 5% van de wereldpopulatie is. Azie (India en China) zijn samen goed voor 1 derde van de wereldpopulatie. Deze landen maken een extreme economische groei door en hebben op dit moment nauwelijks genoeg energie en andere grondstoffen om de groei bij te kunnen houden. Deze beide landen hebben bijna geen eigen energiebronnen en zijn compleet afhankelijk van olie en gas uit andere landen. Voornamelijk Iran. De VS was vroeger zelfvoorzienend in olie, evenals Engeland. Tegenwoordig importeren zij een groot deel van hun olie en gas. De toenemende vraag naar olie en gas drijft de prijs ver op. Van een gemiddelde prijs voor een vat olie van 10-20 Dollar in het begin van deze eeuw is de prijs gestegen tot 50-80 Dollar per vat. Natuurlijk zit hier ook heel wat speculatie in maar een prijs van onder $50 per vat zullen we waarschijnlijk niet meer zien.

Nou zijn onze wereldleiders niet dom. Dit hebben ze natuurlijk al lang zien aankomen. De CIA heeft in de jaren 70 al een study gedaan genaamd "Oil Fields as Military Objectives: A Feasibility Study" waarin overwogen werd om andere landen aan te vallen, te bezetten, puppet regeringen aan te stellen en sluipmoorden uit te voeren. Nog verder terug in de tijd zien we dat olie ook al een grote rol speelde bij de eerste wereldoorlog. Duitsland wilde een spoorlijn aanleggen naar Irak om zo toegang te krijgen tot de olie van het land. Dit wordt door velen gezien als een reden voor de eerste wereldoorlog. In feite begon de oorlog in Irak. (ottomaanse rijk) Een stuk later in 1953 werd de democratisch gekozen leider van Iran met behulp van de CIA en steun van de VS en GB afgezet nadat hij besloot de olie te nationaliseren. Het geld moest gebruikt worden voor eigen land en daarom moest de olie een nationaal goed worden. Big mistake.

The Grand Chessboard

In 1997 werd het boek The Grand Chessboard gepubliceerd, geschreven door Zbigniew Brzezinski voormalig National Security Advisor van President Jimmy Carter. In dit boek schrijft hij:

In 2000 Werd het rapport van The Poject for the New American Century gepubliceerd. Ik copy paste even als je het niet erg vind anders duurt het mij te lang om alles uit te leggen.

Het Project for the New American Century (PNAC, Project voor de Nieuwe Amerikaanse Eeuw) is een Amerikaanse, neoconservatieve denktank. PNAC werd in 1997 opgericht door het New Citizenship Project als een organisatie die zich het wereldwijde Amerikaanse leiderschap tot doel stelt. Leden van het PNAC zijn goed vertegenwoordigd in de Amerikaanse regeringen onder George W. Bush.

PNAC draagt de volgende kernpunten uit:

- Amerikaans leiderschap is goed voor zowel Amerika als de rest van de wereld;

- Zulk leiderschap vereist militaire kracht, diplomatieke energie en overtuiging aan morele principes;

- Te weinig leiders maken zich tegenwoordig sterk voor wereldwijd leiderschap.

- De inleiding van het PNAC-rapport "Rebuilding America's Defenses" (2000) noemt vier militaire kerndoelen:

- Het Amerikaanse thuisland beschermen;

- Tegelijkertijd meerdere belangrijke oorlogen overtuigend winnen;

- Politietaken uitvoeren

- Hervorming van de krijgsmacht

Wanneer je heel het document leest zie je dat ook zij de focus leggen op Eurasia.

De Bush administratie heeft in het begin van 2001 een onderzoek gedaan naar energy security (Cheney's Energy Task Force) en ziet de energievoorziening als een van de grootste bedreigingen voor het voortbestaan van de VS en de wereldeconomie. Het grootste deel van dit onderzoek is nog steeds classified.

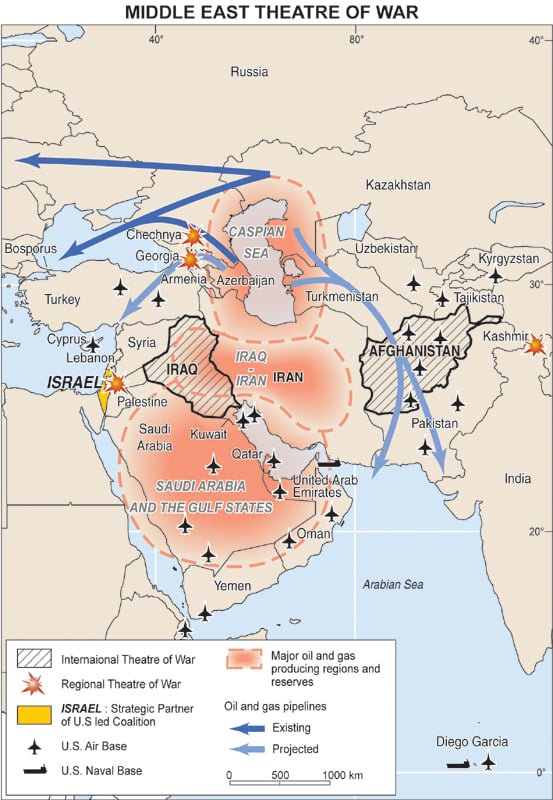

Op de map van Eurasia kan je goed zien dat de VS zowel China en Rusland buitensluit van het Midden Oosten en dat ze tegelijkertijd 's werelds grootste voorraad grondstoffen omsingeld hebben.

Dit is heel in het kort waar ik mijn mening op basseer en waarom ik het heel goed mogelijk acht dat bijvoorbeeld ook 9/11 een inside job zou kunnen zijn. Of er echt een endgame plaats zal vinden tussen China en de VS blijft natuurlijk gissen, de wereld zou ook veel meer kunnen gaan samenwerken en door middel van verdragen oplossingen bedenken, of er zou in het Midden Oosten een burgeroorlog kunnen uitbreken dat leidt tot een wereldoorlog, etc...

Wat is jullie visie hierop?

Bronnen:

Boeken:

Our Common Future

Limits to Growth: The 30-Year Update

The Party's Over: Oil, War and the Fate of Industrial Societies

Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict

The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives

PNAC - Rebuilding America's Defenses

The Pentagon's New Map: War and Peace in the Twenty-first Century van Thomas P.M. Barnett

Blueprint for Action: A Future Worth Creating van Thomas P.M. Barnett

A Century Of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order

Crossing the Rubicon: The Decline of the American Empire at the End of the Age of Oil

Filmpjes:

De Amerikaanse strategische planner Thomas Barnett. (torrents of p2p)

CSPAN - Thomas Barnett - Pentagon's New Map (2 uur 45 min)

CSPAN - Thomas Barnett - National Security Strategy (1 uur 15 min)

Analyse van het boek "The Grand Chessboard" door Michael Ruppert.

Michael Ruppert - The Grand Chessboard.avi (14 min)

BBC Documentaire "The War For Oil". AANRADER!!!

BBC Money Programme - The War For Oil Part 1 (10 min)

BBC Money Programme - The War For Oil Part 2 (10 min)

BBC Money Programme - The War For Oil Part 3 (9 min)

De documentaire The Oil Factor.

The Oil Factor op Video google

Beste stuk vanaf 8 minuten t/m 22. AANRADER!!!

Tweede stuk over de Afghaanse pijplijding vanaf 55 minuten t/m 1 uur 07 minuten.

Derde stuk, conclusie vanaf 1 uur 23 minuten t/m 1 uur 28 minuten.

Documentaire van PBS gericht op de geschiedenis van de schaduw regering van de VS.

PBS - Bill Moyers - The Secret Government: The Constitution in Crisis (22 min)

Als afsluiting een quote uit de film Three Days of the Condor

[ Bericht 0% gewijzigd door OpenYourMind op 09-11-2006 14:32:37 ]

Met de kennis die ik heb kan ik het toch echt niet laten om alle punten te verbinden en voorlopig te concluderen dat er een grote kans is dat dit alles met opzet zo gelopen is. Irak straks opdelen, olie in handen van de Amerikanen en de Engelsen. Terrorisme vergroten om legitiem het Midden Oosten en Zuid Oost Azie te bezetten. Straks the endgame tussen de VS en GB vs China en Rusland, met Europa ergens ertussen in vanwege de afhankelijkheid van de olie en gas uit Rusland. Gelukkig hebben we tegen die tijd allemaal een paspoort en ID kaart met chip en biometrische gegevens, en gekoppelde databases, en camera's in de grote steden en speciale politieeenheden om onrusten hard de grond in te slaan.

Dit bovenstaande is een theorie, niet 100% mijn overtuiging, maar wel een theorie die ik mogelijk werkelijkheid zie worden in de komende 10-20 jaar.

Deze theorie basseer ik op basis van een aantal veronderstellingen.

Peak oil:

1. Olie is een finite resource, de meeste grote oliebronnen zijn al over hun piek productie heen, dit betekent dat de productiecapacitiet van deze velden met ongeveer 3% tot in sommige gevallen 6% daalt per jaar.

2. Er worden al sinds de jaren 80 geen grote olievelden meer gevonden, alle olievelden zijn nu z'n beetje wel ontdekt.

3. De rest van de grote olievelden die nog niet hun piek productie bereikt hebben zullen dit doen in de komende 10 jaar (optimistisch).

4. Onze levenswijze is zwaar afhankelijk van olie, denk aan de landbouw, transport, pharmacy en eigenlijk alle producten om je heen waar olie gebruikt is bij de vervaardiging of transport om bij jou te komen.

5. Economische groei is een vereiste om niet in een neerwaartse spiraal te komen. Economische groei vereist dat er meer geld in omloop komt elk jaar. We hebben met ons allen namelijk veel meer schulden dan dat er geld in de economie zit. Onze maatschappij wordt gedragen op deze schulden. Dit systeem werkt vooralsnog redelijk goed, het maakt je wel afhankelijk (slaaf) van het economische systeem, maar zolang je het goed doet in de maatschappij en de economie blijft groeien is er niks aan de hand.

6. Bedenk je nu eens in dat over een aantal jaar de olieprijs blijvend stijgt naar minimaal $100 per vat. Dit omdat onze economieen nog steeds groeien, dus mede onze vraag naar olie. Reken daarbij de opkomst van China en India en hun behoefte naar olie en de dalende productie van de grote olievelden en je hebt een tekort aan de aanbod zijde terwijl de vraag naar olie ongemoeid door blijft stijgen.

7. Alternatieven: natuurlijk zijn er dan alternatieven, er zullen nieuwe olievelden open gaan voor productie, kleine olievelden zullen economisch rendabel worden, olie uit teerzanden, en ontwikkeling van duurzame energie en waterstof zullen wat versneld gaan. Dit gebeurd echter pas als we de problemen gaan ondervinden, wanneer bedrijven minder winst maken of zelfs faillliet gaan. Een hoge olieprijs zal de economische groei sterk doen afnemen.

8. Dit was tot nu toe nog een vrij optimistische kijk. Neem hierbij nog ongeveer hetzelfde verhaaltje voor natural gas en kijk dan welke landen de grootste reserves hebben en waar wij onze olie en gas vandaan halen en je ziet dat meer dan 60% van de resterende olie en gas uit het Midden Oosten komt.

De verwachte piek in wereldproductie verschilt per onderzoeker, iedereen werkt met eigen data en modellen. De pessimisten zeggen tussen 2005 en 2010 en de "optimisten" nemen 2010 tot 2020 als uitgangsdatum.

Een aantal bronnen:

BBC - Is the world's oil running out fast?

Peakoil.nl - Wat is Peak Oil

Boeken

Richard Heinberg - The Party's Over

Kenneth Deffeyes - Hubbert's Peak

En nog vele anderen. Zoek op Peak oil

Geopolitiek

De VS verbruikt 25% van 's wereld olie, terwijl dit slechts 5% van de wereldpopulatie is. Azie (India en China) zijn samen goed voor 1 derde van de wereldpopulatie. Deze landen maken een extreme economische groei door en hebben op dit moment nauwelijks genoeg energie en andere grondstoffen om de groei bij te kunnen houden. Deze beide landen hebben bijna geen eigen energiebronnen en zijn compleet afhankelijk van olie en gas uit andere landen. Voornamelijk Iran. De VS was vroeger zelfvoorzienend in olie, evenals Engeland. Tegenwoordig importeren zij een groot deel van hun olie en gas. De toenemende vraag naar olie en gas drijft de prijs ver op. Van een gemiddelde prijs voor een vat olie van 10-20 Dollar in het begin van deze eeuw is de prijs gestegen tot 50-80 Dollar per vat. Natuurlijk zit hier ook heel wat speculatie in maar een prijs van onder $50 per vat zullen we waarschijnlijk niet meer zien.

Nou zijn onze wereldleiders niet dom. Dit hebben ze natuurlijk al lang zien aankomen. De CIA heeft in de jaren 70 al een study gedaan genaamd "Oil Fields as Military Objectives: A Feasibility Study" waarin overwogen werd om andere landen aan te vallen, te bezetten, puppet regeringen aan te stellen en sluipmoorden uit te voeren. Nog verder terug in de tijd zien we dat olie ook al een grote rol speelde bij de eerste wereldoorlog. Duitsland wilde een spoorlijn aanleggen naar Irak om zo toegang te krijgen tot de olie van het land. Dit wordt door velen gezien als een reden voor de eerste wereldoorlog. In feite begon de oorlog in Irak. (ottomaanse rijk) Een stuk later in 1953 werd de democratisch gekozen leider van Iran met behulp van de CIA en steun van de VS en GB afgezet nadat hij besloot de olie te nationaliseren. Het geld moest gebruikt worden voor eigen land en daarom moest de olie een nationaal goed worden. Big mistake.

The Grand Chessboard

In 1997 werd het boek The Grand Chessboard gepubliceerd, geschreven door Zbigniew Brzezinski voormalig National Security Advisor van President Jimmy Carter. In dit boek schrijft hij:

Project for the New American Centuryquote:- "The last decade of the twentieth century has witnessed a tectonic shift in world affairs. For the first time ever, a non-Eurasian power has emerged not only as a key arbiter of Eurasian power relations but also as the world's paramount power. The defeat and collapse of the Soviet Union was the final step in the rapid ascendance of a Western Hemisphere power, the United States, as the sole and, indeed, the first truly global power." (p. xiii)

- "But in the meantime, it is imperative that no Eurasian challenger emerges, capable of dominating Eurasia and thus of also challenging America. The formulation of a comprehensive and integrated Eurasian geostrategy is therefore the purpose of this book." (p. xiv)

- "For America, the chief geopolitical prize is Eurasia" Now a non-Eurasian power is preeminent in Eurasia - and America's global primacy is directly dependent on how long and how effectively its preponderance on the Eurasian continent is sustained." (p.30)

- "America's withdrawal from the world or because of the sudden emergence of a successful rival - would produce massive international instability. It would prompt global anarchy." (p. 30)

- "In that context, how America manages' Eurasia is critical. Eurasia is the globe's largest continent and is geopolitically axial. A power that dominates Eurasia would control two of the world's three most advanced and economically productive regions. A mere glance at the map also suggests that control over Eurasia would almost automatically entail Africa's subordination, rendering the Western Hemisphere and Oceania geopolitically peripheral to the world's central continent. About 75 per cent of the world's people live in Eurasia, and most of the world's physical wealth is there as well, both in its enterprises and underneath its soil. Eurasia accounts for 60 per cent of the world's GNP and about three-fourths of the world's known energy resources." (p.31)

- Referring to an area he calls the "Eurasian Balkans" and a 1997 map in which he has circled the exact location of the current conflict - describing it as the central region of pending conflict for world dominance - Brzezinski writes: "Moreover, they [the Central Asian Republics] are of importance from the standpoint of security and historical ambitions to at least three of their most immediate and more powerful neighbors, namely Russia, Turkey and Iran, with China also signaling an increasing political interest in the region. But the Eurasian Balkans are infinitely more important as a potential economic prize: an enormous concentration of natural gas and oil reserves is located in the region, in addition to important minerals, including gold." (p.124) [Emphasis added]

- "The world's energy consumption is bound to vastly increase over the next two or three decades. Estimates by the U.S. Department of energy anticipate that world demand will rise by more than 50 percent between 1993 and 2015, with the most significant increase in consumption occurring in the Far East. The momentum of Asia's economic development is already generating massive pressures for the exploration and exploitation of new sources of energy and the Central Asian region and the Caspian Sea basin are known to contain reserves of natural gas and oil that dwarf those of Kuwait, the Gulf of Mexico, or the North Sea." (p.125)

- "It follows that America's primary interest is to help ensure that no single power comes to control this geopolitical space and that the global community has unhindered financial and economic access to it." (p148)

- "China's growing economic presence in the region and its political stake in the area's independence are also congruent with America's interests." (p.149)

- "America is now the only global superpower, and Eurasia is the globe's central arena. Hence, what happens to the distribution of power on the Eurasian continent will be of decisive importance to America's global primacy and to America's historical legacy." (p.194)

- "Without sustained and directed American involvement, before long the forces of global disorder could come to dominate the world scene. And the possibility of such a fragmentation is inherent in the geopolitical tensions not only of today's Eurasia but of the world more generally." (p.194)

- "With warning signs on the horizon across Europe and Asia, any successful American policy must focus on Eurasia as a whole and be guided by a Geostrategic design." (p.197)

- "That puts a premium on maneuver and manipulation in order to prevent the emergence of a hostile coalition that could eventually seek to challenge America's primacy." (p. 198)

- "The most immediate task is to make certain that no state or combination of states gains the capacity to expel the United States from Eurasia or even to diminish significantly its decisive arbitration role." (p. 198)

- "In the long run, global politics are bound to become increasingly uncongenial to the concentration of hegemonic power in the hands of a single state. Hence, America is not only the first, as well as the only, truly global superpower, but it is also likely to be the very last." (p.209)

- "Moreover, as America becomes an increasingly multi-cultural society, it may find it more difficult to fashion a consensus on foreign policy issues, except in the circumstance of a truly massive and widely perceived direct external threat." (p. 211) [Emphasis added]

Bron: A War in the Planning for Four Years

ps: ja ik het het boek ook zelf gelezen

In 2000 Werd het rapport van The Poject for the New American Century gepubliceerd. Ik copy paste even als je het niet erg vind anders duurt het mij te lang om alles uit te leggen.

Het Project for the New American Century (PNAC, Project voor de Nieuwe Amerikaanse Eeuw) is een Amerikaanse, neoconservatieve denktank. PNAC werd in 1997 opgericht door het New Citizenship Project als een organisatie die zich het wereldwijde Amerikaanse leiderschap tot doel stelt. Leden van het PNAC zijn goed vertegenwoordigd in de Amerikaanse regeringen onder George W. Bush.

PNAC draagt de volgende kernpunten uit:

- Amerikaans leiderschap is goed voor zowel Amerika als de rest van de wereld;

- Zulk leiderschap vereist militaire kracht, diplomatieke energie en overtuiging aan morele principes;

- Te weinig leiders maken zich tegenwoordig sterk voor wereldwijd leiderschap.

- De inleiding van het PNAC-rapport "Rebuilding America's Defenses" (2000) noemt vier militaire kerndoelen:

- Het Amerikaanse thuisland beschermen;

- Tegelijkertijd meerdere belangrijke oorlogen overtuigend winnen;

- Politietaken uitvoeren

- Hervorming van de krijgsmacht

Wanneer je heel het document leest zie je dat ook zij de focus leggen op Eurasia.

Cheney's Energy Task Forcequote:One of the possible strategic reasons for the USA to attack Iraq in 2003 was securing future oil supplies. Iraq has the world's second largest oil reserves, and much of it is also relatively cheap to extract and refine.

This strategy was designed by the organisation "Project for the New American Century”, among their members are Jeb Bush, Dick Cheney, Dan Quayle, Donald Rumsfeld and Paul Wolfowitz.

The attack upon Iraq is seen by some as part of a wider post 2001 redeployment of American forces, organised by Donald Rumsfeld to the Middle East and the oil rich Caspian basin.

However, the effectiveness of this military strategy has yet to be demonstrated, since the rate of rebuilding oil infrastructure has not greatly outpaced internal sabotage in Iraq.

Bron: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_policy_of_the_United_States

De Bush administratie heeft in het begin van 2001 een onderzoek gedaan naar energy security (Cheney's Energy Task Force) en ziet de energievoorziening als een van de grootste bedreigingen voor het voortbestaan van de VS en de wereldeconomie. Het grootste deel van dit onderzoek is nog steeds classified.

De VS en GB worden steeds afhankelijker van de olie in Eurasia. Europa is hier in mindere mata afhankelijk van maar weer meer afhankelijk van Rusland. India, maar voornamelijk China is desperate op zoek naar leveranciers van grondstoffen. Dit is wat een mogelijk conflict tussen deze landen mogelijk maakt. Vergeet niet dat China de grootste afnemer van Dollars is, zij kan letterlijk de Amerikaanse economie breken als ze wil. Op dit moment is economische oorlogsvoering een veel grotere dreiging en door middel van de informatie oorlog van tegenwoordig worden we afgeleid en weggeleid van wat er werkelijk speelt. Over enkele jaren zijn we waarschijnlijk afhankelijk van enkele bedrijven en een klein groepje elite die bepaald welke richting we opgaan.quote:The Energy Task Force is commonly known as the Cheney Energy Task Force after Vice President of the United States of America and former CEO of Halliburton, Dick Cheney.

In his second week in office George W. Bush created the task force, officially known as the National Energy Policy Development Group (NEPDG) with Dick Cheney as chairman. This group was supposed to develop an energy policy for the Bush administration. With both Bush and Cheney coming from the energy industry, which had contributed heavily to their campaign, and with the group proceeding in extreme secrecy, critics charged that the energy industry was exercising undue influence over national policy.

Congressmen Henry Waxman and John Dingell prompted the General Accounting Office (GAO), the investigative arm of Congress, to pursue Congress's oversight authority. Eventually the GAO filed a lawsuit known as Walker v. Cheney against the administration. This represented a power struggle between the legislative and executive branches. Judge John D. Bates, a recent Bush appointee, dismissed the case.

The activities of the Energy Task Force remain classified, even though Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests (since 19 April 2001) have sought to gain access to its materials. The organisations Judicial Watch and Sierra Club launched a law suit (U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia: Judicial Watch Inc. v. Department of Energy, et al., Civil Action No. 01-0981) under the FOIA to gain access to the task force's materials. On 5 March 2002 the US Government was ordered to make a full disclosure; this has not happened, pending appeal. In the Summer of 2003 a partial disclosure of these materials was made by the Commerce Department.

What was obtained were maps and charts, dated March 2001, of Iraq's, Saudi Arabia's and United Arab Emirates' oil fields, pipelines, refineries, tanker terminals and development projects.

Bron: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Energy_task_force

Op de map van Eurasia kan je goed zien dat de VS zowel China en Rusland buitensluit van het Midden Oosten en dat ze tegelijkertijd 's werelds grootste voorraad grondstoffen omsingeld hebben.

Dit is heel in het kort waar ik mijn mening op basseer en waarom ik het heel goed mogelijk acht dat bijvoorbeeld ook 9/11 een inside job zou kunnen zijn. Of er echt een endgame plaats zal vinden tussen China en de VS blijft natuurlijk gissen, de wereld zou ook veel meer kunnen gaan samenwerken en door middel van verdragen oplossingen bedenken, of er zou in het Midden Oosten een burgeroorlog kunnen uitbreken dat leidt tot een wereldoorlog, etc...

Wat is jullie visie hierop?

Bronnen:

Boeken:

Filmpjes:

De Amerikaanse strategische planner Thomas Barnett. (torrents of p2p)

CSPAN - Thomas Barnett - Pentagon's New Map (2 uur 45 min)

CSPAN - Thomas Barnett - National Security Strategy (1 uur 15 min)

Analyse van het boek "The Grand Chessboard" door Michael Ruppert.

Michael Ruppert - The Grand Chessboard.avi (14 min)

BBC Documentaire "The War For Oil". AANRADER!!!

BBC Money Programme - The War For Oil Part 1 (10 min)

BBC Money Programme - The War For Oil Part 2 (10 min)

BBC Money Programme - The War For Oil Part 3 (9 min)

De documentaire The Oil Factor.

The Oil Factor op Video google

Beste stuk vanaf 8 minuten t/m 22. AANRADER!!!

Tweede stuk over de Afghaanse pijplijding vanaf 55 minuten t/m 1 uur 07 minuten.

Derde stuk, conclusie vanaf 1 uur 23 minuten t/m 1 uur 28 minuten.

Documentaire van PBS gericht op de geschiedenis van de schaduw regering van de VS.

PBS - Bill Moyers - The Secret Government: The Constitution in Crisis (22 min)

Als afsluiting een quote uit de film Three Days of the Condor

quote:Higgins: It's simple economics. Today it's oil, right? In ten or fifteen years, food. Plutonium. Maybe even sooner. Now, what do you think the people are gonna want us to do then?

Joe Turner: Ask them?

Higgins: Not now - then! Ask 'em when they're running out. Ask 'em when there's no heat in their homes and they're cold. Ask 'em when their engines stop. Ask 'em when people who have never known hunger start going hungry. You wanna know something? They won't want us to ask 'em. They'll just want us to get it for 'em!

[ Bericht 0% gewijzigd door OpenYourMind op 09-11-2006 14:32:37 ]

"And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed - if all records told the same tale - then the lie passed into history and became truth. Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past."

idd , 95 views en nog geen serieuze reactiequote:Op donderdag 9 november 2006 16:16 schreef nonzz het volgende:

Dit is typisch zo'n OP waar je (of iig ik) niets mee kan.....

DeLuna vindt me dik ;(

Op zondag 22 juni 2014 12:30 schreef 3rdRock het volgende:

pas als jullie gaan trouwen. nu ben je gewoon die Oom Rubber die met onze mama leuke dingen doet :)

Op zondag 22 juni 2014 12:30 schreef 3rdRock het volgende:

pas als jullie gaan trouwen. nu ben je gewoon die Oom Rubber die met onze mama leuke dingen doet :)

Stormlooptopic

Ok, dit had ik ook wel enigzins verwacht. Mijn OP is niet echt geweldig coherent geschreven en neemt de lezer niet echt mee. Je moet er moeite voor doen als je wil weten waar het over gaat. Maar dat moet bij een topic die dieper in gaat op de buitenlandse politiek van de VS toch niet teveel gevraagd zijn?

Anyway, een samenvatting voor de mensen wiens tijd geld waard is.

Bovenstaande tekst gaat dus over de geopolitieke redenen achter de oorlog tegen het terrorisme. Ik stel dat het energiebeleid van de VS van grote invloed is op het buitenlandse beleid. De war on terror is slechts een excuus om de macht in het Midden Oosten uit te breiden vanwege de wereldwijd toenemende vraag naar energie en tegelijkertijd de dreiging van afnemende productie van olie. De afgelopen eeuw hebben we (de westerse wereld) 50% van de totale conventionele olie verbruikt en de grootste olievelden hebben hun maximale productiecapaciteit al gehad. De productie van deze velden neemt jaarlijks af met ongeveer 4 procent. De resterende olie (en gas) bevind zich grotendeels in het Midden Oosten, waar het westen en met name Amerika niet zo geliefd is. We worden dus steeds afhankelijker van een klein groepje landen voor een van de grootste basisbehoeften waarop onze samenleving gebouwd is. Olie is de motor geweest voor onze welvaart en economische groei.

Peak Oil

Peak Oil is de theorie die beschrijft dat elk olieveld een maximum productie capaciteit heeft en dat wanneer een olieveld de maximum capaciteit bereikt heeft de productie daarna gestaag afneemt. (3%+ per jaar) Wanneer een olieveld net ontdekt is staat deze onder grote druk waardoor de olie makkelijk uit de aarde te ontrekken is. Na verloop van tijd neemt de druk echter af en moet de druk kunstmatig hoog worden gehouden. Dit resulteert in een steeds minder zware kwaliteit van de olie. Wanneer de maximum capaciteit van een olieveld bereikt is (hoogste aantal vaten olie in een bepaald tijdsbestek) kan dit enige tijd volgehouden worden maar uiteindelijk zal de productie afnemen en wordt er steeds minder olie gewonnen. Dit geld wereldwijd voor alle oliebronnen.

Op wereldschaal is Peak Oil het groter worden van de vraag naar olie terwijl de oliebronnen over hun maximale productiecapaciteit heen gaan (production peak). Veel oliebronnen zijn al gepeakt, zo is het collectief aan oliebronnen in de VS al gepeakt begin jaren 70 en wordt er elk jaar minder olie geproduceerd. Men wordt dus afhankelijk van het buitenland voor de resterende vraag naar olie. Dit geldt voor bijna alle westerse landen. De verwachtingen zijn dat tussen nu en 2020 (ruim geschat) de wereldwijde olie peak plaatsvindt waarbij de vraag naar olie continu het aanbod zal overschrijden. Dit betekend dat de prijs van olie recordhoogten zal bereiken. Je ziet hier nu al het begin van. Sinds 2000 is de prijs van olie van 10-15 dollar per vat gestegen naar rond de $75,-. (de laatste weken wat gedaald naar rond de $60,-) Er wordt nu dus letterlijk gevochten voor de laatste oliereserves waarvan Irak en Iran nog grote onaangetaste olievoorraden in de grond hebben.

Voor een betere uitleg zie www.peakoil.nl.

Buitenland beleid VS

De Bush administratie heeft in het begin van 2001 een onderzoek gedaan naar energy security (Cheney Energy Task Force) en ziet de energievoorziening als een van de grootste bedreigingen voor het voortbestaan van de VS en de wereldeconomie. Het grootste deel van dit onderzoek is nog steeds classified.

Ander leesmateriaal waarin deze zorgen ook worden geuit zijn o.a. het boek van Zbigniew Brzezinski, “The Grand Chessboard” en het rapport van de denk tank genaamd “The Project of the New American Century (PNAC)”. Zij gaven al voor 2001 aan dat het voor de VS nodig is om de invloed in het Midden Oosten en Zuidoost AziŽ (60 procent van de wereld reserves aan grondstoffen) te vergroten voor het behouden van de Amerikaanse hegemonie. Hierbij worden grondstoffen en energie als belangrijkste argument (national security) gezien.

Na 9/11 besluit Bush (nou ja niet alleen Bush, maar de Neocons en de elite achter hem) om Afghanistan en Irak aan te vallen en vele militaire basissen te bouwen in het Midden Oosten, voornamelijk rondom het gebied met de grondstoffen. De plannen voor de invasie van Afghanistan en Irak waren er al ver voor 9/11. De complete legermacht was z'n beetje al in positie op 11 september 2001. Ten tijde van 9/11 ligt er dus al een grote troepenmacht klaar om het Midden Oosten in te trekken. Voor Rusland, China, India en nog wat andere landen was het al lang duidelijk dat er iets groots stond te gebeuren. Zij waarschuwen de VS al voor 9/11 met vrij gedetailleerde informatie over het plan van Al Qaeda om aanslagen met vliegtuigen in de VS te plegen. Wanneer de aanslagen op 9/11 plaatsvinden is het duidelijk, de VS gaat haar grip op het Midden Oosten vergroten.

Na de bezetting van Afghanistan en Irak is het aantal "vrijheidsstrijders" sterk toegenomen. In feite heeft het buitenlandse beleid ervoor gezorgd dat terrorisme groter is dan ooit tevoren. Komt dit de VS eigenlijk niet gewoon goed uit? En was het misschien niet de opzet van het hele plan? Op deze manier hebben ze een geldig motief om in het Midden Oosten te blijven. Nieuwe basissen zijn gebouwd, nieuwe puppet regimes zijn aangestelt en de VS heeft weer een grote stap gezet voor de energiezekerheid van de toekomst.

Wat denken jullie is dit werkelijk een reden (misschien de grootste reden) achter de war on terror?

Kijktip: De documentaire van de BBC "The War for Oil" en The Oil Factor die onderaan de OP staan.

Ok, dit had ik ook wel enigzins verwacht. Mijn OP is niet echt geweldig coherent geschreven en neemt de lezer niet echt mee. Je moet er moeite voor doen als je wil weten waar het over gaat. Maar dat moet bij een topic die dieper in gaat op de buitenlandse politiek van de VS toch niet teveel gevraagd zijn?

Anyway, een samenvatting voor de mensen wiens tijd geld waard is.

Bovenstaande tekst gaat dus over de geopolitieke redenen achter de oorlog tegen het terrorisme. Ik stel dat het energiebeleid van de VS van grote invloed is op het buitenlandse beleid. De war on terror is slechts een excuus om de macht in het Midden Oosten uit te breiden vanwege de wereldwijd toenemende vraag naar energie en tegelijkertijd de dreiging van afnemende productie van olie. De afgelopen eeuw hebben we (de westerse wereld) 50% van de totale conventionele olie verbruikt en de grootste olievelden hebben hun maximale productiecapaciteit al gehad. De productie van deze velden neemt jaarlijks af met ongeveer 4 procent. De resterende olie (en gas) bevind zich grotendeels in het Midden Oosten, waar het westen en met name Amerika niet zo geliefd is. We worden dus steeds afhankelijker van een klein groepje landen voor een van de grootste basisbehoeften waarop onze samenleving gebouwd is. Olie is de motor geweest voor onze welvaart en economische groei.

Peak Oil

Peak Oil is de theorie die beschrijft dat elk olieveld een maximum productie capaciteit heeft en dat wanneer een olieveld de maximum capaciteit bereikt heeft de productie daarna gestaag afneemt. (3%+ per jaar) Wanneer een olieveld net ontdekt is staat deze onder grote druk waardoor de olie makkelijk uit de aarde te ontrekken is. Na verloop van tijd neemt de druk echter af en moet de druk kunstmatig hoog worden gehouden. Dit resulteert in een steeds minder zware kwaliteit van de olie. Wanneer de maximum capaciteit van een olieveld bereikt is (hoogste aantal vaten olie in een bepaald tijdsbestek) kan dit enige tijd volgehouden worden maar uiteindelijk zal de productie afnemen en wordt er steeds minder olie gewonnen. Dit geld wereldwijd voor alle oliebronnen.

Op wereldschaal is Peak Oil het groter worden van de vraag naar olie terwijl de oliebronnen over hun maximale productiecapaciteit heen gaan (production peak). Veel oliebronnen zijn al gepeakt, zo is het collectief aan oliebronnen in de VS al gepeakt begin jaren 70 en wordt er elk jaar minder olie geproduceerd. Men wordt dus afhankelijk van het buitenland voor de resterende vraag naar olie. Dit geldt voor bijna alle westerse landen. De verwachtingen zijn dat tussen nu en 2020 (ruim geschat) de wereldwijde olie peak plaatsvindt waarbij de vraag naar olie continu het aanbod zal overschrijden. Dit betekend dat de prijs van olie recordhoogten zal bereiken. Je ziet hier nu al het begin van. Sinds 2000 is de prijs van olie van 10-15 dollar per vat gestegen naar rond de $75,-. (de laatste weken wat gedaald naar rond de $60,-) Er wordt nu dus letterlijk gevochten voor de laatste oliereserves waarvan Irak en Iran nog grote onaangetaste olievoorraden in de grond hebben.

Voor een betere uitleg zie www.peakoil.nl.

Buitenland beleid VS

De Bush administratie heeft in het begin van 2001 een onderzoek gedaan naar energy security (Cheney Energy Task Force) en ziet de energievoorziening als een van de grootste bedreigingen voor het voortbestaan van de VS en de wereldeconomie. Het grootste deel van dit onderzoek is nog steeds classified.

Ander leesmateriaal waarin deze zorgen ook worden geuit zijn o.a. het boek van Zbigniew Brzezinski, “The Grand Chessboard” en het rapport van de denk tank genaamd “The Project of the New American Century (PNAC)”. Zij gaven al voor 2001 aan dat het voor de VS nodig is om de invloed in het Midden Oosten en Zuidoost AziŽ (60 procent van de wereld reserves aan grondstoffen) te vergroten voor het behouden van de Amerikaanse hegemonie. Hierbij worden grondstoffen en energie als belangrijkste argument (national security) gezien.

Na 9/11 besluit Bush (nou ja niet alleen Bush, maar de Neocons en de elite achter hem) om Afghanistan en Irak aan te vallen en vele militaire basissen te bouwen in het Midden Oosten, voornamelijk rondom het gebied met de grondstoffen. De plannen voor de invasie van Afghanistan en Irak waren er al ver voor 9/11. De complete legermacht was z'n beetje al in positie op 11 september 2001. Ten tijde van 9/11 ligt er dus al een grote troepenmacht klaar om het Midden Oosten in te trekken. Voor Rusland, China, India en nog wat andere landen was het al lang duidelijk dat er iets groots stond te gebeuren. Zij waarschuwen de VS al voor 9/11 met vrij gedetailleerde informatie over het plan van Al Qaeda om aanslagen met vliegtuigen in de VS te plegen. Wanneer de aanslagen op 9/11 plaatsvinden is het duidelijk, de VS gaat haar grip op het Midden Oosten vergroten.

Na de bezetting van Afghanistan en Irak is het aantal "vrijheidsstrijders" sterk toegenomen. In feite heeft het buitenlandse beleid ervoor gezorgd dat terrorisme groter is dan ooit tevoren. Komt dit de VS eigenlijk niet gewoon goed uit? En was het misschien niet de opzet van het hele plan? Op deze manier hebben ze een geldig motief om in het Midden Oosten te blijven. Nieuwe basissen zijn gebouwd, nieuwe puppet regimes zijn aangestelt en de VS heeft weer een grote stap gezet voor de energiezekerheid van de toekomst.

Wat denken jullie is dit werkelijk een reden (misschien de grootste reden) achter de war on terror?

Kijktip: De documentaire van de BBC "The War for Oil" en The Oil Factor die onderaan de OP staan.

"And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed - if all records told the same tale - then the lie passed into history and became truth. Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past."

Yup!quote:Op donderdag 9 november 2006 19:46 schreef problematiQue het volgende:

goed artikel over dit onderwerp

Goed boek ook

Zijn website http://www.engdahl.oilgeopolitics.net/

"And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed - if all records told the same tale - then the lie passed into history and became truth. Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past."

Artikel uit de Economist waarom Peak Oil zeer waarschijnlijk niet voor binnenkort is:

Daarbij komt nog eens dat er een erg grote kans bestaat dat er nog grote olievelden diep in de zee onondekt zijn. Zie bv. http://www.worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=51837

Natuurlijk zijn deze allemaal veel duurder uit te baten, de tijd van 10$ per vat zal wel nooit meer terugkomen.

Olie zal imo zeker meegespeeld hebben bij het nemen van de beslissing om Irak en Afganistan binnen te vallen. Maar dan vooral om de stroom olie naar de westerse wereld te vrijwaren, en niet om er rechtstreeks veel geld mee te verdienen. De pijplijn door Afganistan bv. is er nog steeds niet en zal er waarschijnlijk ook in de nabije toekomst niet komen.

De war on terror is volgens mij gestart omdat er terroristen zijn die aanslagen willen plegen en de paniek daarvoor na 9/11. De aanpak ervan zal best wel wat bijgestuurd worden door belangen her en der, maar de hoofddoelstelling blijft imo.

Daarbij komt nog eens dat er een erg grote kans bestaat dat er nog grote olievelden diep in de zee onondekt zijn. Zie bv. http://www.worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=51837

Natuurlijk zijn deze allemaal veel duurder uit te baten, de tijd van 10$ per vat zal wel nooit meer terugkomen.

quote:Steady as she goes

Apr 20th 2006 | BAKERSFIELD, CALIFORNIA, AND CALGARY, ALBERTA

From The Economist print edition

Why the world is not about to run out of oil

IN 1894 Le Petit Journal of Paris organised the world's first endurance race for “vehicles without horses”. The race was held on the 78-mile (125km) route from Paris to Rouen, and the purse was a juicy 5,000 francs. The rivals used all manner of fuels, ranging from steam to electricity to compressed air. The winner was a car powered by a strange new fuel that had previously been used chiefly in illumination, as a substitute for whale blubber: petrol derived from oil.

Despite the victory, petrol's future seemed uncertain back then. Internal-combustion vehicles were seen as noisy, smelly and dangerous. By 1900 the market was still split equally among steam, electricity and petrol—and even Henry Ford's Model T ran on both grain-alcohol and petrol. In the decades after that great race petrol came to dominate the world's transportation system. Oil left its rivals in the dust not only because internal-combustion engines proved more robust and powerful than their rivals, but also because oil reserves proved to be abundant.

Now comes what appears to be the most powerful threat to oil's supremacy in a century: growing fears that the black gold is running dry. For years a small group of geologists has been claiming that the world has started to grow short of oil, that alternatives cannot possibly replace it and that an imminent peak in production will lead to economic disaster. In recent months this view has gained wider acceptance on Wall Street and in the media. Recent books on oil have bewailed the threat. Every few weeks, it seems, “Out of Gas”, “The Empty Tank” and “The Coming Economic Collapse: How You Can Thrive When Oil Costs $200 a Barrel”, are joined by yet more gloomy titles. Oil companies, which once dismissed the depletion argument out of hand, are now part of the debate. Chevron's splashy advertisements strike an ominous tone: “It took us 125 years to use the first trillion barrels of oil. We'll use the next trillion in 30.” Jeroen van der Veer, chief executive of Royal Dutch Shell, believes “the debate has changed in the last two years from 'Can we afford oil?' to 'Is the oil there?'”

But is the world really starting to run out of oil? And would hitting a global peak of production necessarily spell economic ruin? Both questions are arguable. Despite today's obsession with the idea of “peak oil”, what really matters to the world economy is not when conventional oil production peaks, but whether we have enough affordable and convenient fuel from any source to power our current fleet of cars, buses and aeroplanes. With that in mind, the global oil industry is on the verge of a dramatic transformation from a risky exploration business into a technology-intensive manufacturing business. And the product that big oil companies will soon be manufacturing, argues Shell's Mr Van der Veer, is “greener fossil fuels”.

The race is on to manufacture such fuels for blending into petrol and diesel today, thus extending the useful life of the world's remaining oil reserves. This shift in emphasis from discovery to manufacturing opens the door to firms outside the oil industry (such as America's General Electric, Britain's Virgin Fuels and South Africa's Sasol) that are keen on alternative energy. It may even result in a breakthrough that replaces oil altogether.

To see how that might happen, consider the first question: is the world really running out of oil? Colin Campbell, an Irish geologist, has been saying since the 1990s that the peak of global oil production is imminent. Kenneth Deffeyes, a respected geologist at Princeton, thought that the peak would arrive late last year.

It did not. In fact, oil production capacity might actually grow sharply over the next few years (see chart 1). Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), an energy consultancy, has scrutinised all of the oil projects now under way around the world. Though noting rising costs, the firm concludes that the world's oil-production capacity could increase by as much as 15m barrels per day (bpd) between 2005 and 2010—equivalent to almost 18% of today's output and the biggest surge in history. Since most of these projects are already budgeted and in development, there is no geological reason why this wave of supply will not become available (though politics or civil strife can always disrupt output).

Peak-oil advocates remain unconvinced. A sign of depletion, they argue, is that big Western oil firms are finding it increasingly difficult to replace the oil they produce, let alone build their reserves. Art Smith of Herold, a consultancy, points to rising “finding and development” costs at the big firms, and argues that the world is consuming two to three barrels of oil for every barrel of new oil found. Michael Rodgers of PFC Energy, another consultancy, says that the peak of new discoveries was long ago. “We're living off a lottery we won 30 years ago,” he argues.

It is true that the big firms are struggling to replace reserves. But that does not mean the world is running out of oil, just that they do not have access to the vast deposits of cheap and easy oil that are left in Russia and members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). And as the great fields of the North Sea and Alaska mature, non-OPEC oil production will probably peak by 2010 or 2015. That is soon—but it says nothing of what really matters, which is the global picture.

When the United States Geological Survey (USGS) studied the matter closely, it concluded that the world had around 3 trillion barrels of recoverable conventional oil in the ground. Of that, only one-third has been produced. That, argued the USGS, puts the global peak beyond 2025. And if “unconventional” hydrocarbons such as tar sands and shale oil (which can be converted with greater effort to petrol) are included, the resource base grows dramatically—and the peak recedes much further into the future.

After Ghawar

It is also true that oilmen will probably discover no more “super-giant” fields like Saudi Arabia's Ghawar (which alone produces 5m bpd). But there are even bigger resources available right under their noses. Technological breakthroughs such as multi-lateral drilling helped defy predictions of decline in Britain's North Sea that have been made since the 1980s: the region is only now peaking.

Globally, the oil industry recovers only about one-third of the oil that is known to exist in any given reservoir. New technologies like 4-D seismic analysis and electromagnetic “direct detection” of hydrocarbons are lifting that “recovery rate”, and even a rise of a few percentage points would provide more oil to the market than another discovery on the scale of those in the Caspian or North Sea.

Further, just because there are no more Ghawars does not mean an end to discovery altogether. Using ever fancier technologies, the oil business is drilling in deeper waters, more difficult terrain and even in the Arctic (which, as global warming melts the polar ice cap, will perversely become the next great prize in oil). Large parts of Siberia, Iraq and Saudi Arabia have not even been explored with modern kit.

The petro-pessimists' most forceful argument is that the Persian Gulf, officially home to most of the world's oil reserves, is overrated. Matthew Simmons, an American energy investment banker, argues in his book, “Twilight in the Desert”, that Saudi Arabia's oil fields are in trouble. In recent weeks a scandal has engulfed Kuwait, too. Petroleum Intelligence Weekly (PIW), a respected industry newsletter, got hold of government documents suggesting that Kuwait might have only half of the nearly 100 billion barrels in oil reserves that it claims (Saudi Arabia claims 260 billion barrels).

Tom Wallin, publisher of PIW, warns that “the lesson from Kuwait is that the reserves figures of national governments must be viewed with caution.” But that still need not mean that a global peak is imminent. So vast are the remaining reserves, and so well distributed are today's producing areas, that a radical revision downwards—even in an OPEC country—does not mean a global peak is here.

For one thing, Kuwait's official numbers always looked dodgy. IHS Energy, an industry research outfit that constructs its reserve estimates from the bottom up rather than relying on official proclamations, had long been using a figure of 50 billion barrels for Kuwait. Ron Mobed, boss of IHS, sees no crisis today: “Even using our smaller number, Kuwait still has 50 years of production left at current rates.” As for Saudi Arabia, most independent contractors and oil majors that have first-hand knowledge of its fields are convinced that the Saudis have all the oil they claim—and that more remains to be found.

Pessimists worry that Saudi Arabia's giant fields could decline rapidly before any new supply is brought online. In Jeremy Leggett's thoughtful, but gloomy, book, “The Empty Tank”, Mr Simmons laments that “the only alternative right now is to shrink our economies.” That poses a second big question: whenever the production peak comes, will it inevitably prompt a global economic crisis?

The baleful thesis arises from concerns both that a cliff lies beyond any peak in production and that alternatives to oil will not be available. If the world oil supply peaked one day and then fell away sharply, prices would indeed rocket, shortages and panic buying would wreak havoc and a global recession would ensue. But there are good reasons to think that a global peak, whenever it comes, need not lead to a collapse in output.

For one thing, the nightmare scenario of Ghawar suddenly peaking is not as grim as it first seems. When it peaks, the whole “super-giant” will not drop from 5m bpd to zero, because it is actually a network of inter-linked fields, some old and some newer. Experts say a decline would probably be gentler and prolonged. That would allow, indeed encourage, the Saudis to develop new fields to replace lost output. Saudi Arabia's oil minister, Ali Naimi, points to an unexplored area on the Iraqi-Saudi border the size of California, and argues that such untapped resources could add 200 billion barrels to his country's tally. This contains worries of its own—Saudi Arabia's market share will grow dramatically as non-OPEC oil peaks, and with it the potential for mischief. But it helps to debunk claims of a sudden change.

The notion of a sharp global peak in production does not withstand scrutiny, either. CERA's Peter Jackson points out that the price signals that would surely foreshadow any “peak” would encourage efficiency, promote new oil discoveries and speed investments in alternatives to oil. That, he reckons, means the metaphor of a peak is misleading: “The right picture is of an undulating plateau.”

What of the notion that oil scarcity will lead to economic disaster? Jerry Taylor and Peter Van Doren of the Cato Institute, an American think-tank, insist the key is to avoid the price controls and monetary-policy blunders of the sort that turned the 1970s oil shocks into economic disasters. Kenneth Rogoff, a Harvard professor and the former chief economist of the IMF, thinks concerns about peak oil are greatly overblown: “The oil market is highly developed, with worldwide trading and long-dated futures going out five to seven years. As oil production slows, prices will rise up and down the futures curve, stimulating new technology and conservation. We might be running low on $20 oil, but for $60 we have adequate oil supplies for decades to come.”

The other worry of pessimists is that alternatives to oil simply cannot be brought online fast enough to compensate for oil's imminent decline. If the peak were a cliff or if it arrived soon, this would certainly be true, since alternative fuels have only a tiny global market share today (though they are quite big in markets, such as ethanol-mad Brazil, that have favourable policies). But if the peak were to come after 2020 or 2030, as the International Energy Agency and other mainstream forecasters predict, then the rising tide of alternative fuels will help transform it into a plateau and ease the transition to life after oil.

The best reason to think so comes from the radical transformation now taking place among big oil firms. The global oil industry, argues Chevron, is changing from “an exploration business to a manufacturing business”. To see what that means, consider the surprising outcome of another great motorcar race. In March, at the Sebring test track in Florida, a sleek Audi prototype R-10 became the first diesel-powered car to win an endurance race, pipping a field of petrol-powered rivals to the post. What makes this tale extraordinary is that the diesel used by the Audi was not made in the normal way, exclusively from petroleum. Instead, Shell blended conventional diesel with a super-clean and super-powerful new form of diesel made from natural gas (with the clunky name of gas-to-liquids, or GTL).

Several big GTL projects are under way in Qatar, where the North gas field is perhaps twice the size of even Ghawar when measured in terms of the energy it contains. Nigeria and others are also pursuing GTL. Since the world has far more natural gas left than oil—much of it outside the Middle East—making fuel in this way would greatly increase the world's remaining supplies of oil.

So, too, would blending petrol or diesel with ethanol and biodiesel made from agricultural crops, or with fuel made from Canada's “tar sands” or America's shale oil. Using technology invented in Nazi Germany and perfected by South Africa's Sasol when those countries were under oil embargoes, companies are now also investing furiously to convert not only natural gas but also coal into a liquid fuel. Daniel Yergin of CERA says “the very definition of oil is changing, since non-conventional oil becomes conventional over time.”

Alternative fuels will not become common overnight, as one veteran oilman acknowledges: “Given the capital-intensity of manufacturing alternatives, it's now a race between hydrocarbon depletion and making fuel.” But the recent rise in oil prices has given investors confidence. As Peter Robertson, vice-chairman of Chevron, puts it, “Price is our friend here, because it has encouraged investment in new hydrocarbons and also the alternatives.” Unless the world sees another OPEC-engineered price collapse as it did in 1985 and 1998, GTL, tar sands, ethanol and other alternatives will become more economic by the day (see chart 2).

This is not to suggest that the big firms are retreating from their core business. They are pushing ahead with these investments mainly because they cannot get access to new oil in the Middle East: “We need all the molecules we can get our hands on,” says one oilman. It cannot have escaped the attention of oilmen that blending alternative fuels into petrol and diesel will conveniently reinforce oil's grip on transport. But their work contains the risk that one of the upstart fuels could yet provide a radical breakthrough that sidelines oil altogether.

If you doubt the power of technology or the potential of unconventional fuels, visit the Kern River oil field near Bakersfield, California. This super-giant field is part of a cluster that has been pumping out oil for more than 100 years. It has already produced 2 billion barrels of oil, but has perhaps as much again left. The trouble is that it contains extremely heavy oil, which is very difficult and costly to extract. After other companies despaired of the field, Chevron brought Kern back from the brink. Applying a sophisticated steam-injection process, the firm has increased its output beyond the anticipated peak. Using a great deal of automation (each engineer looks after 1,000 small wells drilled into the reservoir), the firm has transformed a process of “flying blind” into one where wells “practically monitor themselves and call when they need help”.

The good news is that this is not unique. China also has deposits of heavy oil that would benefit from such an advanced approach. America, Canada and Venezuela have deposits of heavy hydrocarbons that surpass even the Saudi oil reserves in size. The Saudis have invited Chevron to apply its steam-injection techniques to recover heavy oil in the neutral zone that the country shares with Kuwait. Mr Naimi, the oil minister, recently estimated that this new technology would lift the share of the reserve that could be recovered as useful oil from a pitiful 6% to above 40%.

All this explains why, in the words of Exxon Mobil, the oil production peak is unlikely “for decades to come”. Governments may decide to shift away from petroleum because of its nasty geopolitics or its contribution to global warming. But it is wrong to imagine the world's addiction to oil will end soon, as a result of genuine scarcity. As Western oil companies seek to cope with being locked out of the Middle East, the new era of manufactured fuel will further delay the onset of peak production. The irony would be if manufactured fuel also did something far more dramatic—if it served as a bridge to whatever comes beyond the nexus of petrol and the internal combustion engine that for a century has held the world in its grip.

Olie zal imo zeker meegespeeld hebben bij het nemen van de beslissing om Irak en Afganistan binnen te vallen. Maar dan vooral om de stroom olie naar de westerse wereld te vrijwaren, en niet om er rechtstreeks veel geld mee te verdienen. De pijplijn door Afganistan bv. is er nog steeds niet en zal er waarschijnlijk ook in de nabije toekomst niet komen.

De war on terror is volgens mij gestart omdat er terroristen zijn die aanslagen willen plegen en de paniek daarvoor na 9/11. De aanpak ervan zal best wel wat bijgestuurd worden door belangen her en der, maar de hoofddoelstelling blijft imo.

Die tegenlicht docu's hierover zijn echt de bom

http://www.vpro.nl/programma/tegenlicht/afleveringen/

http://www.vpro.nl/programma/tegenlicht/afleveringen/

Zeer goede documentaires, op de ongenuanceerde beschuldigingen tegen Venezuela na. Verder vind ik die Thomas Friedman maar een irritante en arrogante man. Hij heeft duidelijk zijn eigen agenda. Heb wel zijn boek besteld, omdat zijn denkbeelden erg grote invloed hebben.quote:Op donderdag 9 november 2006 20:30 schreef meurdoos het volgende:

Die tegenlicht docu's hierover zijn echt de bom

http://www.vpro.nl/programma/tegenlicht/afleveringen/

Dit artikel over hoe Rusland voormalige sovjet staten onder druk zet is ook zeer interessant evenals de hele affaire rond de oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky en zijn bedrijf Yukos.

Putin zorgde voor de arrestatie van de oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky waarop andere betrokken oligarchen vluchten naar London en Israel. Het bedrijf Yukos werd later per opbod verkocht voor iets meer dan 9 miljard aan Baikalfinansgroup. Een bedrijf waar niemand ooit van gehoord had en later een snel opgezette shell company blijkt van de staat. Yukos is naderhand namelijk netjes overgedragen aan het staatsbedrijf Rosneft.quote:Europa op de knieen voor Poetin - deel 1

De ex-Sovjet Staten, controle over de exportpijpleidingen naar Europa.

Na Wit Rusland, ArmeniŽ, Litouwen, Estland, Letland, MoldaviŽ en OekraÔne is nu GeorgiŽ aan de beurt. De boodschap is helder, zodra er een leveringscontract voor aardgas afloopt dwingt Rusland haar “klanten” tot een keuze. Of je betaalt steeds meer, tot aan de Europese marktprijs van 250 dollar per duizend kubieke meter, of je geeft een stuk van je infrastructuur, vrijwel gratis, aan Rusland. Het doel is tweeledig, ten eerste wil Rusland zoveel mogelijk controle krijgen over haar exportpijpleidingen naar Europa die ze door de val van de Sovjetunie verloren is. Ten tweede heeft Rusland veel meer inkomsten nodig, om moeilijk winbare gasreserves af te tappen omdat de productie in haar grote oude gasvelden hard terugloopt. Poetin weet dat de ex-Sovjet staten de marktprijs niet kunnen betalen en dus wel door de knieŽn moeten gaan. Hieronder een overzicht van de ontwikkelingen in de afgelopen twee jaar.

Bron: Europa op de knieen voor Poetin - deel 1

quote:Yukos-concurrent achter onbekende bieder

zondag 19 december 2004

De winnaar van de veiling van de productiedivisie van de Russische oliegigant Yukos is naar alle waarschijnlijkheid verbonden aan een concurrent, olieproducent Surgutneftegaz. Heel verrassend kocht de onbekende Baikalfinansgroup zondag 19 december op een veiling Yuganskneftegaz, de belangrijkste dochteronderneming van Yukos. De Baikalfinansgroup heeft 7 miljard euro voor het bedrijf betaald.

Bron: http://www.elsevier.nl/ni(...)tnr/17418/index.html

Op wikipedia staat een stuk over deze mysterieuze investeringsgroep en de overname.quote:Yukos toch in handen van Russische staat

donderdag 23 december 2004

De Russische president Vladimir Poetin is de grote winnaar in de strijd om oliegigant Yukos. Het staatsbedrijf Rosneft is eigenaar geworden van Yuganskneftegaz, de productiedivisie van Yukos.

Rosneft nam donderdag 23 december het onderdeel over van het onbekende investeringsbedrijf Baikalfinansgroup, dat Yuganskneftegaz zondag op een veiling voor 9,35 miljard dollar had gekocht. Hoeveel Rosneft voor het belangrijkste Yukos-onderdeel heeft neergeteld, is niet bekendgemaakt.

Bron: http://www.elsevier.nl/ni(...)tnr/18191/index.html

Zie ook de documentaire van de BBC The Russian Godfathersquote:Baikalfinansgrup

Baikalfinansgrup (Russian: Байкалфинансгруп) is a Russian limited liability company owned by Rosneft Oil Company. It is best known as the company that won the December 19, 2004 auction for a 76.79% share in Yuganskneftegaz, formerly the core production subsidiary of Yukos Oil Company. Baikalfinansgrup won the auction with a bid of 261 billion rubles (US $9.3 bn), which was somewhere between 37-49% of Yuganskneftegaz’ market value at the time, according to an appraisal made by Dresdner Kleinwort Wasserstein and JPMorgan Chase & Co. [1].

Profile

Baikalfinansgrup was created on December 6, 2004, just two weeks before the Yuganskneftegaz auction, with a share capital of 10,000 rubles ($358 US). Its original registered address was in the north-western Russian city of Tver in a building that houses a vodka bar, a mobile phone shop, a tour operator agency and the offices of several small local companies, but no office of Baikalfinansgrup. Baykalfinansgrup later moved its legal address to the head office of Rosneft Oil Company, which is situated on Sofiyskaya Embankment directly opposite the Kremlin.

Despite its obscurity, Baikalfinansgrup was able to secure a credit of US $1.7 bn from the state-owned Sberbank savings bank as a down-payment for participating in the auction.

On December 21, 2004, Russian president Vladimir Putin admitted that he knew the owners of Baikalfinansgrup. Putin did not disclose their names but noted that they were individuals with ‘many years of experience in the energy business’.

Bron: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Baikalfinansgroup

Wat mij nog meer verbaasde was dit bericht waaruit dan weer blijkt dat dit nog veel dieper gaat dan alleen Yukos. Putin was nota bene door de oligarchen aan de macht geholpen. Hoe en wat precies weet ik niet maar als een Rothschild hierbij betrokken is dan is er meer aan de hand.

quote:Arrested oil tycoon passed shares to banker

LONDON (Agence France-Presse) — Control of Mikhail Khodorkovsky's shares in the Russian oil giant Yukos have passed to renowned banker Jacob Rothschild, under a deal they concluded prior to Mr. Khodorkovsky's arrest, the Sunday Times reported.

Voting rights to the shares passed to Mr. Rothschild, 67, under a "previously unknown arrangement" designed to take effect in the event that Mr. Khodorkovsky could no longer "act as a beneficiary" of the shares, it said. Mr. Khodorkovsky, 40, whom Russian authorities arrested at gunpoint and jailed pending further investigation last week, was said by the Sunday Times to have made the arrangement with Mr. Rothschild when he realized he was facing arrest.

Mr. Rothschild now controls the voting rights on a stake in Yukos worth almost $13.5 billion, the newspaper said in a dispatch from Moscow. Mr. Khodorkovsky owns 4 percent of Yukos directly and 22 percent through a trust of which he is the sole beneficiary, according to Russian analysts. From the figures reported in the Sunday Times, it appeared Mr. Rothschild had received control of all Mr. Khodorkovsky's shares. The two have known each other for years "through their mutual love of the arts" and their positions as directors of the Open Russia Foundation, Yukos' philanthropic branch, it said.

Russian authorities Thursday froze billions of dollars of shares held by Mr. Khodorkovsky and his top lieutenants in Yukos — throwing control of the country's largest oil company into limbo and causing frenzied selling on financial markets. Russian prosecutors said owners of the shares are still entitled to dividends and retain voting rights, but can no longer sell their stakes. They said the freeze was necessary as collateral for the $1 billion that Mr. Khodorkovsky and his associates are accused of misappropriating during the 1990s. Mr. Rothschild is the British head of Europe's wealthy and influential Rothschild family, and runs his own investment empire.

Bron: http://washingtontimes.com/world/20031102-111400-3720r.htm

"And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed - if all records told the same tale - then the lie passed into history and became truth. Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past."

Nu weten meteen waarom de eigenaar van Yukos achter tralies moest.

[ Bericht 88% gewijzigd door Finder_elf_towns op 09-11-2006 21:38:26 ]

[ Bericht 88% gewijzigd door Finder_elf_towns op 09-11-2006 21:38:26 ]

Ik vind het trouwens wel jammer dat ze de olielanden alleen vanuit onze westerse denkwijzes bekijken. Voornamelijk bij Venezuela en Zuid Amerika zit er een veel diepere geschiedenis achter. Zelfde bij Rusland. Als ze daar echt de geopolitieke belangen bloot zouden leggen en het in een historische context plaatsen krijg je een veel kritischere kijk op de westerse geschiedenis en die zogenaamde vrije markt van Friedman.quote:Op donderdag 9 november 2006 20:30 schreef meurdoos het volgende:

Die tegenlicht docu's hierover zijn echt de bom

http://www.vpro.nl/programma/tegenlicht/afleveringen/

Als ze dan ook nog eens gaan kijken waarom we in het westen nog niet meer hebben gedaan aan duurzame energie en wat voor een corruptie er achter onze westerse ("vrije markt" en kapitalistische) instituten en bedrijven zit dan heb je pas een klein beetje een beeld over wat er allemaal achter deze mogelijk energy wars zit.

"And if all others accepted the lie which the Party imposed - if all records told the same tale - then the lie passed into history and became truth. Who controls the past controls the future, who controls the present controls the past."

VS heeft toch Irak aangevallen omdat ze hun olie in euro's wilden verhandelen? En dat zou de alleenheerschappij van de Amerikaanse dollar in gevaar brengen, en dat is met name gevaarlijk omdat Amerika een groot handelstekort heeft.

President Camacho

TV series: Boardwalk Empire | Burn Notice | Dexter | Game of Thrones | Impractical Jokers | Luther | Sherlock | Sons of Anarchy

TV series: Boardwalk Empire | Burn Notice | Dexter | Game of Thrones | Impractical Jokers | Luther | Sherlock | Sons of Anarchy

De "wetenschappers" Jerome R. Corsi and Craig R. Smith worden in de wetenschappelijke wereld niet echt op handen gedragen, er is nog totaal geen bewijs voor hun abiotische olie theorie behalve wishfull thinking. Dat er nog grote olievelden diep in de zee zijn is goed mogelijk. De vraag is echter of we de techniek hebben om deze in productie te brengen en of dit een significante bijdrage kan leveren aan het aantal barrels per dag. Verder kan abiotische olie best waar zijn, maar tot nu toe is nog nergens gebleken dat de olie in andere velden bijgevult wordt uit de aarde en al helemaal niet of dit tempo voldoende is. Als de olievelden echt bijgevult worden dan hadden we dat nu al wel gemerkt. De diepere olievelden zouden hierop een uitzondering kunnen zijn, maar dan nog is het zeer speculatief.quote:Op donderdag 9 november 2006 20:27 schreef gorgg het volgende:

Artikel uit de Economist waarom Peak Oil zeer waarschijnlijk niet voor binnenkort is:

Daarbij komt nog eens dat er een erg grote kans bestaat dat er nog grote olievelden diep in de zee onondekt zijn. Zie bv. http://www.worldnetdaily.com/news/article.asp?ARTICLE_ID=51837

Natuurlijk zijn deze allemaal veel duurder uit te baten, de tijd van 10$ per vat zal wel nooit meer terugkomen.

Mee eens. Het vertrouwen is dus op nieuwe technologie. De vraag blijft echter of dit aan de stijgende vraag naar energie kan voldoen. Dat is dus een kwestie van koffiedik kijken, waar bijna iedere wetenschapper een andere kijk op heeft.quote:Artikel Economist

But is the world really starting to run out of oil? And would hitting a global peak of production necessarily spell economic ruin? Both questions are arguable. Despite today's obsession with the idea of “peak oil”, what really matters to the world economy is not when conventional oil production peaks, but whether we have enough affordable and convenient fuel from any source to power our current fleet of cars, buses and aeroplanes. With that in mind, the global oil industry is on the verge of a dramatic transformation from a risky exploration business into a technology-intensive manufacturing business. And the product that big oil companies will soon be manufacturing, argues Shell's Mr Van der Veer, is “greener fossil fuels”.

Waarbij ze impliciet dus eigenlijk zeggen dat we nu nog maar net de vraag kunnen bijhouden en dat de verwachtingen zijn dat er misschien de komende jaren nog genoeg oude velden en wat alternatieven ontwikkeld worden die het aanbod iets kunnen verhogen. 15m barrels per dag is natuurlijk wel een uitermate optimistische schatting.quote:To see how that might happen, consider the first question: is the world really running out of oil? Colin Campbell, an Irish geologist, has been saying since the 1990s that the peak of global oil production is imminent. Kenneth Deffeyes, a respected geologist at Princeton, thought that the peak would arrive late last year.

It did not. In fact, oil production capacity might actually grow sharply over the next few years (see chart 1). Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA), an energy consultancy, has scrutinised all of the oil projects now under way around the world. Though noting rising costs, the firm concludes that the world's oil-production capacity could increase by as much as 15m barrels per day (bpd) between 2005 and 2010—equivalent to almost 18% of today's output and the biggest surge in history. Since most of these projects are already budgeted and in development, there is no geological reason why this wave of supply will not become available (though politics or civil strife can always disrupt output).

Bewijs eerst maar eens dat die er zijn. De reserves van de OPEC landen zijn eind jaren 80 bijna verdubbeld vanwege een regeling waarbij men meer olie mag produceren naarmate de reserves hoger zijn. Ook blijven de reserves al jaren hetzelfde ook al wordt er wel gewoon geproduceerd. Feit is dat niemand eigenlijk weet hoeveel reserves er zijn en dat de gegevens die we hebben onbetrouwbaar zijn.quote:Peak-oil advocates remain unconvinced. A sign of depletion, they argue, is that big Western oil firms are finding it increasingly difficult to replace the oil they produce, let alone build their reserves. Art Smith of Herold, a consultancy, points to rising “finding and development” costs at the big firms, and argues that the world is consuming two to three barrels of oil for every barrel of new oil found. Michael Rodgers of PFC Energy, another consultancy, says that the peak of new discoveries was long ago. “We're living off a lottery we won 30 years ago,” he argues.

It is true that the big firms are struggling to replace reserves. But that does not mean the world is running out of oil, just that they do not have access to the vast deposits of cheap and easy oil that are left in Russia and members of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). And as the great fields of the North Sea and Alaska mature, non-OPEC oil production will probably peak by 2010 or 2015. That is soon—but it says nothing of what really matters, which is the global picture.

Argument is niet sound. Er mag dan volgens hun wel 3 trillion barrels nog te produceren olie zijn en nog mogelijkheden om onconventionele olie te produceren, maar de werkelijke vraag blijft kan dit binnen een redelijk korte termijn en is de productiecapaciteit groot genoeg om aan de vraag te voldoen.quote:When the United States Geological Survey (USGS) studied the matter closely, it concluded that the world had around 3 trillion barrels of recoverable conventional oil in the ground. Of that, only one-third has been produced. That, argued the USGS, puts the global peak beyond 2025. And if “unconventional” hydrocarbons such as tar sands and shale oil (which can be converted with greater effort to petrol) are included, the resource base grows dramatically—and the peak recedes much further into the future.

Leuk een aardig maar de vraag die ik hierboven stelde wordt niet beantwoord. Dit is alleen een statement van goed vertrouwen in de technologie.quote:It is also true that oilmen will probably discover no more “super-giant” fields like Saudi Arabia's Ghawar (which alone produces 5m bpd). But there are even bigger resources available right under their noses. Technological breakthroughs such as multi-lateral drilling helped defy predictions of decline in Britain's North Sea that have been made since the 1980s: the region is only now peaking.

Globally, the oil industry recovers only about one-third of the oil that is known to exist in any given reservoir. New technologies like 4-D seismic analysis and electromagnetic “direct detection” of hydrocarbons are lifting that “recovery rate”, and even a rise of a few percentage points would provide more oil to the market than another discovery on the scale of those in the Caspian or North Sea.

Further, just because there are no more Ghawars does not mean an end to discovery altogether. Using ever fancier technologies, the oil business is drilling in deeper waters, more difficult terrain and even in the Arctic (which, as global warming melts the polar ice cap, will perversely become the next great prize in oil). Large parts of Siberia, Iraq and Saudi Arabia have not even been explored with modern kit.

Alle reserves zijn speculatief. Dat gezegd hebbende ben ik het ook niet eens met die pessimisten. Zoals gezegd, er komen nog olievelden online en alternatieven zijn al in productie. Of dit echter op langere termijn (10 tot 15 jaar) nog genoeg is om aan de vraag te voldoen wanneer steeds meer velden minder produceren blijft de vraag.quote:The petro-pessimists' most forceful argument is that the Persian Gulf, officially home to most of the world's oil reserves, is overrated. Matthew Simmons, an American energy investment banker, argues in his book, “Twilight in the Desert”, that Saudi Arabia's oil fields are in trouble. In recent weeks a scandal has engulfed Kuwait, too. Petroleum Intelligence Weekly (PIW), a respected industry newsletter, got hold of government documents suggesting that Kuwait might have only half of the nearly 100 billion barrels in oil reserves that it claims (Saudi Arabia claims 260 billion barrels).