WKN Weer, Klimaat en Natuurrampen

Lees alles over het onstuimige weer op onze planeet, volg orkanen en tornado's, zie hoe vulkanen uitbarsten en hoe Moeder Aarde beeft bij een aardbeving. Alles over de verwoestende kracht van onze planeet en tal van andere natuurverschijnselen.

Nog nooit zoveel broeikasgassen in ozonlaag

Een nieuw record: nog nooit bevonden zich zoveel broeikasgassen in de atmosfeer als in 2010. En ze nemen ook steeds sneller toe.

Dat blijkt uit een nieuw rapport van de World Meteorological Organization (WMO). “Zelfs als we erin zouden slagen om vanaf vandaag geen broeikasgassen meer uit te stoten – en dat is helemaal niet aan de orde – zouden ze nog decennialang in de atmosfeer hangen en onze planeet en ons klimaat aantasten,” vertelt Michel Jarraud namens WMO.

CO2

De onderzoekers namen diverse broeikasgassen onder de loep. Bijvoorbeeld koolstofdioxide (CO2). Dit goedje heeft de grootste invloed op ons klimaat. Sinds 1750 is de hoeveelheid CO2 in de atmosfeer met 39 procent gestegen. En tussen 2009 en 2010 steeg die hoeveelheid enorm sterk: namelijk met 2,3 ppm (deeltjes per miljoen). Er is nu sprake van 389 ppm. Dat is aanzienlijk meer dan voor het begin van de industriŽle revolutie: toen was er 10.000 jaar lang sprake van zo’n 280 ppm. Nog nooit bevond zich zoveel CO2 in de atmosfeer als nu.

Methaan

Een ander broeikasgas is methaan. Tussen 1999 en 2006 was de hoeveelheid methaan in de atmosfeer redelijk stabiel. Maar nu stijgt het weer. Hoe dat komt, is onduidelijk. Mogelijk komt methaan vrij door het smelten van permafrost. Onderzoek moet dat uitwijzen.

Lachgas

Maar de onderzoekers waarschuwen met name voor distikstofmonoxide, oftewel lachgas. De hoeveelheid lachgas in de atmosfeer is twintig procent groter dan voor de industriŽle revolutie en de impact ervan is op lange termijn vele malen groter dan die van CO2.

Belangrijkste reden voor het feit dat zich enorm veel broeikasgassen in de atmosfeer bevinden, zijn de verbranding van fossiele brandstoffen, de landbouw (en dan in het bijzonder het gebruik van kunstmest) en boskap. “Meer dan ooit moeten we de complexe en soms onverwachte interacties tussen broeikasgassen in de atmosfeer, de biosfeer en oceanen begrijpen,” meent Jarraud. WMO blijft dan ook onderzoek doen.

scientias.nl

Een nieuw record: nog nooit bevonden zich zoveel broeikasgassen in de atmosfeer als in 2010. En ze nemen ook steeds sneller toe.

Dat blijkt uit een nieuw rapport van de World Meteorological Organization (WMO). “Zelfs als we erin zouden slagen om vanaf vandaag geen broeikasgassen meer uit te stoten – en dat is helemaal niet aan de orde – zouden ze nog decennialang in de atmosfeer hangen en onze planeet en ons klimaat aantasten,” vertelt Michel Jarraud namens WMO.

CO2

De onderzoekers namen diverse broeikasgassen onder de loep. Bijvoorbeeld koolstofdioxide (CO2). Dit goedje heeft de grootste invloed op ons klimaat. Sinds 1750 is de hoeveelheid CO2 in de atmosfeer met 39 procent gestegen. En tussen 2009 en 2010 steeg die hoeveelheid enorm sterk: namelijk met 2,3 ppm (deeltjes per miljoen). Er is nu sprake van 389 ppm. Dat is aanzienlijk meer dan voor het begin van de industriŽle revolutie: toen was er 10.000 jaar lang sprake van zo’n 280 ppm. Nog nooit bevond zich zoveel CO2 in de atmosfeer als nu.

Methaan

Een ander broeikasgas is methaan. Tussen 1999 en 2006 was de hoeveelheid methaan in de atmosfeer redelijk stabiel. Maar nu stijgt het weer. Hoe dat komt, is onduidelijk. Mogelijk komt methaan vrij door het smelten van permafrost. Onderzoek moet dat uitwijzen.

Lachgas

Maar de onderzoekers waarschuwen met name voor distikstofmonoxide, oftewel lachgas. De hoeveelheid lachgas in de atmosfeer is twintig procent groter dan voor de industriŽle revolutie en de impact ervan is op lange termijn vele malen groter dan die van CO2.

Belangrijkste reden voor het feit dat zich enorm veel broeikasgassen in de atmosfeer bevinden, zijn de verbranding van fossiele brandstoffen, de landbouw (en dan in het bijzonder het gebruik van kunstmest) en boskap. “Meer dan ooit moeten we de complexe en soms onverwachte interacties tussen broeikasgassen in de atmosfeer, de biosfeer en oceanen begrijpen,” meent Jarraud. WMO blijft dan ook onderzoek doen.

scientias.nl

Ach wanneer de olie op is lost het probleem zich vanzelf op

Hoe meer broeikasgassen hoe beter voor de ozonlaag dus dat scheelt weer.

Hoe meer broeikasgassen hoe beter voor de ozonlaag dus dat scheelt weer.

Klopt, maar je hebt een seizoenschommeling, en in die jaarlijkse cyclus zijn we rond deze tijd van het jaar op het laagste punt. Als er een seizoencorrectie wordt uitgevoerd... dus de stijgende lijn zonder de jaarlijkse schommelingen, is er nu sprake van iets meer dan 392 ppm atmosf. CO2. (Mauna Loa)quote:Er is nu sprake van 389 ppm.

Huidige trend atmosf. CO2 Mauna Loa: 411 ppm ,10 jaar geleden: 387 ppm , 25 jaar geleden: 358 ppm

Trouwens ook een rare titel voor dat bericht. Het zou moeten zijn "nog nooit zoveel broeikasgassen in de "atmosfeer".

(PS. De kop is nu aangepast op scientas.nl)

[ Bericht 68% gewijzigd door barthol op 22-11-2011 14:35:26 ]

(PS. De kop is nu aangepast op scientas.nl)

[ Bericht 68% gewijzigd door barthol op 22-11-2011 14:35:26 ]

Huidige trend atmosf. CO2 Mauna Loa: 411 ppm ,10 jaar geleden: 387 ppm , 25 jaar geleden: 358 ppm

Ik vraag me af tot welke maximumwaarde de atmosferische CO2 zal stijgen voordat er weer een dalende trend te zien zal zijn. Dus niet de waardes die voorspeld worden voor 2100, maar het maximimum van de curve.

Nu is het 392 ppm, en in 2025 zal het waarschijnlijk ongeveer 420 ppm zijn. En nog steeds een stijgende lijn. Wat is te verwachten bij de traagheid waarmee de curve kan afbuigen. Rekening houdend met de groei van de wereldbevolking, de groei van de Aziatische Economien, de psychologie van hoe mensen zich zullen verzetten om het verworven uitstootgedrag te veranderen. Wat is reŽel om te verwachten?

Zal het stijgen tot 1000 ppm? 1500 ppm? 2000 ppm? of nog meer? Beneden de duizend ppm lijkt me niet meer realistisch om te verwachten.

Wat zal het maximum uiteindelijk worden? (los ervan dat wij die nu leven geen van allen dat maximum mee zullen maken.)

Nu is het 392 ppm, en in 2025 zal het waarschijnlijk ongeveer 420 ppm zijn. En nog steeds een stijgende lijn. Wat is te verwachten bij de traagheid waarmee de curve kan afbuigen. Rekening houdend met de groei van de wereldbevolking, de groei van de Aziatische Economien, de psychologie van hoe mensen zich zullen verzetten om het verworven uitstootgedrag te veranderen. Wat is reŽel om te verwachten?

Zal het stijgen tot 1000 ppm? 1500 ppm? 2000 ppm? of nog meer? Beneden de duizend ppm lijkt me niet meer realistisch om te verwachten.

Wat zal het maximum uiteindelijk worden? (los ervan dat wij die nu leven geen van allen dat maximum mee zullen maken.)

Huidige trend atmosf. CO2 Mauna Loa: 411 ppm ,10 jaar geleden: 387 ppm , 25 jaar geleden: 358 ppm

Tja, dat hangt natuurlijk helemaal af welke onconventionele fossiele voorraden we nog aan gaan boren. Gaan we alle teerzanden ontginnen? Gaan we alle shalegas en olie gebruiken? Gaan we ook alle diep gelegen kolenlagen gebruiken (gassificatie)? Wat gaan de ontstelbaar grote methaan hydraten onder de bodems van de oceanen doen als we de temperatuur opjagen naar 2 - 4 graden, enorme feedbacks? (methaan oxideert na verloop van tijd tot CO2). Dat zijn allemaal vragen die van grote invloed zijn op de uiteindelijke CO2 niveau's en bijbehorende opwarming/acidificatie.quote:Op woensdag 23 november 2011 01:27 schreef barthol het volgende:

Ik vraag me af tot welke maximumwaarde de atmosferische CO2 zal stijgen voordat er weer een dalende trend te zien zal zijn. Dus niet de waardes die voorspeld worden voor 2100, maar het maximimum van de curve.

Nu is het 392 ppm, en in 2025 zal het waarschijnlijk ongeveer 420 ppm zijn. En nog steeds een stijgende lijn. Wat is te verwachten bij de traagheid waarmee de curve kan afbuigen. Rekening houdend met de groei van de wereldbevolking, de groei van de Aziatische Economien, de psychologie van hoe mensen zich zullen verzetten om het verworven uitstootgedrag te veranderen. Wat is reŽel om te verwachten?

Zal het stijgen tot 1000 ppm? 1500 ppm? 2000 ppm? of nog meer? Beneden de duizend ppm lijkt me niet meer realistisch om te verwachten.

Wat zal het maximum uiteindelijk worden? (los ervan dat wij die nu leven geen van allen dat maximum mee zullen maken.)

Ik ben het met je eens dat 1000ppm nauwelijks nog te voorkomen is oftewel een verdriedubbeling van het CO2 niveau tov pre-industrieel.

Realclimate heeft er een stuk over geschreven.

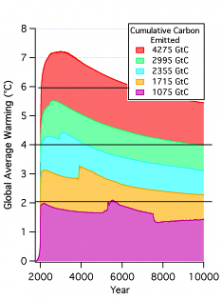

Het volgende plaatje geeft goed aan hoe lang onze acties nog een rol zullen blijven spelen. De krommes laten zien dat de temperatuur nog lang blijft stijgen nadat de emissies gestopt zijn:

Ook Archer 2005 doet een poging om de langetermijn effecten van de huidige fossiele brandstof verslaving in beeld te brengen:

Effect of fossil fuel CO2 on the future evolution of global mean temperature. Green represents natural evolution, blue represents the results of anthropogenic release of 300 Gton C, orange is 1000 Gton C, and red is 5000 Gton C

De kans is groot dat we de eerstvolgende echte ijstijd over zo'n 70-80.000 jaar zullen overslaan.

Paniekzaaierij of onderschat probleem?quote:Fountains of methane erupt in Arctic ice

The Russian research vessel Academician Lavrentiev conducted a survey of 10,000 square miles of sea off the coast of eastern Siberia.

They made a terrifying discovery - huge plumes of methane bubbles rising to the surface from the seabed.

'We found more than 100 fountains, some more than a kilometre across,' said Dr Igor Semiletov, 'These are methane fields on a scale not seen before. The emissions went directly into the atmosphere.'

Earlier research conducted by Semiletov's team had concluded that the amount of methane currently coming out of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf is comparable to the amount coming out of the entire world’s oceans.

Now Semiletov thinks that could be an underestimate.

The melting of the arctic shelf is melting 'permafrost' under the sea, which is releasing methane stored in the seabed as methane gas.

These releases can be larger and more abrupt than any land-based release. The East Siberian Arctic Shelf is a methane-rich area that encompasses more than 2 million square kilometers of seafloor in the Arctic Ocean.

'Earlier we found torch or fountain-like structures like this,' Semiletov told the Independent. 'This is the first time that we've found continuous, powerful and impressive seeping structures, more than 1,000 metres in diameter. It's amazing.'

'Over a relatively small area, we found more than 100, but over a wider area, there should be thousands of them.'

Semiletov's team used seismic and acoustic monitors to detect methane bubbles rising to the surface.

Scientists estimate that the methane trapped under the ice shelf could lead to extremely rapid climate change.

Current average methane concentrations in the Arctic average about 1.85 parts per million, the highest in 400,000 years. Concentrations above the East Siberian Arctic Shelf are even higher.

The shelf is shallow, 50 meters or less in depth, which means it has been alternately submerged or above water, depending on sea levels throughout Earth’s history.

During Earth’s coldest periods, it is a frozen arctic coastal plain, and does not release methane.

As the planet warms and sea levels rise, it is inundated with seawater, which is 12-15 degrees warmer than the average air temperature.

In deep water, methane gas oxidizes into carbon dioxide before it reaches the surface. In the shallows of the East Siberian Arctic Shelf, methane simply doesn’t have enough time to oxidize, which means more of it escapes into the atmosphere.

That, combined with the sheer amount of methane in the region, could add a previously uncalculated variable to climate models

De vrijkomst van methaan en bijhorende te verwachten stijging geeft een feedback effect waarmee de stijging autonoom wordt, dus ik zou dat wel als zorgwekkend opvatten ja.

|

|