W&T Wetenschap & Technologie

Een plek om te discussiëren over wetenschappelijke onderwerpen, wetenschappelijke problemen, technologische projecten en grootse uitvindingen.

Ray Kurzweil @ Stanford University - 2006quote:"The Singularity" is a phrase borrowed from the astrophysics of black holes. The phrase has varied meanings; as used by Vernor Vinge and Raymond Kurzweil, it refers to the idea that accelerating technology will lead to superhuman machine intelligence that will soon exceed human intelligence, probably by the year 2030. The results on the other side of the "event horizon," they say, are unpredictable.

1. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9PWXrnsSrf0

2. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JSSYyFqpS3U

3. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HYIj3VxSdzI

http://www.aleph.se/Trans/Global/Singularity/singul.txt

http://www.aleph.se/Trans/Global/Singularity/sing.html

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technological_singularity

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Accelerating_change

[ Bericht 77% gewijzigd door Keromane op 29-01-2007 05:08:18 ]

kan je ff in een zin zeggen van singularity is?

want dat hele verhala met doemsenario's maakt het voor mij niet helemaal duidelijk.. en ik kan het ook wel zelf opzoeken, maar het lijkt me voor het topic ook handig

want dat hele verhala met doemsenario's maakt het voor mij niet helemaal duidelijk.. en ik kan het ook wel zelf opzoeken, maar het lijkt me voor het topic ook handig

In theorie vind ik iedereen aardig!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

In 1 zin: er wordt iets zo slim gemaakt, dat wij te dom worden en dus onnodig zijn voor dat slimme ding.

En dan dus niet een beetje slimmer, maar zoiets als een mier vs de mens. Factor 100.000 slimmer.

Ik overleef het echter, want als dat ding echt zo slim is komt ie niet op mijn kamer ik heb net een scheet gelaten.

En dan dus niet een beetje slimmer, maar zoiets als een mier vs de mens. Factor 100.000 slimmer.

Ik overleef het echter, want als dat ding echt zo slim is komt ie niet op mijn kamer ik heb net een scheet gelaten.

kijk das helderquote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:03 schreef Noin het volgende:

In 1 zin: er wordt iets zo slim gemaakt, dat wij te dom worden en dus onnodig zijn voor dat slimme ding.

En dan dus niet een beetje slimmer, maar zoiets als een mier vs de mens. Factor 100.000 slimmer.

Ik overleef het echter, want als dat ding echt zo slim is komt ie niet op mijn kamer ik heb net een scheet gelaten.

ben ik niet zo bang voor

In theorie vind ik iedereen aardig!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

Dus het enige (?) gevaar is dat de door de mens ontworpen technologie zo slim wordt dat het zich boven de mensheid verheft? Zolang het nog niet organisch is kan het weinig kwaad, lijkt me...

Het grote gevaar zit m wel in het toepassen van technieken, die door het vernuft ervan zo interessant zijn, dat er misschien niet voldoende over wordt nagedacht wat de implicaties zijn op de lange termijn. Zelfvernietiging is dan idd nabij. Daarbij natuurlijk ook logisch in de zin van logica; hoe sneller iets zich ontwikkelt (en oud wordt) hoe sneller het einde nabij is, tenzij je die weg kunt verlengen door maar door te blijven ontwikkkelen. Of niet?

Wel ultiem interessant btw!

Het grote gevaar zit m wel in het toepassen van technieken, die door het vernuft ervan zo interessant zijn, dat er misschien niet voldoende over wordt nagedacht wat de implicaties zijn op de lange termijn. Zelfvernietiging is dan idd nabij. Daarbij natuurlijk ook logisch in de zin van logica; hoe sneller iets zich ontwikkelt (en oud wordt) hoe sneller het einde nabij is, tenzij je die weg kunt verlengen door maar door te blijven ontwikkkelen. Of niet?

Wel ultiem interessant btw!

Je kunt:quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 15:54 schreef Angst het volgende:

kan je ff in een zin zeggen van singularity is?

1. vluchtig de eerste alinea's lezen

2. naar de video kijken

3. op een linkje van Wikipedia klikken

4. langer dan 0,1 seconde naar een van de grafiekjes kijken

of snel vergeten en verder spelen

Nee. Technological singularity is de harde limiet aan technologische vooruitgang, waarbij ontwikkelingen zo snel gaan dat de realiteit onvoorspelbaar wordt.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:03 schreef Noin het volgende:

In 1 zin: er wordt iets zo slim gemaakt, dat wij te dom worden en dus onnodig zijn voor dat slimme ding.

---

Bekijk gewoon die video's. Duidelijk uitgelegd en heel boeiend. Alleen al m.b.t. voorbeelden van technologie die je de komende tien jaar kunt verwachten.

Euh, dat is toch nu al? Toename van elektromagnetische golven, synthetische stoffen in voeding, etc.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:25 schreef Keromane het volgende:

-knip-

Nee. Technological singularity is de harde limiet aan technologische vooruitgang, waarbij ontwikkelingen zo snel gaan dat de realiteit onvoorspelbaar wordt.

-knip-

... of praat met Ramona, een AI bot op de site van Kurzweil.

http://www.kurzweilai.net

Meer over Kurzweil:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Kurzweil

http://www.kurzweilai.net

Meer over Kurzweil:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Raymond_Kurzweil

Op de Nederlandse wiki-pagina (klik mij) wordt het misschien duidelijker uitgelegd.

Ik geloof er zelf trouwens niet in. Er zijn bij technologie-ontwikkelingen ook vele dempende factoren, zoals gedane investeringen en lock-in. Probeer als voorbeeld daarvan maar eens een succesvolle verbetering op Windows te maken, of een auto met een niet-benzine aandrijving. Je kan het verzinnen maar je vecht tegen extreem succesvolle en alomvertegenwoordigde systemen.

Daarnaast is het de maatschappij die een co-evolutionair patroon met technologie doormaakt. Mensen moeten aan nieuwe technologieen wennen, erin investeren. Ze moeten het ook willen. Op een gegeven moment vinden veel mensen een techniek 'goed genoeg'. 3D tv's zijn in het komende decennium waarschijnlijk mogelijk, maar men heeft momenteel nog de grootste moeite om HD-DVD en Blu-Ray te slijten...

Er is wel een speed-up geweest op veel vlakken, en die kan ook nog wel wat doorgaan. Dit is met name te danken aan de globalisatie denk ik. Elk land moet harder concurreren omdat je anders omver wordt gelopen. En dus wordt overal harder gewerkt, harder geinnoveerd, de kwaliteit verhoogd en kosten verlaagd, wat technologie immens bereikbaar maakt. Ik denk alleen dat dit, per technologie-gebied, zal afvlakken op het moment dat technieken stabiel en bewezen zijn. Met een verrekijker bekeken zie ik technologie als een lappendeken van vloeibare deelgebieden die stuk voor stuk 'uitkristalliseren' en aan elkaar 'vriezen'.

Internet en computers zijn nu nog in een 'vluchtig' gebied aangezien ze nog zo jong zijn, maar ook hier zie je al grote toepassingsgebieden die stabiel zijn en waar nog maar weinig revoluties plaatsvinden; puur stapsgewijze verder-ontwikkeling, maar da's hardly op weg zijn naar een singulariteit..

Diverse argumenten van Kaczynski resoneren wel bij mij, al is het grotendeels melodrama denk ik. Ik zelf ben wel gecharmeerd van de theorie van het sociaal constructivisme. Ik kan weinig argumenten bedenken waarom een samenleving de ontwikkeling nog verder zou willen versnellen. Ook de belangrijke actoren zoals technologievoortbrengers (willen rendement op hun investeringen, niet weer een revolutie) en wettenmakers (kunnen het nu al haast niet bijbenen) zullen op een gegeven moment bottlenecks worden...

Verder geloof ik zelf in een ander 'buzzword' namelijk Peak oil Dus ik moet uberhaupt allemaal maar zien of onze ontwikkeling wel monotoon opwaarts is

[ Bericht 0% gewijzigd door eleusis op 27-01-2007 16:44:45 ]

Ik geloof er zelf trouwens niet in. Er zijn bij technologie-ontwikkelingen ook vele dempende factoren, zoals gedane investeringen en lock-in. Probeer als voorbeeld daarvan maar eens een succesvolle verbetering op Windows te maken, of een auto met een niet-benzine aandrijving. Je kan het verzinnen maar je vecht tegen extreem succesvolle en alomvertegenwoordigde systemen.

Daarnaast is het de maatschappij die een co-evolutionair patroon met technologie doormaakt. Mensen moeten aan nieuwe technologieen wennen, erin investeren. Ze moeten het ook willen. Op een gegeven moment vinden veel mensen een techniek 'goed genoeg'. 3D tv's zijn in het komende decennium waarschijnlijk mogelijk, maar men heeft momenteel nog de grootste moeite om HD-DVD en Blu-Ray te slijten...

Er is wel een speed-up geweest op veel vlakken, en die kan ook nog wel wat doorgaan. Dit is met name te danken aan de globalisatie denk ik. Elk land moet harder concurreren omdat je anders omver wordt gelopen. En dus wordt overal harder gewerkt, harder geinnoveerd, de kwaliteit verhoogd en kosten verlaagd, wat technologie immens bereikbaar maakt. Ik denk alleen dat dit, per technologie-gebied, zal afvlakken op het moment dat technieken stabiel en bewezen zijn. Met een verrekijker bekeken zie ik technologie als een lappendeken van vloeibare deelgebieden die stuk voor stuk 'uitkristalliseren' en aan elkaar 'vriezen'.

Internet en computers zijn nu nog in een 'vluchtig' gebied aangezien ze nog zo jong zijn, maar ook hier zie je al grote toepassingsgebieden die stabiel zijn en waar nog maar weinig revoluties plaatsvinden; puur stapsgewijze verder-ontwikkeling, maar da's hardly op weg zijn naar een singulariteit..

Diverse argumenten van Kaczynski resoneren wel bij mij, al is het grotendeels melodrama denk ik. Ik zelf ben wel gecharmeerd van de theorie van het sociaal constructivisme. Ik kan weinig argumenten bedenken waarom een samenleving de ontwikkeling nog verder zou willen versnellen. Ook de belangrijke actoren zoals technologievoortbrengers (willen rendement op hun investeringen, niet weer een revolutie) en wettenmakers (kunnen het nu al haast niet bijbenen) zullen op een gegeven moment bottlenecks worden...

Verder geloof ik zelf in een ander 'buzzword' namelijk Peak oil Dus ik moet uberhaupt allemaal maar zien of onze ontwikkeling wel monotoon opwaarts is

[ Bericht 0% gewijzigd door eleusis op 27-01-2007 16:44:45 ]

Ik in een aantal worden omschreven: Ondernemend | Moedig | Stout | Lief | Positief | Intuïtief | Communicatief | Humor | Creatief | Spontaan | Open | Sociaal | Vrolijk | Organisator | Pro-actief | Meedenkend | Levensgenieter | Spiritueel

Helaas vergeet je bij dit "doemscenario" te vermelden dat er een behoorlijke kans is dat die exponentieel toenemende computer intelligentie direct geintegreerd zal worden met onze eigen natuurlijke verschijningsvorm (die grijze massa), waarmee wij als collectief de borg queen anno 2100 reeds ver voorbij gestreefd zullen zijn. (Hopelijk ook ethisch.)

hak hout, haal water

Transhumanist, Piraat

Transhumanist, Piraat

iemand had het antwoord op mijn vraag gegeven, en ik heb de alinia's gelezen en ik snapte wel waar het over ging, maar niet waar de term signularity precies op sloegquote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:25 schreef Keromane het volgende:

[..]

Je kunt:

1. vluchtig de eerste alinea's lezen

2. naar de video kijken

3. op een linkje van Wikipedia klikken

4. langer dan 0,1 seconde naar een van de grafiekjes kijken

of snel vergeten en verder spelen

[..]

Nee. Technological singularity is de harde limiet aan technologische vooruitgang, waarbij ontwikkelingen zo snel gaan dat de realiteit onvoorspelbaar wordt.

---

Bekijk gewoon die video's. Duidelijk uitgelegd en heel boeiend. Alleen al m.b.t. voorbeelden van technologie die je de komende tien jaar kunt verwachten.

ik hoop dat verder zich niemand aan mijn post stoorde.

In theorie vind ik iedereen aardig!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

Bingo. Nee, wel benaderen we de limiet en we zien steeds meer dingen die erop wijzen.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:30 schreef Kjew het volgende:

[..]

Euh, dat is toch nu al? Toename van elektromagnetische golven, synthetische stoffen in voeding, etc.

Electromagnetische golven doen niet veel, die zijn er van nature al. Anders wordt het als golven je brein afscannen. In de video worden concrete voorbeelden gegeven dat de wetenschap al heel ver is met brainscans is. Afzonderlijke verbindingen kunnen nu al in kaart worden gebracht, live. Kennis van de hersenen is met sprongen vooruitgegaan.

Voor synthetische stoffen geldt zowat hetzelfde. Het gaat in de aanloop naar singularity niet meer om stofjes die invloed kunnen hebben maar om technologie. Nanotechnologie. Ook hiervan concrete voorbeelden van zaken die 7 jaar geleden nog toekomstmuziek waren.

Kurzweil omschrijft singularity als het moment dat mens en machine letterlijk één worden. Dat kan vrij geruisloos en heel snel gaan, als we niet oppassen. Juist omdat je te maken hebt met een exponentiele schaal. Zelfverbeterende technologie die steeds meer functies overneemt en veel krachtiger is dan de mens maakt de mens tot de zwakste schakel. In zekere zin had de tweede reaguurder gelijk, maar dat is niet de essentie. En aan opsluiten op je kamertje heb je niet veel wanneer de wereld om je heen een artificeel superorganisme is geworden. Nu al kun je je niet onttrekken aan registratie en een verplichte pas met binnenkort RFID chip. Blijf je de rest van je leven op je kamer, je bent hoe dan ook afhankelijk.

Kurzweil pleit ervoor dat er goed wordt nagedacht over consequenties van uitvindingen en toepassingen. In feite zijn we in staat krachtige kunstmatige intelligentie te creeeren dat allerlei vraagstukken weet op te lossen, maar totaal buiten ons bevattingsvermogen en doelstellingen om. Daarbij sleutelt die theoretische kunstmatige intelligentie (samenwerking van allerlei technologieen) continu aan zichzelf om zich te verbeteren. Een ontwikkeling die in feite ook gewoon doorgaat op die exponentiele schaal die je overal tegenkomt. Puur omdat we het zo ontworpen en geprogrammeerd hebben, dan, zonder de consequenties serieus te nemen. Puur theoretisch zouden we een zielloze superlevensvorm hebben gecreeerd waarover we totaal geen controle meer hebben. Dit 'superwezen' zou overal om ons heen zijn, in onszelf zijn zelfs, en onze realiteit worden. Zolang we het nog zouden overleven. In het meest extreme geval.

Zover komt het niet. Langzaam begint nu te dagen dat singularity geen SF sprookje is, maar een logisch gevolg. Dat je de nadering van die singulariteit in tal van zaken ziet. Het zal onderwerp worden van maatschappelijke discussie, veel verder dan deelvragen of je wel of niet aan genen mag gesleuteld worden of dat het klimaat opwarmt. Vandaar dat ik het item even graag onder de aandacht bracht.

als iets er nu is er geen schiencefictionquote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:06 schreef Kjew het volgende:

Maar noem eens iets dat werkelijk verbazingwekkende sciencefiction is op dit moment?

maar bijv. beeldtelefoons (wat we nu hebben skype, bellen via msn) waren een kleine 30 jaar geleden nog science fiction volgens mij hoor

komt in elk geval in star trek voor

en zo geld dat voor heel veel computer dingen zoals ook multiplayer games

etc.

maar jah nu heet dat geen sciencefiction meer

fiction = niet echt

dat kan iets dus nooit zijn als het al bestaat

In theorie vind ik iedereen aardig!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

Het is op zich wel vreemd dat je als bezoeker van WFL niet weet wat een singulariteit is, maar aan de andere kant: zelfs vandale.nl geeft geen antwoordquote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:55 schreef Angst het volgende:

[..]

iemand had het antwoord op mijn vraag gegeven, en ik heb de alinia's gelezen en ik snapte wel waar het over ging, maar niet waar de term signularity precies op sloeg

ik hoop dat verder zich niemand aan mijn post stoorde.

Daar komt ook nog bij dat de term singulariteit oorspronkelijk een wetenschappelijk natuurverschijnsel omschrijft, dat zich niet aan bestaande natuurwetten houdt. Dat dit woord steeds meer wordt gebruikt om andere abnormaliteiten binnen een context aan te duiden, is redelijk nieuw.

Persoonlijk vind ik zelfs dat de term singulariteit in deze context eigenlijk ongepast is, omdat de grenslijn bij een exponentiele lijn in de wiskunde een andere naam heeft (kan er zelf even niet op komen )

hak hout, haal water

Transhumanist, Piraat

Transhumanist, Piraat

Ik doel op iets dat recent ontdekt is en tot kort daarvoor nog als onmogelijk werd beschouwd.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:06 schreef Kjew het volgende:

Maar noem eens iets dat werkelijk verbazingwekkende sciencefiction is op dit moment?

Computers aansturen met gedachten?quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:34 schreef Kjew het volgende:

[..]

Ik doel op iets dat recent ontdekt is en tot kort daarvoor nog als onmogelijk werd beschouwd.

Ik in een aantal worden omschreven: Ondernemend | Moedig | Stout | Lief | Positief | Intuïtief | Communicatief | Humor | Creatief | Spontaan | Open | Sociaal | Vrolijk | Organisator | Pro-actief | Meedenkend | Levensgenieter | Spiritueel

Het is geen kwestie van geloven. Technologische vooruitgang volgt heel strak een exponentiele schaal. Toepassing van technologie ook. Dat komt na duizenden jaren niet zomaar tot stilstand. De groei gaat alsmaar door, ook op dit moment. Dat zijn keiharde feiten. Lange tijd is de groei in technologische ontwikkeling traag gegaan, maar zo werkt het met een exponentiele schaal. We zijn nu op het moment dat de ultieme limiet concreet in zicht komt. Kijk naar de grafiek m.b.t. de Wet van Moore.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 16:39 schreef soylent het volgende:

Op de Nederlandse wiki-pagina (klik mij) wordt het misschien duidelijker uitgelegd.

Ik geloof er zelf trouwens niet in. Er zijn bij technologie-ontwikkelingen ook vele dempende factoren, zoals gedane investeringen en lock-in. Probeer als voorbeeld daarvan maar eens een succesvolle verbetering op Windows te maken, of een auto met een niet-benzine aandrijving. Je kan het verzinnen maar je vecht tegen extreem succesvolle en alomvertegenwoordigde systemen.

Voorbeelden kloppen niet. Sinds internet er is is het bijv. geen seconde uitgevallen, behalve zeer plaatselijk en tijdelijk. Het gaat in singularity niet om een complex in elkaar geknutseld systeem of om geavanceerde produkten waar al dan niet een markt voor is, maar om netwerken met op zich zeer eenvoudige deelsystemen in combinatie met puur natuurlijke wetmatigheden. Kunstmatige intelligentie die zelf doelen gaat bepalen omdat we het zo ontworpen hebben. (*)

Neem de moeite om die lezing te bekijken. Wat je met die verrekijker ziet klopt, alleen vriest er nergens iets vast. Technologieen vloeien meer en meer in elkaar over en worden steeds vloeibaarder.

Inderdaad, er zijn weinig argumenten waarom je ontwikkelingen nog verder zou willen versnellen. Dat is de hamvraag. Realiteit is dat die versnellende versnelling gewoon plaatsvindt als een puur onbewust proces.

(*) Over 'Windows verbeteren' gesproken, ook Microsoft is bezig om hun systemen te verbeteren. Driemaal raden hoe ze het project noemen, al is het puur toeval. Hoop ik. ;-) Driemaal raden wat de essentie is van de research.

A Singularity application specifies which libraries it needs, and the Bartok compiler brings together the code and eliminates unneeded functionality through a process called "tree shaking," which deletes unused classes, methods, and even fields.

Plug-ins in Singularity execute in their own processes and communicate with carefully verified communication channels. Plug-ins can fail without killing the other. This architecture is practical because Singularity processes are inexpensive to create and communicate between since they rely on language safety, not virtual memory hardware, to enforce isolation.

Real time software engineering, zelfreplicatie, een prille vorm van AI in de absolute elementen van het systeem.

Is dat mogelijk?quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:35 schreef soylent het volgende:

[..]

Computers aansturen met gedachten?

In hoeverre?

Tja, geloven versus feiten.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:38 schreef Keromane het volgende:

[..]

Het is geen kwestie van geloven. Technologische vooruitgang volgt heel strak een exponentiele schaal. Toepassing van technologie ook. Dat komt na duizenden jaren niet zomaar tot stilstand. De groei gaat alsmaar door, ook op dit moment. Dat zijn keiharde feiten. Lange tijd is de groei in technologische ontwikkeling traag gegaan, maar zo werkt het met een exponentiele schaal. We zijn nu op het moment dat de ultieme limiet concreet in zicht komt. Kijk naar de grafiek m.b.t. de Wet van Moore.

Feiten moet je ook geloven (accepteren als waar / bewezen).

De bedenker van Technological singularity gelooft denk ik te veel in de korte termijn kennis die de laatste 20 jaar is opgedaan en baseert daar zijn grafiek op, zonder oog te hebben voor lange termijn natuur processen.

De ontwikkelingen in de tijd van de grieken en romeinen zijn uiteindelijk ook overschaduwd door de daarop volgende middeleeuwen.

Als je een lijntje trek met nu als eindpunt lijkt de lijn inderdaad exponentieel, maar als ik accepteer dat de natuur uiteindelijk een balans houdend karakter heeft, zal de wet van more geen stand houden.

Dan wordt als ik dit het lijntje over duizend jaar door trek de huidige stijging slechts een klein hobbeltje, gevolgd door een daling.

hak hout, haal water

Transhumanist, Piraat

Transhumanist, Piraat

Ik heb me vroeger een tijdje beziggehouden met Artificiele Intelligentie, maar ik ben er op een gegeven moment maar mee gestopt want m'n computer deed niet meer wat ik wilde.

Ik moet ook denken aan de waarschuwingen tegen de automatisering in de begintijd van de computer. "Mensen zouden overbodig kunnen worden, iedereen werkeloos omdat de computer alles deed". De realiteit nu is echter dat mensen nog nooit zo druk zijn geweest, de computer ontnam geen werk van mensen, maar zorgde juist voor een heleboel extra werk, dat door de vergroting van mogelijkheden met de PC als een multifunctioneel instrument.

Ik moet ook denken aan de waarschuwingen tegen de automatisering in de begintijd van de computer. "Mensen zouden overbodig kunnen worden, iedereen werkeloos omdat de computer alles deed". De realiteit nu is echter dat mensen nog nooit zo druk zijn geweest, de computer ontnam geen werk van mensen, maar zorgde juist voor een heleboel extra werk, dat door de vergroting van mogelijkheden met de PC als een multifunctioneel instrument.

Huidige trend atmosf. CO2 Mauna Loa: 411 ppm ,10 jaar geleden: 387 ppm , 25 jaar geleden: 358 ppm

Dat is in feite ook de essentie. Niet de wiskundige limiet is het probleem. Ook gaat technologische ontwikkeling niet oneindig snel op dat moment. Ontwikkeling is altijd gebonden aan natuurwetten. Wel zouden ons vertrouwde wetmatigheden in het leven niet meer op hoeven te gaan omdat we de ontwikkelingen niet meer kunnen bijbenen. Geen ontwikkelingen die we zelf doen, maar die we laten doen.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:19 schreef alien8ed het volgende:

[..]

Daar komt ook nog bij dat de term singulariteit oorspronkelijk een wetenschappelijk natuurverschijnsel omschrijft, dat zich niet aan bestaande natuurwetten houdt.

Enfin, ik heb gezien dat het een aantal mensen interesseert en daar deed ik het voor. Niet zozeer om erover te gaan discussieren, ik heb er ook weinig aan toe te voegen.

Ja, ik denk het ook. Ook denk ik dat je nog steeds de video's niet hebt bekeken. En ik geloof dat je niet eens de moeite hebt genomen om te kijken over wie je het hebt.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:52 schreef alien8ed het volgende:

[..]

De bedenker van Technological singularity gelooft denk ik te veel in de korte termijn kennis die de laatste 20 jaar is opgedaan en baseert daar zijn grafiek op, zonder oog te hebben voor lange termijn natuur processen.

Kijk die video's nou eens van begin tot eind. Doe eens gek. Dan zul je zien dat die singularity met de huidige technologie al mogelijk is. Zelfs zonder nanotubetechnologie die binnenkort op de markt komt of zelfs quantumcomputers.

(c) wikipedia.quote:Kurzweil grew up in Queens, New York. In his youth, he was an avid consumer of science fiction literature. By the age of twelve he had written his first computer program. Shortly after his discovery of programming, he appeared on the CBS television program I've Got a Secret, where he performed a piano piece that was composed by a computer he had built. In 1968, at the age of twenty, he sold a company he created that matched high schoolers with prospective colleges by answering a 200 question survey. He earned a BS in Computer Science and Literature in 1970 from MIT.

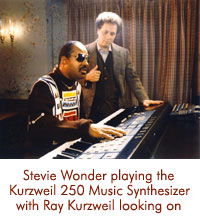

Kurzweil was the principal developer of the first omni-font optical character recognition system, the first print-to-speech reading machine for the blind, the first CCD flatbed scanner, the first text-to-speech synthesizer, the first electronic musical instrument capable of recreating the sound of a grand piano and other orchestral instruments (which he developed at the urging of Stevie Wonder, who was amazed by his OCR reading machine), and the first commercially marketed large-vocabulary speech recognition system.

He has founded nine businesses in the fields of OCR, music synthesis, speech recognition, reading technology, virtual reality, financial investment, medical simulation, and cybernetic art.

Kurzweil was inducted in 2002 into the National Inventors Hall of Fame, established by the United States Patent and Trademark Office. He received the $500,000 Lemelson-MIT Prize, the United States' largest award in invention and innovation, and the 1999 National Medal of Technology, the nation's highest honor in technology.

He has also received scores of other awards, including the 1994 Dickson Prize (Carnegie Mellon University's top science prize), Engineer of the Year from Design News, Inventor of the Year from MIT in 1998, the Association of American Publishers' award for the Most Outstanding Computer Science Book of 1990, and the Grace Murray Hopper Award from the Association for Computing Machinery and he received the Telluride Tech Festival Award of Technology in 2000.

He has received thirteen honorary doctorates, a 14th scheduled in 2007, and honors from three U.S. presidents.

He has been described as “the restless genius” by the Wall Street Journal, and “the ultimate thinking machine” by Forbes. Inc. magazine ranked him #8 among entrepreneurs in the United States, calling him the “rightful heir to Thomas Edison,” and PBS included Ray as one of sixteen “revolutionaries who made America” [1], along with other inventors of the past two centuries.

Kurzweil's musical keyboards company Kurzweil Music Systems produces among the most sophisticated and realistic (and expensive) synthesized-sound creation instruments. Ray sold Kurzweil Music Systems in the early 1990s to Korean piano manufacturer Young Chang. He has no current involvement with Young Chang or Kurzweil Music Systems.

Kurzweil has also created his own twenty five year old female rock star alter ego, "Ramona", who he regularly performs as through virtual reality technology [2] to illustrate the as-yet untapped possibilities of computers to enhance and alter our interpersonal interactions. This project inspired the plot of the movie S1m0ne.

In 2005, Microsoft chairman Bill Gates called Ray Kurzweil "the best at predicting the future of artificial intelligence".

Kurzweil has been associated with the National Federation of the Blind, many of whose members use his products. After speaking at their convention in 2005, he received a special award, an honor received by few sighted people.

He is on the Army Science Advisory Board and has testified before Congress on the subject of nanotechnology.

--

CV bekijken:

http://www.kurzweiltech.com/raycv.html

Bedrijven, uitvindingen, downloads, publicaties, demo's, etc:

http://www.kurzweiltech.com/companies_static.html

---

http://www.kurzweilai.net(...)elist.html?m=1%23664quote:Response to 'The Singularity Is Always Near'

by Ray Kurzweil

In "The Singularity Is Always Near," an essay in The Technium, an online "book in progress," author Kevin Kelly critiques arguments on exponential growth made in Ray Kurzweil's book, The Singularity Is Near. Kurzweil responds.

Published on KurzweilAI.net May 4, 2006

Allow me to clarify the metaphor implied by the term "singularity." The metaphor implicit in the term "singularity" as applied to future human history is not to a point of infinity, but rather to the event horizon surrounding a black hole. Densities are not infinite at the event horizon but merely large enough such that it is difficult to see past the event horizon from outside.

I say difficult rather than impossible because the Hawking radiation emitted from the event horizon is likely to be quantum entangled with events inside the black hole, so there may be ways of retrieving the information. This was the concession made recently by Hawking. However, without getting into the details of this controversy, it is fair to say that seeing past the event horizon is difficult (impossible from a classical physics perspective) because the gravity of the black hole is strong enough to prevent classical information from inside the black hole getting out.

We can, however, use our intelligence to infer what life is like inside the event horizon even though seeing past the event horizon is effectively blocked. Similarly, we can use our intelligence to make meaningful statements about the world after the historical singularity, but seeing past this event horizon is difficult because of the profound transformation that it represents.

So discussions of infinity are not relevant. You are correct that exponential growth is smooth and continuous. From a mathematical perspective, an exponential looks the same everywhere and this applies to the exponential growth of the power (as expressed in price-performance, capacity, bandwidth, etc.) of information technologies. However, despite being smooth and continuous, exponential growth is nonetheless explosive once the curve reaches transformative levels. Consider the Internet. When the Arpanet went from 10,000 nodes to 20,000 in one year, and then to 40,000 and then 80,000, it was of interest only to a few thousand scientists. When ten years later it went from 10 million nodes to 20 million, and then 40 million and 80 million, the appearance of this curve looks identical (especially when viewed on a log plot), but the consequences were profoundly more transformative. There is a point in the smooth exponential growth of these different aspects of information technology when they transform the world as we know it.

You cite the extension made by Kevin Drum of the log-log plot that I provide of key paradigm shifts in biological and technological evolution (which appears on page 17 of The Singularity Is Near). This extension is utterly invalid. You cannot extend in this way a log-log plot for just the reasons you cite. The only straight line that is valid to extend on a log plot is a straight line representing exponential growth when the time axis is on a linear scale and the a value (such as price-performance) is on a log scale. Then you can extend the progression, but even here you have to make sure that the paradigms to support this ongoing exponential progression are available and will not saturate. That is why I discuss at length the paradigms that will support ongoing exponential growth of both hardware and software capabilities. But it is not valid to extend the straight line when the time axis is on a log scale. The only point of these graphs is that there has been acceleration in paradigm shift in biological and technological evolution.

If you want to extend this type of progression, then you need to put time on a linear x axis and the number of years (for the paradigm shift or for adoption) as a log value on the y axis. Then it may be valid to extend the chart. I have a chart like this on page 50 of the book.

This acceleration is a key point. These charts show that technological evolution emerges smoothly from the biological evolution that created the technology creating species. You mention that an evolutionary process can create greater complexity—and greater intelligence—than existed prior to the process. And it is precisely that intelligence creating process that will go into hyper drive once we can master, understand, model, simulate, and extend the methods of human intelligence through reverse-engineering it and applying these methods to computational substrates of exponentially expanding capability.

That chimps are just below the threshold needed to understand their own intelligence is a result of the fact that they do not have the prerequisites to create technology. There were only a few small genetic changes, comprising a few tens of thousands of bytes of information, that distinguish us from our primate ancestors: a bigger skull (allowing a larger brain), a larger cerebral cortex, and a workable opposable appendage. There were a few other changes that other primates share to some extent such as mirror neurons and spindle cells

As I pointed out in my long now talk, a chimp's hand looks similar but the pivot point of the thumb does not allow facile manipulation of the environment. In contrast, our human ability to look inside the human brain and to model and simulate and recreate the processes we encounter there has already been demonstrated. The scale and resolution of these simulations will continue to expand exponentially. I make the case that we will reverse-engineer the principles of operation of the several hundred information processing regions of the human brain within about twenty years and then apply these principles (along with the extensive tool kit we are creating through other means in the AI field) to computers that will be many times (by the 2040s, billions of times) more powerful than needed to simulate the human brain.

You write that "Kurzweil found that if you make a very crude comparison between the processing power of neurons in human brains and the processing powers of transistors in computers, you could map out the point at which computer intelligence will exceed human intelligence." That is an oversimplification of my analysis. I provide in book four different approaches to estimating the amount of computation required to simulate all regions of the human brain based on actual functional recreations of brain regions. These all come up with answers in the same range, from 1014 to 1016 cps for creating a functional recreation of all regions of the human brain, so I've used 1016 cps as a conservative estimate.

This refers only to the hardware requirement. As noted above, I have an extensive analysis of the software requirements. While reverse-engineering the human brain is not the only source of intelligent algorithms (and, in fact, has not been a major source at all up until just recently because we did not have scanners that could see into the human with sufficient resolution until recently), my analysis of reverse-engineering the human brain is along the lines of an existence proof that we will have the software methods underlying human intelligence within a couple of decades.

Another important point in this analysis is that the complexity of the design of the human brain is about a billion times simpler than the actual complexity we find in the brain. This is due to the brain (like all biology) being a probabilistic recursively expanded fractal. This discussion goes beyond what I can write here (although it is in the book). We can ascertain the complexity of the design of the human brain because the design is contained in the genome and I show that the genome (including non-coding regions) only has about 30 to 100 million bytes of compressed information in it due to the massive redundancies in the genome.

So in summary, I agree that the singularity is not a discrete event. A single point of infinite growth or capability is not the metaphor being applied. Yes, the exponential growth of all facts of information technology is smooth, but is nonetheless explosive and transformative.

© 2006 Ray Kurzweil

OMG, is KurzweilAI dezelfde als Kurzweil van de synthesizers? Wat een held!

Nou vooruit Keromane, ik zal me erin verdiepen. Maar ik begin skeptisch!

Nou vooruit Keromane, ik zal me erin verdiepen. Maar ik begin skeptisch!

Ik in een aantal worden omschreven: Ondernemend | Moedig | Stout | Lief | Positief | Intuïtief | Communicatief | Humor | Creatief | Spontaan | Open | Sociaal | Vrolijk | Organisator | Pro-actief | Meedenkend | Levensgenieter | Spiritueel

In De Achterblijver van Yves Petry wordt het juist als redding gezien in plaats van een probleem.

Of althans een soortgelijk iets.

Of althans een soortgelijk iets.

Over een kwartier begint star gate, maar ik ga morgen je links wel ff bekijkenquote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 19:19 schreef Keromane het volgende:

[..]

Ja, ik denk het ook. Ook denk ik dat je nog steeds de video's niet hebt bekeken. En ik geloof dat je niet eens de moeite hebt genomen om te kijken over wie je het hebt.

Kijk die video's nou eens van begin tot eind. Doe eens gek. Dan zul je zien dat die singularity met de huidige technologie al mogelijk is. Zelfs zonder nanotubetechnologie die binnenkort op de markt komt of zelfs quantumcomputers.

[giga lap bewijsmateriaal]

Neemt echter niet weg dat hij wel degelijk zijn kennis baseert op kennis van de laatste twintig nou vooruit.... vijftig jaar....

He could still be wrong.

PS: ff voor de duidelijkheid:

Ik ontken niet dat er momenteel een enorme ontwikkeling plaats vind, die feiten spreken voor zich.

Ik betwijfel enkel dat dit tot een (dramatische) singulariteit moet leiden.

hak hout, haal water

Transhumanist, Piraat

Transhumanist, Piraat

Kweenie. Alhoewel ik nog maar één van de drie video's bekeken heb, vind ik hem niet echt overtuigend. Het gaat puur over technologie en niet zozeer over het tempo van de acceptatie in de samenleving. Ik heb de hele ontwikkeling van de personal computers meegemaakt en zal de laatste zijn om te ontkennen dat dit een spectaculaire en stormachtige ontwikkeling was. De laatste tijd bekruipt me echter een gevoel dat we de komende tijd steeds sterker de tweede wet van Gossen zullen gaan voelen. Dit is de wet van "het afnemende grensnut". Deze wet stelt dat als je honger hebt, de marginale boterham minder lekker smaakt dan de eerste. Dit is een bekende economische wet en geldt voor alles.

Ik zie mezelf als een "early adopter" van nieuwe technology en toch merk ik dat dit de laatste jaren minder wordt. Zo koop ik minder vaak een nieuwe PC dan vroeger, een grotere harddisk of een nog snellere videokaart. Games worden inderdaad realistischer (yep, heb een XBOX-360), maar de gameplay blijft redelijk hetzelfde en verveelt sneller (de eerste Halo versie maakte veel meer indruk). Ik hecht ook steeds minder waarde aan snellere datacom (zit nu op 7mbit/sec) en voor al mijn toepassingen voldoet het prima. In de jaren 90 wilde ik echter altijd het allernieuwste en stond ik kwijlend voor de etalage van de computer store (kan natuurlijk ook de leeftijd zijn...).

OK. Er komen terabyte-disks, 100Gb flash memorie drives, super HD DVD's, 100Ghz CPU's en terabyte ram chips, maar wat wordt de "killer" application die dat allemaal nuttig maakt?

Ik ben het daarom met een eerdere poster eens dat er genoeg tegenkrachten zullen zijn die voorkomen dat zo'n singulariteit gaat optreden in het tempo dat nu voorspeld wordt.

P.S.

Ik wil wel de Apple I-phone hebben !

Ik zie mezelf als een "early adopter" van nieuwe technology en toch merk ik dat dit de laatste jaren minder wordt. Zo koop ik minder vaak een nieuwe PC dan vroeger, een grotere harddisk of een nog snellere videokaart. Games worden inderdaad realistischer (yep, heb een XBOX-360), maar de gameplay blijft redelijk hetzelfde en verveelt sneller (de eerste Halo versie maakte veel meer indruk). Ik hecht ook steeds minder waarde aan snellere datacom (zit nu op 7mbit/sec) en voor al mijn toepassingen voldoet het prima. In de jaren 90 wilde ik echter altijd het allernieuwste en stond ik kwijlend voor de etalage van de computer store (kan natuurlijk ook de leeftijd zijn...).

OK. Er komen terabyte-disks, 100Gb flash memorie drives, super HD DVD's, 100Ghz CPU's en terabyte ram chips, maar wat wordt de "killer" application die dat allemaal nuttig maakt?

Ik ben het daarom met een eerdere poster eens dat er genoeg tegenkrachten zullen zijn die voorkomen dat zo'n singulariteit gaat optreden in het tempo dat nu voorspeld wordt.

P.S.

Ik wil wel de Apple I-phone hebben !

Your mind is like a parachute, it works best when it's open...

@Keromane: Vernor Vinge heeft ook 't nodige geschreven over de singulariteit.

I'm trying to make the 'net' a kinder, gentler place. One where you could bring the fuckin' children.

Dat slaat helemáál nergens op, het niet weten wat iets betekent heeft helemaal niets te maken met of je hier vaak komt of niet. Ik weet zeker dat er ook wel duizend voorbeelden zijn van dingen waar jij niets van weet en de gemiddelde WFL bezoeker wel.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:19 schreef alien8ed het volgende:

[..]

Het is op zich wel vreemd dat je als bezoeker van WFL niet weet wat een singulariteit is

O jawel.quote:

geeft ook meteen heel goed aan waarom ik niet zo vaak in WFL kom: veel te veel kutkneuzen die alleen maar over een onderwerpje kunnen beppen. En dan ook nog geeneens het onderscheid tussen klok en klepel kunnen maken.

I'm trying to make the 'net' a kinder, gentler place. One where you could bring the fuckin' children.

Misschien, heel misschien, verklaart de singulariteit wel de Fermi Paradox.

I'm trying to make the 'net' a kinder, gentler place. One where you could bring the fuckin' children.

omdat ik een defenitie niet ken van een of ander wetenschappelijk fenomeen wat uit zijn verband wordt getrokken, sorry hoor, als je iemand een kneus vind vanwege beperkte woordenschatquote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 21:52 schreef gronk het volgende:

[..]

O jawel.

geeft ook meteen heel goed aan waarom ik niet zo vaak in WFL kom: veel te veel kutkneuzen die alleen maar over een onderwerpje kunnen beppen. En dan ook nog geeneens het onderscheid tussen klok en klepel kunnen maken.

ben je zelf misschien geen kneus maar wel erg kortzichtig

In theorie vind ik iedereen aardig!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

<a href="http://img170.exs.cx/img170/7325/img90181an.jpg" rel="nofollow" target="_blank">check mijn schilderij!</a>

Jagermaster alleen als ie bloed en bloedheet is!

@Alien8ed

Skeptisch zijn is een gezonde eigenschap.

Kurzweil baseert 'bevindingen' natuurlijk niet op 50 jaar, of domweg een paar puntjes. Bekijk die video's en lees wat ie precies te zeggen heeft. Het zal je helemaal duidelijk worden.

Tempo van acceptatie heeft er niks mee te maken. Als jij overmorgen een nieuwe telefoon koopt dan zit daar nieuwe technologie in. Geen ouwe rommel. Over tien jaar zitten er de chips van over tien jaar in.

Het gaat niet om een applicatie, het gaat om de bouwstenen. Die gaan een omnipresent neurologisch netwerk vormen met ongekende capaciteiten om te leren, keuzes te maken en zichzelf te verbeteren. Uit te breiden misschien zelfs.

Overigens is er ooit iemand geweest die zich afvroeg wat het nut was om meer dan pakweg 640Kb te alloceren voor het OS. Ene Bill Gates, toen ie met MS DOS bezig was. Het zou toch nergens voor nodig zijn. Wat later zag ie internet niet zitten. Er zijn mensen die gezworen hebben geen PC te kopen, toch niet nodig. Later gold dat voor een kleurenmonitor, een geluidskaart, internet, de mobiele telefoon. Het was allemaal nergens voor nodig. Het klopt, het is ook allemaal nergens voor nodig. Maar dat heeft de vooruitgang niet weerhouden.

Tot slot, de vlieger dat er nog dingen moeten worden uitgevonden en we vanzelf wel tegen een grens aanlopen gaat niet op. Met de huidige technologie, kennis en inzichten zijn we al zover. Juist daarom is singularity een belangrijk issue aan het worden. Niet alleen in technologisch opzicht, maar ook maatschappelijk.

Skeptisch zijn is een gezonde eigenschap.

Kurzweil baseert 'bevindingen' natuurlijk niet op 50 jaar, of domweg een paar puntjes. Bekijk die video's en lees wat ie precies te zeggen heeft. Het zal je helemaal duidelijk worden.

Bekijk ook de andere delen voor je een oordeel velt. Het gaat er niet om om mensen ergens van te 'overtuigen'. De lezing gaat over de huidige stand van techniek, actuele ontwikkelingen en wat dit alles impliceert wanneer het 'zomaar' wordt toegepast omdat het toegepast kan worden. Kurzweil laat concrete, werkende voorbeelden zien.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 19:54 schreef Agno_Sticus het volgende:

Kweenie. Alhoewel ik nog maar één van de drie video's bekeken heb, vind ik hem niet echt overtuigend. Het gaat puur over technologie en niet zozeer over het tempo van de acceptatie in de samenleving.

Tempo van acceptatie heeft er niks mee te maken. Als jij overmorgen een nieuwe telefoon koopt dan zit daar nieuwe technologie in. Geen ouwe rommel. Over tien jaar zitten er de chips van over tien jaar in.

Het gaat niet om een applicatie, het gaat om de bouwstenen. Die gaan een omnipresent neurologisch netwerk vormen met ongekende capaciteiten om te leren, keuzes te maken en zichzelf te verbeteren. Uit te breiden misschien zelfs.

Overigens is er ooit iemand geweest die zich afvroeg wat het nut was om meer dan pakweg 640Kb te alloceren voor het OS. Ene Bill Gates, toen ie met MS DOS bezig was. Het zou toch nergens voor nodig zijn. Wat later zag ie internet niet zitten. Er zijn mensen die gezworen hebben geen PC te kopen, toch niet nodig. Later gold dat voor een kleurenmonitor, een geluidskaart, internet, de mobiele telefoon. Het was allemaal nergens voor nodig. Het klopt, het is ook allemaal nergens voor nodig. Maar dat heeft de vooruitgang niet weerhouden.

Tot slot, de vlieger dat er nog dingen moeten worden uitgevonden en we vanzelf wel tegen een grens aanlopen gaat niet op. Met de huidige technologie, kennis en inzichten zijn we al zover. Juist daarom is singularity een belangrijk issue aan het worden. Niet alleen in technologisch opzicht, maar ook maatschappelijk.

Met de IBM XT PC kon je ook al prima tekstverwerken, daar is het grensnut al lang bereikt.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 19:54 schreef Agno_Sticus het volgende:

Kweenie. Alhoewel ik nog maar één van de drie video's bekeken heb, vind ik hem niet echt overtuigend. Het gaat puur over technologie en niet zozeer over het tempo van de acceptatie in de samenleving. Ik heb de hele ontwikkeling van de personal computers meegemaakt en zal de laatste zijn om te ontkennen dat dit een spectaculaire en stormachtige ontwikkeling was. De laatste tijd bekruipt me echter een gevoel dat we de komende tijd steeds sterker de tweede wet van Gossen zullen gaan voelen. Dit is de wet van "het afnemende grensnut". Deze wet stelt dat als je honger hebt, de marginale boterham minder lekker smaakt dan de eerste. Dit is een bekende economische wet en geldt voor alles.

Ik zie mezelf als een "early adopter" van nieuwe technology en toch merk ik dat dit de laatste jaren minder wordt. Zo koop ik minder vaak een nieuwe PC dan vroeger, een grotere harddisk of een nog snellere videokaart. Games worden inderdaad realistischer (yep, heb een XBOX-360), maar de gameplay blijft redelijk hetzelfde en verveelt sneller (de eerste Halo versie maakte veel meer indruk). Ik hecht ook steeds minder waarde aan snellere datacom (zit nu op 7mbit/sec) en voor al mijn toepassingen voldoet het prima. In de jaren 90 wilde ik echter altijd het allernieuwste en stond ik kwijlend voor de etalage van de computer store (kan natuurlijk ook de leeftijd zijn...).

OK. Er komen terabyte-disks, 100Gb flash memorie drives, super HD DVD's, 100Ghz CPU's en terabyte ram chips, maar wat wordt de "killer" application die dat allemaal nuttig maakt?

Ik ben het daarom met een eerdere poster eens dat er genoeg tegenkrachten zullen zijn die voorkomen dat zo'n singulariteit gaat optreden in het tempo dat nu voorspeld wordt.

P.S.

Ik wil wel de Apple I-phone hebben !

Verder kun je de lijn op het gebied van steeds snellere en goedkopere computers met meer geheugen etc. nog wel even doortrekken. Maar dit is eigenlijk helemaal niet interressant.

Waar het werkelijk om gaat is de kruisbestuiving van allerlei nieuwe technieken. In eerste instantie zullen dat nanotechnologie, biochemie en genetica zijn.

Producten en toepassingen die hieruit voortkomen zullen totaal niet lijken op wat we nu kennen.

Ook zal puur door de rekenkracht en het combineren van alle beschikbare kennis de AI barriere worden doorbroken, dwz. machines zullen zelfstandig in staat zijn verder onderzoek te doen en met steeds betere producten en steeds betere versies van zichzelf te komen.

Waar dat toe leidt is niet voorspelbaar.

Alleen het tempo zal steeds hoger worden, totdat de grenzen bereikt worden van de natuurwetten zoals lichtsnelheid en quantumeffecten. De singulariteit is dus geen mathematische, maar meer bij wijze van spreken.

Praktisch gezien betekent dit dat de mens zoals we die nu kennen ophoudt te bestaan.

Een andere mogelijkheid is dat er iets verschikkelijk fout gaat en de mensheid ophoudt te bestaan of alles terugkeert naar het stenen tijdperk

Exaudi orationem meam

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Als je nog niet gekeken had, Kurzweils' eigen AI bot Ramona is indrukwekkend. 'Intelligentie', als je daarover mag spreken, gaat met sprongen vooruit.

http://www.kurzweilai.net/index.html?flash=1

Meer online AI:

http://www.pandorabots.co(...)c44735f5~/mostactive

I-God :

http://www.titane.ca/concordia/dfar251/igod/

http://www.kurzweilai.net/index.html?flash=1

Meer online AI:

http://www.pandorabots.co(...)c44735f5~/mostactive

I-God :

http://www.titane.ca/concordia/dfar251/igod/

Wacht ff. Je gaat nu wel erg kort door de bocht. Even samenvatten wat je zegt:quote:Op zondag 28 januari 2007 05:01 schreef Oud_student het volgende:

[..]

Met de IBM XT PC kon je ook al prima tekstverwerken, daar is het grensnut al lang bereikt.

Verder kun je de lijn op het gebied van steeds snellere en goedkopere computers met meer geheugen etc. nog wel even doortrekken. Maar dit is eigenlijk helemaal niet interressant.

Waar het werkelijk om gaat is de kruisbestuiving van allerlei nieuwe technieken. In eerste instantie zullen dat nanotechnologie, biochemie en genetica zijn.

Producten en toepassingen die hieruit voortkomen zullen totaal niet lijken op wat we nu kennen.

Ook zal puur door de rekenkracht en het combineren van alle beschikbare kennis de AI barriere worden doorbroken, dwz. machines zullen zelfstandig in staat zijn verder onderzoek te doen en met steeds betere producten en steeds betere versies van zichzelf te komen.

Waar dat toe leidt is niet voorspelbaar.

Alleen het tempo zal steeds hoger worden, totdat de grenzen bereikt worden van de natuurwetten zoals lichtsnelheid en quantumeffecten. De singulariteit is dus geen mathematische, maar meer bij wijze van spreken.

Praktisch gezien betekent dit dat de mens zoals we die nu kennen ophoudt te bestaan.

Een andere mogelijkheid is dat er iets verschikkelijk fout gaat en de mensheid ophoudt te bestaan of alles terugkeert naar het stenen tijdperk

1. de kruisbestuiving van nanotechnologie, biochemie en genetica is waar het werkelijk om gaat...

2. waar dat toe leidt is niet voorspelbaar...

3. De AI barriere wordt doorbroken, machines worden zelfstandig en maken betere versies van zichzelf.

4. de grenzen van de natuurwetten zoals lichtsnelheid en quantumeffecten zullen bereikt worden...

5. praktisch gezien betekent dit dat de mens zoals we die nu kennen ophoudt te bestaan...

Het klinkt allemaal zo "hijgerig" en "van wij zieners hebben het licht al gezien" of "je moet alle filmpjes kijken, dan piep wel anders". Krijg hierdoor eerder de neiging om juist het tegenovergestelde te gaan beweren. Daarom dit provocatief tegengeluid

Het zijn volgens mij precies dezelfde voorspellingen uit de wat oudere SF literatuur over het jaar 2000.Ik zie echter nog altijd niets om mij heen wat me op een "science fiction" achtige manier verbaast, het meeste is een extrapolatie van bestaande functionaliteit (bijv. een snellere PC, hogere bandbreedte, "user seductive" gebruikers interface, kleinere en draadloze telefoon, etc.). Het blijven echter allemaal dezelfde basisprincipes, alleen worden ze steeds kleiner en sneller. De natuurkundige grenzen komen echter wel in zicht. Op natuurkundig gebied lijkt de vooruitgang tegenwoordig zelfs vrij langzaam te gaan, zeker vergeleken met de schokgolven van vorige eeuw (relativeit uit begin 20ste eeuw, quantumfysica uit de jaren 20/30, standaardmodel uit de jaren 60, stringtheorie uit de jaren 80).

Een "beam me up Scotty" techniek zou me bijv. wel verbazen of een apparaat dat echt gedachten kan lezen. Zelfs het Internet was eigenlijk al een oud idee en is een heel logisch, simpel te begrijpen concept. Het is echter niet spectaculairder dan het feit dat er stroom, telefoon of een riolering op elk huis is aangesloten. OK, er zijn een heleboel leuke toepassingen te bedenken (zoals het FOK-forum ), de wereld is wat beter met elkaar verbonden, je kan sneller kennis vergaren, maar hoe dramatisch heeft dat ons nu eigenlijk veranderd? Licht en telefoon hebben waarschijnlijk een veel grotere gepercipieerde impact op de mens gehad. Een trend die me veel meer zorgen baart is de volgende. Het lijkt er op dat ons grensnut van nieuwe ontwikkelingen steeds verder afneemt en dat we er ook steeds minder door geraakt/verbaasd worden (behalve dan de Apple iPhone ). Ga maar eens na wat jouw laatste "flash bulb memory" ervaring was (Theo van Gogh was al minder dan bij Pim Fortuyn)

De nieuwe technologie stelt de mens ook nog eens in staat om zich individueler op te stellen (kijk maar eens in de trein: mp3 speler, koptelefoon, mobieltje + rayban donkere zonnebril om elk contact te vermijden) en hij/zij raakt daardoor sociaal geïsoleerd. Daarom geloof ik dat er een menselijke en meer sociale tegenbeweging op gang zal komen die kans op een technologische singularitiet sterk zal verminderen.

P.S.

Heb de typefout in de laatste zin expres laten zitten om aan te tonen hoe menselijk ik nog ben

Your mind is like a parachute, it works best when it's open...

Het lijkt mij logisch gezien wel de richting waar het heen gaat, of de mensheid/robotheid vernietigd zichzelf of er gebeurt een verschrikkelijk ongeluk.quote:Op zondag 28 januari 2007 18:12 schreef Agno_Sticus het volgende:

[..]

Wacht ff. Je gaat nu wel erg kort door de bocht. Even samenvatten wat je zegt:

1. de kruisbestuiving van nanotechnologie, biochemie en genetica is waar het werkelijk om gaat...

2. waar dat toe leidt is niet voorspelbaar...

3. De AI barriere wordt doorbroken, machines worden zelfstandig en maken betere versies van zichzelf.

4. de grenzen van de natuurwetten zoals lichtsnelheid en quantumeffecten zullen bereikt worden...

5. praktisch gezien betekent dit dat de mens zoals we die nu kennen ophoudt te bestaan...

Het klinkt allemaal zo "hijgerig" en "van wij zieners hebben het licht al gezien" of "je moet alle filmpjes kijken, dan piep wel anders". Krijg hierdoor eerder de neiging om juist het tegenovergestelde te gaan beweren. Daarom dit provocatief tegengeluid

Ik denk dat er naast de kwantitatieve vooruitgang en de extrapolatie van trends, steeds sneller, kleiner etc. ook een kwalitatieve vooruitgang gaat komen. Ik zie dat dan in de medische sector en en productie van nieuwe materialen gebaseerd op nanotechnologie.quote:Het zijn volgens mij precies dezelfde voorspellingen uit de wat oudere SF literatuur over het jaar 2000.Ik zie echter nog altijd niets om mij heen wat me op een "science fiction" achtige manier verbaast, het meeste is een extrapolatie van bestaande functionaliteit (bijv. een snellere PC, hogere bandbreedte, "user seductive" gebruikers interface, kleinere en draadloze telefoon, etc.). Het blijven echter allemaal dezelfde basisprincipes, alleen worden ze steeds kleiner en sneller. De natuurkundige grenzen komen echter wel in zicht. Op natuurkundig gebied lijkt de vooruitgang tegenwoordig zelfs vrij langzaam te gaan, zeker vergeleken met de schokgolven van vorige eeuw (relativeit uit begin 20ste eeuw, quantumfysica uit de jaren 20/30, standaardmodel uit de jaren 60, stringtheorie uit de jaren 80).

Ben ik gehel eens, wat we nu nog steeds zien is meer van hetzelfde maar dan sneller, goedkoper, kleiner etc. Ik zit idd niet te wachten op een mobieltje met nog kleienre toetsen en nog meer menus die ik niet gebruik. dat is geen innovatie, maar primitieve marketing.quote:Een "beam me up Scotty" techniek zou me bijv. wel verbazen of een apparaat dat echt gedachten kan lezen. Zelfs het Internet was eigenlijk al een oud idee en is een heel logisch, simpel te begrijpen concept. Het is echter niet spectaculairder dan het feit dat er stroom, telefoon of een riolering op elk huis is aangesloten. OK, er zijn een heleboel leuke toepassingen te bedenken (zoals het FOK-forum ), de wereld is wat beter met elkaar verbonden, je kan sneller kennis vergaren, maar hoe dramatisch heeft dat ons nu eigenlijk veranderd? Licht en telefoon hebben waarschijnlijk een veel grotere gepercipieerde impact op de mens gehad. Een trend die me veel meer zorgen baart is de volgende. Het lijkt er op dat ons grensnut van nieuwe ontwikkelingen steeds verder afneemt en dat we er ook steeds minder door geraakt/verbaasd worden (behalve dan de Apple iPhone ). Ga maar eens na wat jouw laatste "flash bulb memory" ervaring was (Theo van Gogh was al minder dan bij Pim Fortuyn)

Zo is het bijv. onvoorstelbaar dat een primitieve interface als SMS zo populair is. Waarom zouden de producenten iets anders maken als de massa tevreden is?

Toch ben ik ervan overtuigd dat er geheel nieuwe vindingen komen onafhankelijk van het feit of we er nu op zitten wachten of niet. Ze komen er omdat het mogelijk is (geworden)

Wat de effecten van de "singulariteit" zullen zijn is irrelevant en onvoorspelbaar.quote:De nieuwe technologie stelt de mens ook nog eens in staat om zich individueler op te stellen (kijk maar eens in de trein: mp3 speler, koptelefoon, mobieltje + rayban donkere zonnebril om elk contact te vermijden) en hij/zij raakt daardoor sociaal geïsoleerd. Daarom geloof ik dat er een menselijke en meer sociale tegenbeweging op gang zal komen die kans op een technologische singularitiet sterk zal verminderen.

Als mensen zich al met simpele middelen als internet en MP3 spelers zich individueel willen opstellen, dan worden de mogelijkheden hiervoor in de toekomst alleen maar uitgebreider en gesofisticeerder.

De mensheid zoals we die kennen zal eens ophouden te bestaan, of je het nu leuk vindt of niet. De technische ontwikkelingen kun je niet tegenhouden.quote:P.S.

Heb de typefout in de laatste zin expres laten zitten om aan te tonen hoe menselijk ik nog ben

Exaudi orationem meam

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine.

Et lux perpetua luceat eis.

Nah, dat denk ik niet. Wat me stukken waarschijnlijker lijkt is dat een gedeelte van de mensheid 'takes off', en een ander gedeelte blijft achter, op 'n berooide planeet, met restanten half-bruikbare technologie. De laatste groep zal waarschijnlijk na een jaar of tien, twintig terugvallen op 'n middeleeuws aandoende 'steady-state'.quote:Op zondag 28 januari 2007 18:36 schreef Oud_student het volgende:

De mensheid zoals we die kennen zal eens ophouden te bestaan, of je het nu leuk vindt of niet. De technische ontwikkelingen kun je niet tegenhouden.

Overigens, Vernor vinge (waar meneer kurzweil op vegeteert) gaf aan dat de periode 2010-2035 beslissend gaat worden; of de singulariteit wordt werkelijkheid, of de 'technologische revolutie' eindigt, en laat ons achter met een stel kleine, krachtige PC's en heel veel hulpmiddelen die productie eenvoudig maken.Steekwoord: 'intelligence amplification'.

I'm trying to make the 'net' a kinder, gentler place. One where you could bring the fuckin' children.

Dat samenzweerderige toontje maak jij ervan.quote:Op zondag 28 januari 2007 18:12 schreef Agno_Sticus het volgende:

of "je moet alle filmpjes kijken, dan piep wel anders".

Uit diverse reacties bleek dat men geen flauw idee had waarover het nu ging maar wel het antwoord klaar had en het al opzij wilde schuiven als de zoveelste onbelangrijke hoax. Vandaar dat ik erop aandrong om de lezing in z'n geheel te bekijken en stukken te lezen.

Singularity gaat niet om een hype of over doemscenario's. Het is de huidige staat van technologie, ontwikkelingen die in een stroomversnelling zitten en de maatschappelijke consequenties die dit heeft. Met de mogelijkheden die er nu al zijn moeten we met z'n allen goed nadenken wat we ermee doen. Gaan we alles doen wat mogelijk is? Gaan we onszelf als het ware volstoppen met technologie? Gaan we functies overdragen aan een hyperintelligente omnipresente AI?

Heel goed dat je gelooft dat er een 'tegenbeweging' op gang komt. Sterker nog, die is er al. Zoek eens op Kurzweil. ;-)

Kurzweil vegeteert nergens op. Het is normaal in de academische wereld dat je samenwerkt en voortbouwt. In de jaren 50 werd 'singularity' overigens al omschreven.quote:

Kurzweil wordt gezien als een van de belangrijkste intellectuelen van dit moment en heeft veel technologische innovaties op zijn naam staan. Muziekinstrumenten, (document)scanners, spraakherkenning, AI. Hij staat aan het hoofd van diverse adviescommissies, waaronder 'the singularity institute for artificial intelligence'. De summit op Stanford in 2006, waar de opname van is, was een internationaal wetenschappelijk congres.

http://sss.stanford.edu/

http://www.singinst.org/index.php

http://www.accelerating.org/

In de eerste posting stond overigens al een link naar een stuk van Vinge.

Nog wat interessante links:

http://metaverseroadmap.org/index.html

http://3pointd.com/

Laat die singularity maar komen, zolang het menselijkse aspect maar niet vergeten word.

Dat blijft toch het belangrijkste ondanks alle handige dingen die nog uitgvonden/verbeterd zullen worden.

Dat blijft toch het belangrijkste ondanks alle handige dingen die nog uitgvonden/verbeterd zullen worden.

Op zich lijkt me het heel handig om mijn computer met mijn gedachten te kunnen besturen. Sheelt weer lamme armen krijgen als je lang bezig bent.quote:Op zaterdag 27 januari 2007 17:35 schreef soylent het volgende:

[..]

Computers aansturen met gedachten?

Follow your heart and your dreams won't be far behind

Life is too short to wake up with regrets. So love the people who treat you right. Forget about the ones who don’t. If you get a second chance, grab it!

Life is too short to wake up with regrets. So love the people who treat you right. Forget about the ones who don’t. If you get a second chance, grab it!

Dit is een van de volgende stappen op roadmap internet :

http://www.planet.nl/plan(...)tid=806393/sc=7e0a3e

Second Life wordt overigens behoorlijk gehyped. Active Worlds was er al veel eerder en is technisch gezien beter. In de begintijd waren grote jongens zoals Philips erbij betrokken. De makers weten het alleen niet goed op de markt te zetten, het resultaat is een zee aan lege werelden.

Dat Google Earth meer functionaliteit krijgt -en VR aspiraties- is niet meer dan logisch. Een toekomstige versie van Google Earth zal je interface naar het web worden. Zowel op je desktop als op je PDA. Het HTML-based web krijgt een meer bibliotheekachtig karakter.

Webdesigners van nu kunnen zich maar vast bekwamen in 3D modelling en orienteren op GE based webservices/technologieen.

http://money.cnn.com/2006(...)ess2_futureboy_0511/

http://www.diskidee.nl/20(...)e-google-earth/7219/

http://www.planet.nl/plan(...)tid=806393/sc=7e0a3e

Second Life wordt overigens behoorlijk gehyped. Active Worlds was er al veel eerder en is technisch gezien beter. In de begintijd waren grote jongens zoals Philips erbij betrokken. De makers weten het alleen niet goed op de markt te zetten, het resultaat is een zee aan lege werelden.

Dat Google Earth meer functionaliteit krijgt -en VR aspiraties- is niet meer dan logisch. Een toekomstige versie van Google Earth zal je interface naar het web worden. Zowel op je desktop als op je PDA. Het HTML-based web krijgt een meer bibliotheekachtig karakter.

Webdesigners van nu kunnen zich maar vast bekwamen in 3D modelling en orienteren op GE based webservices/technologieen.

http://money.cnn.com/2006(...)ess2_futureboy_0511/

http://www.diskidee.nl/20(...)e-google-earth/7219/

Shakespear's "All the world is a stage" is veranderd in "all the world is a game"quote:Op zondag 28 januari 2007 20:40 schreef Keromane het volgende:

Dit is een van de volgende stappen op roadmap internet :

http://www.planet.nl/plan(...)tid=806393/sc=7e0a3e

Second Life wordt overigens behoorlijk gehyped. Active Worlds was er al veel eerder en is technisch gezien beter. In de begintijd waren grote jongens zoals Philips erbij betrokken. De makers weten het alleen niet goed op de markt te zetten, het resultaat is een zee aan lege werelden.

Dat Google Earth meer functionaliteit krijgt -en VR aspiraties- is niet meer dan logisch. Een toekomstige versie van Google Earth zal je interface naar het web worden. Zowel op je desktop als op je PDA. Het HTML-based web krijgt een meer bibliotheekachtig karakter.

Webdesigners van nu kunnen zich maar vast bekwamen in 3D modelling en orienteren op GE based webservices/technologieen.

http://money.cnn.com/2006(...)ess2_futureboy_0511/

http://www.diskidee.nl/20(...)e-google-earth/7219/

Maar of dit positief of negatief is weet ik nog niet....

Dat zal tijd ons leren (en dit zal inderdaad sneller gaan dan 100 jaar geleden)

Het geld dat altijd zo belangrijk is geweest om de economie te doen draaien, ging tot twintig jaar geleden grotendeels rond in de productieprocessen van deze wereld. Maar sinds de industrialisering en automatisering van deze processen de kosten dramatisch hebben doen kelderen, is er heel veel geld en tijd overgebleven. Deze tijd wordt door velen graag ingevuld met entertainment. Gamers en e-freaks leren tegenwoordig ontzettend veel skills in de nieuwe wereld.

Het sociaal, strategisch en tactisch inzicht van deze new-worlders is een totaal nieuwe vorm van cultuur en kennis, waar zeker een hele lichting van e-antropologen op losgelaten kan worden.

Ik hoop alleen dat we niet vergeten ook nog af en toe iets in de 'real world' te leren.

Want het risico dat we ons fysieke lichaam vergeten wordt realistischer, naar mate we meer en meer verdwaald raken in de online entertainment bizz.

Er zijn in Z-Korea al gamers overleden omdat ze dagen aan een stuk achter de PC zaten en hun lichaam dit niet meer aan kon.

hak hout, haal water

Transhumanist, Piraat

Transhumanist, Piraat

Hoho. Je onderschat nu al het gevaar van RBI ! (Repetitive Brain Injury).quote:Op zondag 28 januari 2007 20:21 schreef JediMasterLucia het volgende:

Op zich lijkt me het heel handig om mijn computer met mijn gedachten te kunnen besturen. Sheelt weer lamme armen krijgen als je lang bezig bent.

Your mind is like a parachute, it works best when it's open...

AI related

http://www.spiderland.org/download/breveIDE_windows_2.5.zip (1.2Mb)

"a 3d Simulation Environment for Multi-Agent Simulations and Artificial Life"

http://fbim.fh-regensburg(...)/diplom/e-index.html

Sample applet. Neural network AI

http://www.rennard.org/alife/english/antsgb.html

Ants. Plaats de nesten, de resources, maak obstakels.

http://www.frams.alife.pl/

Evolutie cyberorganismen in 3D.

Framsticks theater (verschilllende demo's)

Framsticks GUI (editor, simulator etc)

MPG filmpjes voorbeelden:

http://www.frams.alife.pl/common/purs_land1.mpg

http://www.frams.alife.pl/common/purs_water1.mpg

http://www.spiderland.org/download/breveIDE_windows_2.5.zip (1.2Mb)

"a 3d Simulation Environment for Multi-Agent Simulations and Artificial Life"

http://fbim.fh-regensburg(...)/diplom/e-index.html

Sample applet. Neural network AI

http://www.rennard.org/alife/english/antsgb.html

Ants. Plaats de nesten, de resources, maak obstakels.

http://www.frams.alife.pl/

Evolutie cyberorganismen in 3D.

Framsticks theater (verschilllende demo's)

Framsticks GUI (editor, simulator etc)

MPG filmpjes voorbeelden:

http://www.frams.alife.pl/common/purs_land1.mpg

http://www.frams.alife.pl/common/purs_water1.mpg

quote:These are safe bets, but they fail to capture the Web's disruptive trajectory. The real transformation under way is more akin to what Sun's John Gage had in mind in 1988 when he famously said, "The network is the computer." He was talking about the company's vision of the thin-client desktop, but his phrase neatly sums up the destiny of the Web: As the OS for a megacomputer that encompasses the Internet, all its services, all peripheral chips and affiliated devices from scanners to satellites, and the billions of human minds entangled in this global network. This gargantuan Machine already exists in a primitive form. In the coming decade, it will evolve into an integral extension not only of our senses and bodies but our minds.

Today, the Machine acts like a very large computer with top-level functions that operate at approximately the clock speed of an early PC. It processes 1 million emails each second, which essentially means network email runs at 1 megahertz. Same with Web searches. Instant messaging runs at 100 kilohertz, SMS at 1 kilohertz. The Machine's total external RAM is about 200 terabytes. In any one second, 10 terabits can be coursing through its backbone, and each year it generates nearly 20 exabytes of data. Its distributed "chip" spans 1 billion active PCs, which is approximately the number of transistors in one PC.

This planet-sized computer is comparable in complexity to a human brain. Both the brain and the Web have hundreds of billions of neurons (or Web pages). Each biological neuron sprouts synaptic links to thousands of other neurons, while each Web page branches into dozens of hyperlinks. That adds up to a trillion "synapses" between the static pages on the Web. The human brain has about 100 times that number—but brains are not doubling in size every few years. The Machine is.

Since each of its "transistors" is itself a personal computer with a billion transistors running lower functions, the Machine is fractal. In total, it harnesses a quintillion transistors, expanding its complexity beyond that of a biological brain. It has already surpassed the 20-petahertz threshold for potential intelligence as calculated by Ray Kurzweil. For this reason some researchers pursuing artificial intelligence have switched their bets to the Net as the computer most likely to think first. Danny Hillis, a computer scientist who once claimed he wanted to make an AI "that would be proud of me," has invented massively parallel supercomputers in part to advance us in that direction. He now believes the first real AI will emerge not in a stand-alone supercomputer like IBM's proposed 23-teraflop Blue Brain, but in the vast digital tangle of the global Machine.

In 10 years, the system will contain hundreds of millions of miles of fiber-optic neurons linking the billions of ant-smart chips embedded into manufactured products, buried in environmental sensors, staring out from satellite cameras, guiding cars, and saturating our world with enough complexity to begin to learn. We will live inside this thing.

Today the nascent Machine routes packets around disturbances in its lines; by 2015 it will anticipate disturbances and avoid them. It will have a robust immune system, weeding spam from its trunk lines, eliminating viruses and denial-of-service attacks the moment they are launched, and dissuading malefactors from injuring it again. The patterns of the Machine's internal workings will be so complex they won't be repeatable; you won't always get the same answer to a given question. It will take intuition to maximize what the global network has to offer. The most obvious development birthed by this platform will be the absorption of routine. The Machine will take on anything we do more than twice. It will be the Anticipation Machine.

quote:And the most universal. By 2015, desktop operating systems will be largely irrelevant. The Web will be the only OS worth coding for. It won't matter what device you use, as long as it runs on the Web OS. You will reach the same distributed computer whether you log on via phone, PDA, laptop, or HDTV.

http://www.kurzweilai.net(...)s/art0629.html?m%3D1quote:And who will write the software that makes this contraption useful and productive? We will. In fact, we're already doing it, each of us, every day. When we post and then tag pictures on the community photo album Flickr, we are teaching the Machine to give names to images. The thickening links between caption and picture form a neural net that can learn. Think of the 100 billion times per day humans click on a Web page as a way of teaching the Machine what we think is important. Each time we forge a link between words, we teach it an idea. Wikipedia encourages its citizen authors to link each fact in an article to a reference citation. Over time, a Wikipedia article becomes totally underlined in blue as ideas are cross-referenced. That massive cross-referencing is how brains think and remember. It is how neural nets answer questions. It is how our global skin of neurons will adapt autonomously and acquire a higher level of knowledge.

The human brain has no department full of programming cells that configure the mind. Rather, brain cells program themselves simply by being used. Likewise, our questions program the Machine to answer questions. We think we are merely wasting time when we surf mindlessly or blog an item, but each time we click a link we strengthen a node somewhere in the Web OS, thereby programming the Machine by using it.

---

quote:The Singularity—a notion that’s crept into a lot of skiffy, and whose most articulate in-genre spokesmodel is Vernor Vinge—describes the black hole in history that will be created at the moment when human intelligence can be digitized. When the speed and scope of our cognition is hitched to the price-performance curve of microprocessors, our "prog-ress" will double every eighteen months, and then every twelve months, and then every ten, and eventually, every five seconds.

quote:Kurzweil believes in the Singularity. In his 1990 manifesto, "The Age of Intelligent Machines," Kurzweil persuasively argued that we were on the brink of meaningful machine intelligence. A decade later, he continued the argument in a book called The Age of Spiritual Machines, whose most audacious claim is that the world’s computational capacity has been slowly doubling since the crust first cooled (and before!), and that the doubling interval has been growing shorter and shorter with each passing year, so that now we see it reflected in the computer industry’s Moore’s Law, which predicts that microprocessors will get twice as powerful for half the cost about every eighteen months. The breathtaking sweep of this trend has an obvious conclusion: computers more powerful than people; more powerful than we can comprehend.

quote:So how do you know if the backed-up you that you’ve restored into a new body—or a jar with a speaker attached to it—is really you? Well, you can ask it some questions, and if it answers the same way that you do, you’re talking to a faithful copy of yourself.

Sounds good. But the me who sent his first story into Asimov’s seventeen years ago couldn’t answer the question, "Write a story for Asimov’s" the same way the me of today could. Does that mean I’m not me anymore?

Kurzweil has the answer.