F&L Filosofie & Levensbeschouwing

Een plek om te discussiŽren over filosofische vragen, filosofen, religieuze vraagstukken of religie en levensbeschouwing in het algemeen.

13-10-2014

Renť Descartes had tumor

Vandaag in 't kort: Renť Descartes had een tumor in zijn hoofd, er is een mozaÔekvloer in Griekenland gevonden, exotische slakken in de Oosterschelde en nieuwe supergladde coating.

© VisualForensic: Philippe Froesch/Isabelle Huynh-Charlier

De zeventiende-eeuwse filosoof Renť Descartes (1596-1650) had een flinke (goedaardige) tumor in zijn hoofd. Franse onderzoekers legden zijn schedel, die wordt bewaard in het Parijse Musťum national d’histoire naturelle, in een CT-scanner en vonden in de neusholte een verdikking van 3 bij 1.8 centimeter. Of de grondlegger van de moderne filosofie in zijn leven last had van de tumor is niet goed te zeggen. Veel voorkomende symptomen zijn onder andere hoofdpijn, een verstopte neus en verminderde reukzin, maar in biografieŽn van de Franse denker worden zulke aandoeningen niet genoemd. Het is bekend dat Descartes migraine had (en daarbij zelfs hallicuneerde), maar dat kan niet aan het gezwel toegeschreven worden. Ook zijn relatief vroege dood heeft zeer waarschijnlijk niets met de aandoening te maken.

In Noord-Griekenland is een mozaÔekvloer gevonden in een eeuwenoude graftombe. Het kunstwerk meet 3 bij 4,5 meter en bestaat uit blauwe, zwarte, witte en goudkleurige steentjes. In het midden is een grote beschadiging, maar die kan volgens de archeologen worden opgevuld met steentjes die bij het mozaÔek zijn gevonden. Het werk stamt uit de vierde eeuw voor Christus en beeldt de boodschapper-god Hermes af, die een man achter een span paarden begeleidt. De man zou Philippus II kunnen zijn, de vader van Alexander de Grote. Het graf behoort waarschijnlijk aan een familielid van Alexander, of een hoge generaal.

Foto: stichting Anemoon

De Oosterschelde heeft er een nieuwe bewoner bij: Aeolidiella sanguinea. De ‘verborgen vlokslak’, zoals het beestje in het Nederlands genoemd wordt, is een naaktzeeslak die nog niet eerder is waargenomen in de Zeeuwse wateren. Het is herkenbaar aan uitsteeksels op het lijf en de specifieke vorm van het eisnoer dat de slak afzet. De nieuwe slakkensoort is op eigen kracht van de West-Europese kust, via de Noordzee, de Oosterschelde binnengekomen.

Het is in Nederland dus een exoot: een diersoort die oorspronkelijk niet hier voorkomt. Het zal bij de slak niet direct zo’n vaart lopen, maar het komt vaak voor dat zulke invasieve soorten de biodiversiteit van een gebied ernstig aantasten. In Groot-BrittanniŽ wordt er bijvoorbeeld gevreesd voor een ‘Invasional meltdown’, vanwege oprukkende 'killer shrimps' (Dikerogammarus villosus) en Nederlandse mossels die de lokale soorten kunnen domineren.

Er is een nieuwe supergladde coating ontwikkeld, die zowel bloed- als bacterie-afstotend is. Het spul is bedoeld om medische apparatuur schoon te houden, en is zů glad dat zelfs gekko's er geen grip op hebben.

(npowetenschap.nl)

Renť Descartes had tumor

Vandaag in 't kort: Renť Descartes had een tumor in zijn hoofd, er is een mozaÔekvloer in Griekenland gevonden, exotische slakken in de Oosterschelde en nieuwe supergladde coating.

© VisualForensic: Philippe Froesch/Isabelle Huynh-Charlier

De zeventiende-eeuwse filosoof Renť Descartes (1596-1650) had een flinke (goedaardige) tumor in zijn hoofd. Franse onderzoekers legden zijn schedel, die wordt bewaard in het Parijse Musťum national d’histoire naturelle, in een CT-scanner en vonden in de neusholte een verdikking van 3 bij 1.8 centimeter. Of de grondlegger van de moderne filosofie in zijn leven last had van de tumor is niet goed te zeggen. Veel voorkomende symptomen zijn onder andere hoofdpijn, een verstopte neus en verminderde reukzin, maar in biografieŽn van de Franse denker worden zulke aandoeningen niet genoemd. Het is bekend dat Descartes migraine had (en daarbij zelfs hallicuneerde), maar dat kan niet aan het gezwel toegeschreven worden. Ook zijn relatief vroege dood heeft zeer waarschijnlijk niets met de aandoening te maken.

In Noord-Griekenland is een mozaÔekvloer gevonden in een eeuwenoude graftombe. Het kunstwerk meet 3 bij 4,5 meter en bestaat uit blauwe, zwarte, witte en goudkleurige steentjes. In het midden is een grote beschadiging, maar die kan volgens de archeologen worden opgevuld met steentjes die bij het mozaÔek zijn gevonden. Het werk stamt uit de vierde eeuw voor Christus en beeldt de boodschapper-god Hermes af, die een man achter een span paarden begeleidt. De man zou Philippus II kunnen zijn, de vader van Alexander de Grote. Het graf behoort waarschijnlijk aan een familielid van Alexander, of een hoge generaal.

Foto: stichting Anemoon

De Oosterschelde heeft er een nieuwe bewoner bij: Aeolidiella sanguinea. De ‘verborgen vlokslak’, zoals het beestje in het Nederlands genoemd wordt, is een naaktzeeslak die nog niet eerder is waargenomen in de Zeeuwse wateren. Het is herkenbaar aan uitsteeksels op het lijf en de specifieke vorm van het eisnoer dat de slak afzet. De nieuwe slakkensoort is op eigen kracht van de West-Europese kust, via de Noordzee, de Oosterschelde binnengekomen.

Het is in Nederland dus een exoot: een diersoort die oorspronkelijk niet hier voorkomt. Het zal bij de slak niet direct zo’n vaart lopen, maar het komt vaak voor dat zulke invasieve soorten de biodiversiteit van een gebied ernstig aantasten. In Groot-BrittanniŽ wordt er bijvoorbeeld gevreesd voor een ‘Invasional meltdown’, vanwege oprukkende 'killer shrimps' (Dikerogammarus villosus) en Nederlandse mossels die de lokale soorten kunnen domineren.

Er is een nieuwe supergladde coating ontwikkeld, die zowel bloed- als bacterie-afstotend is. Het spul is bedoeld om medische apparatuur schoon te houden, en is zů glad dat zelfs gekko's er geen grip op hebben.

(npowetenschap.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

16-10-2014

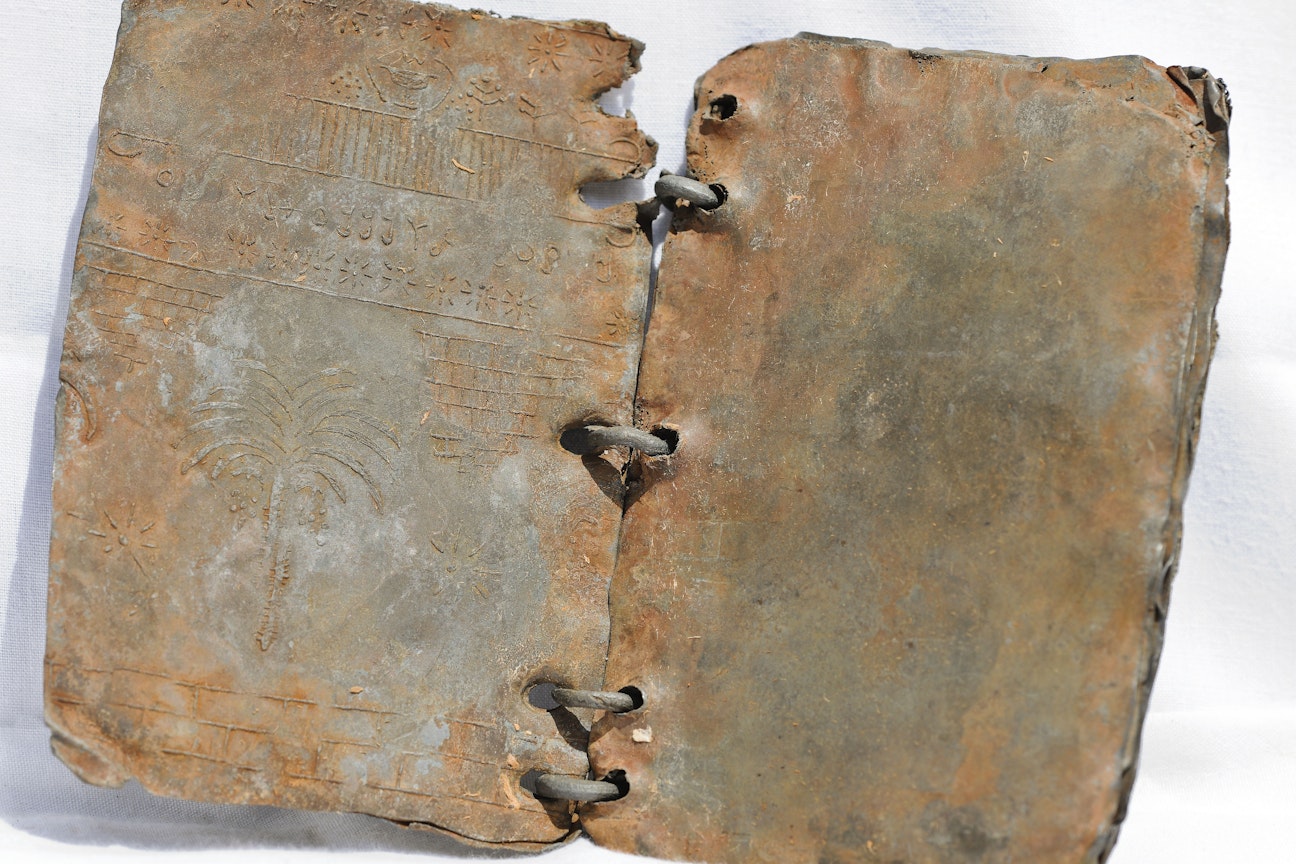

Bijbelrol bevat oudste officiŽle Bijbeltekst

Een Hebreeuwse Bijbelrol die al zeven jaar te zien is in het IsraŽl-museum in Jeruzalem, is het oudste handschrift met de officiŽle tekst van een deel van de Bijbel.

Foto: Thinkstock

Dat heeft Paul Sanders ontdekt, die als oudtestamenticus is verbonden aan de Protestantse Theologische Universiteit in Amsterdam. De rol bevat grote stukken uit Exodus, het tweede boek van het Oude Testament.

Sanders kwam het zogeheten Ashkar-Gilson-handschift op het spoor via de website van het museum. Hij raakte geÔnteresseerd, toen hij las dat de rol al in de 7e of 8e eeuw na Christus is geschreven.

Tot nu toe moesten Bijbelonderzoekers het doen met handschriften die uit de 10e eeuw of later stammen. Sanders belde naar het museum en toen hij hoorde dat nog niemand over de rol had geschreven, ging hij aan de slag.

Details

De oud-testamenticus is tot de conclusie gekomen dat de schrijvers die later de Hebreeuwse tekst van de Bijbel keer op keer overschreven, vermoedelijk van de Bijbelrol gebruik hebben gemaakt.

Het blijkt namelijk dat unieke details in de rol precies zo in latere handschriften voorkomen. Sanders heeft zijn bevindingen gepubliceerd in het gerenommeerde online tijdschrift Journal of Hebrew Scriptures.

Door: ANP

(nu.nl)

Bijbelrol bevat oudste officiŽle Bijbeltekst

Een Hebreeuwse Bijbelrol die al zeven jaar te zien is in het IsraŽl-museum in Jeruzalem, is het oudste handschrift met de officiŽle tekst van een deel van de Bijbel.

Foto: Thinkstock

Dat heeft Paul Sanders ontdekt, die als oudtestamenticus is verbonden aan de Protestantse Theologische Universiteit in Amsterdam. De rol bevat grote stukken uit Exodus, het tweede boek van het Oude Testament.

Sanders kwam het zogeheten Ashkar-Gilson-handschift op het spoor via de website van het museum. Hij raakte geÔnteresseerd, toen hij las dat de rol al in de 7e of 8e eeuw na Christus is geschreven.

Tot nu toe moesten Bijbelonderzoekers het doen met handschriften die uit de 10e eeuw of later stammen. Sanders belde naar het museum en toen hij hoorde dat nog niemand over de rol had geschreven, ging hij aan de slag.

Details

De oud-testamenticus is tot de conclusie gekomen dat de schrijvers die later de Hebreeuwse tekst van de Bijbel keer op keer overschreven, vermoedelijk van de Bijbelrol gebruik hebben gemaakt.

Het blijkt namelijk dat unieke details in de rol precies zo in latere handschriften voorkomen. Sanders heeft zijn bevindingen gepubliceerd in het gerenommeerde online tijdschrift Journal of Hebrew Scriptures.

Door: ANP

(nu.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

Randje R&P, wel.quote:We Are All Confident Idiots

An ignorant mind is precisely not a spotless, empty vessel, but one that’s filled with the clutter of irrelevant or misleading life experiences, theories, facts, intuitions, strategies, algorithms, heuristics, metaphors, and hunches that regrettably have the look and feel of useful and accurate knowledge.

This clutter is an unfortunate by-product of one of our greatest strengths as a species. We are unbridled pattern recognizers and profligate theorizers. Often, our theories are good enough to get us through the day, or at least to an age when we can procreate.

But our genius for creative storytelling, combined with our inability to detect our own ignorance, can sometimes lead to situations that are embarrassing, unfortunate, or downright dangerous—especially in a technologically advanced, complex democratic society that occasionally invests mistaken popular beliefs with immense destructive power (See: crisis, financial; war, Iraq).

As the humorist Josh Billings once put it, “It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.” (Ironically, one thing many people “know” about this quote is that it was first uttered by Mark Twain or Will Rogers—which just ain’t so.)

Vůůr het internet dacht men dat de oorzaak van domheid een gebrek aan toegang tot informatie was. Inmiddels weten we beter.

18-11-2014

Computermodel voorspelt strenge goden

In culturen die moeten overleven in een ruig klimaat waar het moeilijk is om aan voedsel te komen, geloven mensen in strengere, persoonlijke goden. Dat is een verschijnsel dat religiewetenschappers al lang kenden, maar nu is het ook nog eens bevestigd door… een computermodel.

door Maarten Muns

‘JHWH’, de god van het Jodendom, is een van de oudste en strengste goden ter wereld.

wikimedia commons

In de loop van de geschiedenis hebben mensen uiteenlopende soorten goden vereerd. Als je dat van een flinke afstand bekijkt zijn die goden in twee categorieŽn in te delen. Aan de ene kant staan afstandelijke goden, die de wereld geschapen hebben maar zich er verder niet meer mee bemoeien. Ze oordelen niet en houden zich nauwelijks met het leven van mensen bezig. Natuurgoden uit Afrika bijvoorbeeld.

Aan de andere kant bestaan goden die de wereld geschapen hebben en zich er regelmatig tegenaan bemoeien. Deze andere soort zijn strenge, persoonlijke goden. Mensen zijn aan hen verantwoording schuldig en met mensen die zich niet aan bepaalde regels houden kan het wel eens verkeerd aflopen. Een voorbeeld is de god van het Jodendom of bepaalde godsopvattingen binnen het christendom. Binnen deze twee extremen bestaan uiteraard heel veel tussenvormen.

Waar komen al die verschillende soorten goden vandaan? Waarom vereert de ene cultuur een strenge, persoonlijke god vereert en ziet de andere meer in een afstandelijke natuurgod? Dat is een discussie waar religiewetenschappers zich mee bezig houden. Dat strenge, persoonlijke goden vaker opduiken in samenlevingen die een hogere mate van politieke hiŽrarchie en sociale complexiteit hebben is al langer bekend. Een complexe samenleving heeft immers regels nodig, en het geloof in een strenge god die toeziet op die regels is een goed bindmiddel voor zo’n samenleving.

Onvriendelijke omgeving

Maar hoe zit het met ecologische factoren? Een ruiger klimaat leidt immers sneller tot complexe organisatie. Zou er dan ook een verband zijn tussen klimaat en godsbeleving? Het ligt voor de hand, maar is moeilijk aan te tonen. Om dat toch uit te zoeken maakten Amerikaanse evolutionair biologen een computerprogramma. Daarmee brachten ze de factoren in kaart die invloed hebben op de keuze voor een strenge dan wel afstandelijke god. De resultaten beschreven ze in wetenschappelijk tijdschrift PNAS.

In de uitkomst van het computermodel zijn de blauwe stipjes samenlevingen die een strenge, wetgevende god kennen. De rode stipjes kennen die niet. Op de onderliggende kaart zijn ecologische gegevens verwerkt. Wetgevende goden kwamen meer voor op plaatsen waar van nature minder ecologische variatie voorkomt (hoe grijzer het gebied, hoe meer ecologische variatie).

PNAS

De Amerikanen onderzochten de godsbeleving van groot aantal (historische) samenlevingen wereldwijd en vergeleken dat met gegevens over zaken als klimaat, temeratuurvariaties, aanwezigheid van wilde dieren en de beschikbaarheid van voedsel. Er bleek, zoals verwacht, inderdaad een sterk verband te zijn tussen de aanwezigheid van een strenge godheid en politieke complexiteit. Ook was volgens het computermodel de kans op een strenge god groter in samenlevingen die minder toegang tot water en voedsel hebben en in samenlevingen die in een veranderlijk en ruig klimaat leefden. De invloed van verschillende factoren werd zo duidelijk. Er lijkt een duidelijk verband uit het model te komen: In een ruig klimaat ontstaan strenge goden. Het model kon het soort god dat ergens zou ontstaan met 91% zekerheid voorspellen.

Een gedeeld geloof in een persoonlijke god kan helpen angst weg te nemen en zodoende een samenleving beter in staat stellen te overleven in een gevaarlijke en onvriendelijke omgeving. Het is voor het eerst dat een verband tussen ecologie en religie op deze manier aangetoond is. Laten complexe historische en culturele ontwikkelingen zich echt op deze manier verklaren? Niet volledig, want elke situatie is uniek en moet afzonderlijk onderzocht worden om per geval iets zinnigs te kunnen zeggen. Maar computermodellen kunnen geesteswetenschappers wel helpen met overzicht krijgen in moeilijke culturele en historische vraagstukken.

(Kennislink)

Computermodel voorspelt strenge goden

In culturen die moeten overleven in een ruig klimaat waar het moeilijk is om aan voedsel te komen, geloven mensen in strengere, persoonlijke goden. Dat is een verschijnsel dat religiewetenschappers al lang kenden, maar nu is het ook nog eens bevestigd door… een computermodel.

door Maarten Muns

‘JHWH’, de god van het Jodendom, is een van de oudste en strengste goden ter wereld.

wikimedia commons

In de loop van de geschiedenis hebben mensen uiteenlopende soorten goden vereerd. Als je dat van een flinke afstand bekijkt zijn die goden in twee categorieŽn in te delen. Aan de ene kant staan afstandelijke goden, die de wereld geschapen hebben maar zich er verder niet meer mee bemoeien. Ze oordelen niet en houden zich nauwelijks met het leven van mensen bezig. Natuurgoden uit Afrika bijvoorbeeld.

Aan de andere kant bestaan goden die de wereld geschapen hebben en zich er regelmatig tegenaan bemoeien. Deze andere soort zijn strenge, persoonlijke goden. Mensen zijn aan hen verantwoording schuldig en met mensen die zich niet aan bepaalde regels houden kan het wel eens verkeerd aflopen. Een voorbeeld is de god van het Jodendom of bepaalde godsopvattingen binnen het christendom. Binnen deze twee extremen bestaan uiteraard heel veel tussenvormen.

Waar komen al die verschillende soorten goden vandaan? Waarom vereert de ene cultuur een strenge, persoonlijke god vereert en ziet de andere meer in een afstandelijke natuurgod? Dat is een discussie waar religiewetenschappers zich mee bezig houden. Dat strenge, persoonlijke goden vaker opduiken in samenlevingen die een hogere mate van politieke hiŽrarchie en sociale complexiteit hebben is al langer bekend. Een complexe samenleving heeft immers regels nodig, en het geloof in een strenge god die toeziet op die regels is een goed bindmiddel voor zo’n samenleving.

Onvriendelijke omgeving

Maar hoe zit het met ecologische factoren? Een ruiger klimaat leidt immers sneller tot complexe organisatie. Zou er dan ook een verband zijn tussen klimaat en godsbeleving? Het ligt voor de hand, maar is moeilijk aan te tonen. Om dat toch uit te zoeken maakten Amerikaanse evolutionair biologen een computerprogramma. Daarmee brachten ze de factoren in kaart die invloed hebben op de keuze voor een strenge dan wel afstandelijke god. De resultaten beschreven ze in wetenschappelijk tijdschrift PNAS.

In de uitkomst van het computermodel zijn de blauwe stipjes samenlevingen die een strenge, wetgevende god kennen. De rode stipjes kennen die niet. Op de onderliggende kaart zijn ecologische gegevens verwerkt. Wetgevende goden kwamen meer voor op plaatsen waar van nature minder ecologische variatie voorkomt (hoe grijzer het gebied, hoe meer ecologische variatie).

PNAS

De Amerikanen onderzochten de godsbeleving van groot aantal (historische) samenlevingen wereldwijd en vergeleken dat met gegevens over zaken als klimaat, temeratuurvariaties, aanwezigheid van wilde dieren en de beschikbaarheid van voedsel. Er bleek, zoals verwacht, inderdaad een sterk verband te zijn tussen de aanwezigheid van een strenge godheid en politieke complexiteit. Ook was volgens het computermodel de kans op een strenge god groter in samenlevingen die minder toegang tot water en voedsel hebben en in samenlevingen die in een veranderlijk en ruig klimaat leefden. De invloed van verschillende factoren werd zo duidelijk. Er lijkt een duidelijk verband uit het model te komen: In een ruig klimaat ontstaan strenge goden. Het model kon het soort god dat ergens zou ontstaan met 91% zekerheid voorspellen.

Een gedeeld geloof in een persoonlijke god kan helpen angst weg te nemen en zodoende een samenleving beter in staat stellen te overleven in een gevaarlijke en onvriendelijke omgeving. Het is voor het eerst dat een verband tussen ecologie en religie op deze manier aangetoond is. Laten complexe historische en culturele ontwikkelingen zich echt op deze manier verklaren? Niet volledig, want elke situatie is uniek en moet afzonderlijk onderzocht worden om per geval iets zinnigs te kunnen zeggen. Maar computermodellen kunnen geesteswetenschappers wel helpen met overzicht krijgen in moeilijke culturele en historische vraagstukken.

(Kennislink)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

02-12-2014

Inzicht in Jezus en andere obscure joodse sektes

Het boek ‘IsraŽl Verdeeld’ van de eigenzinnige oudheidkundige Jona Lendering is een complexe, maar toch lovenswaardige geschiedenis van de gedeelde oorsprong van twee wereldreligies. Duidelijk wordt in ieder geval dat kerken het geloof in Jezus verkondigen, en zeker niet het geloof van Jezus.

door Maarten Muns

Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep

Ondanks dat de kerk ons graag anders doet geloven, is het beslissende moment in de ontstaansgeschiedenis van het christendom niet de geboorte van Jezus. Ook niet zijn kruisiging of wederopstanding. Het beslissende historische moment was het jaar 70 na het begin van onze jaartelling, toen Romeinse legers na een langdurige en bloedige oorlog de joodse tempel in Jeruzalem vernietigden.

Op dat moment kwam het oude tempel-jodendom ten einde. Het rabbijnse jodendom ontstond, zoals we dat anno nu kennen. De vernietiging van de tempel was ook de aanleiding voor de veelal joodse volgelingen van Jezus van Nazareth om zich als aparte religie te organiseren. Na dat noodlottige jaar 70 n. Chr. groeiden het jonge christendom en het nieuwe rabbijnse jodendom spoedig uit elkaar.

Maar de religies hebben een gedeeld verleden. En het is precies dit gezamenlijke verleden waar oudheidkundige Jona Lendering zich op richt in zijn boek IsraŽl Verdeeld. Hij bespreekt de periode van grofweg 180 v. Chr. tot 70 n. Chr., toen er een heel ander jodendom bestond dan nu. Het offeren van dieren in de tempel stond daarin nog centraal. Er was nog geen vaststaande verzameling religieuze teksten, en geen religieuze autoriteit. Dientengevolge waren allerlei stromingen en sektes met elkaar in discussie over ‘halachische vraagstukken’: hoe te leven volgens de wetten van God? Lendering bespreekt een belangrijke, maar nevelige periode, die veel mťťr is dan een voorbode van Jezus en het christendom.

‘Kwakhistorici’ vs goede historici

Jona Lendering is erop gebrand de methode uit te leggen die oudheidkundigen gebruiken. Dit onderscheidt echte oudhistorici volgens hem van ‘kwakhistorici’, en weerlegt de bergen onzin over de oudheid die vooral op internet te vinden is. De materie is complex en omdat Lendering weigert zaken sensationeler te maken dan ze in werkelijkheid zijn, is zijn boek niet altijd even toegankelijk. Lendering is daar open over. “Als u een page turner zoekt, is dit niet uw boek”, waarschuwt hij vooraf.

Het vergt inderdaad wat inspanning om IsraŽl Verdeeld te lezen. De eerste hoofdstukken, die vooral over de politieke ontwikkelingen gaan, zijn – om eerlijk te zijn – gortdroog. Maar wel van belang: sinds de MakkabeeŽn het koninkrijk Judea aan het Seleucidische Rijk ontworstelden raakten het land en de religie langzaam verdeeld. Het ambt van hogepriester raakte gecorrumpeerd. Op het moment dat de Romeinen het land in 67 v. Chr. annexeerden was elke politieke eenheid ver te zoeken. Bij veel joden leefde de hoop op een messias die eenheid zou brengen, bij anderen het geloof in de eindtijd: God zou de wereld spoedig ten onder doen gaan.

Veel van wat we weten over het voor-Christelijke jodendom komt uit de Dode Zee-rollen, die in 1947 gevonden werden in Qumran, bij de Dode Zee in IsraŽl.

Interessanter wordt het boek wanneer Lendering de religieuze diversiteit in die periode blootlegt en we mogen lezen over obscure sektes als farizeeŽn, essenen, sadducenen en een nationalistisch-achtige ‘vierde filosofie’. Ze worden beschreven door de Romeinse historicus Flavius Josephus (een van de favoriete bronnen van Lendering) die ze vergelijkt met Griekse filosofische stromingen. Een misleidende vergelijking volgens Lendering, maar wat deze sektes wel precies behelsden blijft schimmig.

Oudheidkundigen weten het gewoon niet precies. De fragmentarische bronnen, zoals de beroemde Dode Zee-rollen geven hier en daar een klein inkijkje, maar veel blijft onduidelijk en speculatief. Het is nauwelijks een kritiek te noemen; IsraŽl Verdeeld is niet een boek dat vertelt ‘hoe het zit’, maar eerder een boek dat beschrijft hoe oudheidkundigen op basis van kleine stukjes bewijs een verloren wereld proberen te reconstrueren.

‘De Weg’

Dan de hamvraag: hoe moeten we Jezus van Nazareth plaatsen in deze op alle mogelijke manieren verdeelde, joodse wereld? Hij was een gelover en aankondiger van de eindtijd, zoveel is zeker. Verder was Jezus ‘halfgeschoold en afkomstig uit een provinciestadje, en vertegenwoordigde hij een ander type autoriteit dan de Schriftgeleerden. Hij stond dichter bij de chakram, bij mannen als Honi de Cirkeltrekker, diens zonen en Hanina ben Dosa: mensen die een zo persoonlijke band met God hadden dat ze konden gelden als zijn zonen.’

Het teruggrijpen op vele eerder aangehaalde figuren is kenmerkend voor Lenderings nogal academische stijl (en Honi de Cirkeltrekker is een naam die je dan best weer even in de appendix mag opzoeken) Jezus verkondigde de eindtijd, de ondergang van de huidige orde en de komst van een nieuw koninkrijk, dat van God, waarin ook plaats was voor niet-joden. Een visie die recht tegen elke gevestigde autoriteit inging. Maar hij was tegelijk ook een jood, die zich bezig hield met ‘halacha’: hoe te leven volgens de joodse wet. Lendering probeert het allemaal zo goed mogelijk uit te leggen, hoe moeilijk het allemaal met onze moderne, westerse blik soms te begrijpen is.

De Vernietiging van de tempel in Jeruzalem, schilderij van Francesco Hayez, ItaliŽ, 1867.

Jodenbelasting

Duidelijk is in ieder geval volgens Lendering dat de kerken het geloof in Jezus zijn gaan prediken, en zeker niet het geloof van Jezus. In de verwoesting van de tempel in 70 na Chr. zagen veel van Jezus’ joodse volgelingen een vervulling van zijn profetie, namelijk de ondergang van de wereld. Voor de volgelingen van Jezus waren de machtsaanspraken van het nieuwe Rabbijnse jodendom onaanvaardbaar. Synagogen begonnen de Jezusbeweging uit te sluiten. De Romeinen voerden na de tempelvernietiging voor straf een extra jodenbelasting in (Fiscus Iudaicus) die alle joden moesten afdragen maar waarvan aanhangers van ‘De Weg’ (de Jezusbeweging) vrijgesteld waren. Paulus het geloof in Jezus en de verlossing die het zou brengen open voor niet-joden.

Ergens in de derde of vierde eeuw was de breuk totaal, maar de aandacht die Lendering aan de gebeurtenissen van na 70 besteedt is helaas wat summier. Hoewel IsraŽl Verdeeld erg gedetailleerd is, blijf je als lezer met een hoop vraagtekens achter. Lendering vertelt hoe rijk en divers het voor-christelijke jodendom is, maar geeft tegelijk aan dat oudheidkunde vaak alles behalve sensationeel is. Maar voor mensen die enigszins geÔnteresseerd zijn in het onderwerp is het boek – ondanks Lenderings waarschuwing vooraf – wel degelijk een page turner, omdat het eindelijk inzicht geeft in wat we wel en vooral ook wat we allemaal niet weten.

Deze recensie verscheen eerder op de website van Athenaeum

(Kennislink.nl)

Inzicht in Jezus en andere obscure joodse sektes

Het boek ‘IsraŽl Verdeeld’ van de eigenzinnige oudheidkundige Jona Lendering is een complexe, maar toch lovenswaardige geschiedenis van de gedeelde oorsprong van twee wereldreligies. Duidelijk wordt in ieder geval dat kerken het geloof in Jezus verkondigen, en zeker niet het geloof van Jezus.

door Maarten Muns

Athenaeum-Polak & Van Gennep

Ondanks dat de kerk ons graag anders doet geloven, is het beslissende moment in de ontstaansgeschiedenis van het christendom niet de geboorte van Jezus. Ook niet zijn kruisiging of wederopstanding. Het beslissende historische moment was het jaar 70 na het begin van onze jaartelling, toen Romeinse legers na een langdurige en bloedige oorlog de joodse tempel in Jeruzalem vernietigden.

Op dat moment kwam het oude tempel-jodendom ten einde. Het rabbijnse jodendom ontstond, zoals we dat anno nu kennen. De vernietiging van de tempel was ook de aanleiding voor de veelal joodse volgelingen van Jezus van Nazareth om zich als aparte religie te organiseren. Na dat noodlottige jaar 70 n. Chr. groeiden het jonge christendom en het nieuwe rabbijnse jodendom spoedig uit elkaar.

Maar de religies hebben een gedeeld verleden. En het is precies dit gezamenlijke verleden waar oudheidkundige Jona Lendering zich op richt in zijn boek IsraŽl Verdeeld. Hij bespreekt de periode van grofweg 180 v. Chr. tot 70 n. Chr., toen er een heel ander jodendom bestond dan nu. Het offeren van dieren in de tempel stond daarin nog centraal. Er was nog geen vaststaande verzameling religieuze teksten, en geen religieuze autoriteit. Dientengevolge waren allerlei stromingen en sektes met elkaar in discussie over ‘halachische vraagstukken’: hoe te leven volgens de wetten van God? Lendering bespreekt een belangrijke, maar nevelige periode, die veel mťťr is dan een voorbode van Jezus en het christendom.

‘Kwakhistorici’ vs goede historici

Jona Lendering is erop gebrand de methode uit te leggen die oudheidkundigen gebruiken. Dit onderscheidt echte oudhistorici volgens hem van ‘kwakhistorici’, en weerlegt de bergen onzin over de oudheid die vooral op internet te vinden is. De materie is complex en omdat Lendering weigert zaken sensationeler te maken dan ze in werkelijkheid zijn, is zijn boek niet altijd even toegankelijk. Lendering is daar open over. “Als u een page turner zoekt, is dit niet uw boek”, waarschuwt hij vooraf.

Het vergt inderdaad wat inspanning om IsraŽl Verdeeld te lezen. De eerste hoofdstukken, die vooral over de politieke ontwikkelingen gaan, zijn – om eerlijk te zijn – gortdroog. Maar wel van belang: sinds de MakkabeeŽn het koninkrijk Judea aan het Seleucidische Rijk ontworstelden raakten het land en de religie langzaam verdeeld. Het ambt van hogepriester raakte gecorrumpeerd. Op het moment dat de Romeinen het land in 67 v. Chr. annexeerden was elke politieke eenheid ver te zoeken. Bij veel joden leefde de hoop op een messias die eenheid zou brengen, bij anderen het geloof in de eindtijd: God zou de wereld spoedig ten onder doen gaan.

Veel van wat we weten over het voor-Christelijke jodendom komt uit de Dode Zee-rollen, die in 1947 gevonden werden in Qumran, bij de Dode Zee in IsraŽl.

Interessanter wordt het boek wanneer Lendering de religieuze diversiteit in die periode blootlegt en we mogen lezen over obscure sektes als farizeeŽn, essenen, sadducenen en een nationalistisch-achtige ‘vierde filosofie’. Ze worden beschreven door de Romeinse historicus Flavius Josephus (een van de favoriete bronnen van Lendering) die ze vergelijkt met Griekse filosofische stromingen. Een misleidende vergelijking volgens Lendering, maar wat deze sektes wel precies behelsden blijft schimmig.

Oudheidkundigen weten het gewoon niet precies. De fragmentarische bronnen, zoals de beroemde Dode Zee-rollen geven hier en daar een klein inkijkje, maar veel blijft onduidelijk en speculatief. Het is nauwelijks een kritiek te noemen; IsraŽl Verdeeld is niet een boek dat vertelt ‘hoe het zit’, maar eerder een boek dat beschrijft hoe oudheidkundigen op basis van kleine stukjes bewijs een verloren wereld proberen te reconstrueren.

‘De Weg’

Dan de hamvraag: hoe moeten we Jezus van Nazareth plaatsen in deze op alle mogelijke manieren verdeelde, joodse wereld? Hij was een gelover en aankondiger van de eindtijd, zoveel is zeker. Verder was Jezus ‘halfgeschoold en afkomstig uit een provinciestadje, en vertegenwoordigde hij een ander type autoriteit dan de Schriftgeleerden. Hij stond dichter bij de chakram, bij mannen als Honi de Cirkeltrekker, diens zonen en Hanina ben Dosa: mensen die een zo persoonlijke band met God hadden dat ze konden gelden als zijn zonen.’

Het teruggrijpen op vele eerder aangehaalde figuren is kenmerkend voor Lenderings nogal academische stijl (en Honi de Cirkeltrekker is een naam die je dan best weer even in de appendix mag opzoeken) Jezus verkondigde de eindtijd, de ondergang van de huidige orde en de komst van een nieuw koninkrijk, dat van God, waarin ook plaats was voor niet-joden. Een visie die recht tegen elke gevestigde autoriteit inging. Maar hij was tegelijk ook een jood, die zich bezig hield met ‘halacha’: hoe te leven volgens de joodse wet. Lendering probeert het allemaal zo goed mogelijk uit te leggen, hoe moeilijk het allemaal met onze moderne, westerse blik soms te begrijpen is.

De Vernietiging van de tempel in Jeruzalem, schilderij van Francesco Hayez, ItaliŽ, 1867.

Jodenbelasting

Duidelijk is in ieder geval volgens Lendering dat de kerken het geloof in Jezus zijn gaan prediken, en zeker niet het geloof van Jezus. In de verwoesting van de tempel in 70 na Chr. zagen veel van Jezus’ joodse volgelingen een vervulling van zijn profetie, namelijk de ondergang van de wereld. Voor de volgelingen van Jezus waren de machtsaanspraken van het nieuwe Rabbijnse jodendom onaanvaardbaar. Synagogen begonnen de Jezusbeweging uit te sluiten. De Romeinen voerden na de tempelvernietiging voor straf een extra jodenbelasting in (Fiscus Iudaicus) die alle joden moesten afdragen maar waarvan aanhangers van ‘De Weg’ (de Jezusbeweging) vrijgesteld waren. Paulus het geloof in Jezus en de verlossing die het zou brengen open voor niet-joden.

Ergens in de derde of vierde eeuw was de breuk totaal, maar de aandacht die Lendering aan de gebeurtenissen van na 70 besteedt is helaas wat summier. Hoewel IsraŽl Verdeeld erg gedetailleerd is, blijf je als lezer met een hoop vraagtekens achter. Lendering vertelt hoe rijk en divers het voor-christelijke jodendom is, maar geeft tegelijk aan dat oudheidkunde vaak alles behalve sensationeel is. Maar voor mensen die enigszins geÔnteresseerd zijn in het onderwerp is het boek – ondanks Lenderings waarschuwing vooraf – wel degelijk een page turner, omdat het eindelijk inzicht geeft in wat we wel en vooral ook wat we allemaal niet weten.

Deze recensie verscheen eerder op de website van Athenaeum

(Kennislink.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

VATICAN OBSERVATORY WHERE PRIESTS ARE ALSO ASTROPHYSICISTS

3 February 2015 Last updated at 03:41 GMT

The desert landscape in America's South West is literally awe-inspiring - the scale, the beauty and the sheer emptiness has always made humans question their place in the Universe.

That is particularly true at night when the sky, unpolluted by man-made light sources, is filled with stars.

It is no surprise, then, that the mountains in Arizona are home to many observatories where scientists from all over the world come to study the cosmos. What is less well known, is that the Vatican has long had its own observatory here too.

BBC Pop Up's Matt Danzico met two of the Jesuit priests who are also astrophysicists to find out more about this unexpected convergence of religion and science.

You can find out all about the aims of the Pop Up project and see all the videos from the first four months. Check out Pop Up's behind-the-scenes blog to see how to get involved.

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-31051635

3 February 2015 Last updated at 03:41 GMT

The desert landscape in America's South West is literally awe-inspiring - the scale, the beauty and the sheer emptiness has always made humans question their place in the Universe.

That is particularly true at night when the sky, unpolluted by man-made light sources, is filled with stars.

It is no surprise, then, that the mountains in Arizona are home to many observatories where scientists from all over the world come to study the cosmos. What is less well known, is that the Vatican has long had its own observatory here too.

BBC Pop Up's Matt Danzico met two of the Jesuit priests who are also astrophysicists to find out more about this unexpected convergence of religion and science.

You can find out all about the aims of the Pop Up project and see all the videos from the first four months. Check out Pop Up's behind-the-scenes blog to see how to get involved.

http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-31051635

“The fundamental cause of the trouble in the modern world today is that the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.”— Bertrand Russell

08-04-2015

"Jezus lag met vrouw en zoon begraven in Jeruzalem"

Na ruim 150 chemische tests weet geoloog Arye Shimron het bijna zeker: Jezus van Nazareth is na Pasen niet opgestaan uit zijn graf en later ten hemel gevaren. Nee, Jezus lag begraven in het graf van Talpiot in het zuidoosten van Jeruzalem. Bovendien lag hij daar niet alleen. Hij was getrouwd met Maria en had een zoon, Judas. Ook zij lagen in het graf.

Dr. Arye Shimron © Screenshot NBC News.

Een fragment uit de documentaire Het Verloren Graf van Jezus © Screenshot YouTube.

De beweringen van de IsraŽlische geoloog werden deze week opgetekend in 'The New York Times' en 'The Jerusalem Post'. Ze vormen een nieuwe episode in een discussie die al zo'n 35 jaar duurt.

Jezus, zoon van Jozef

Al in 1980 werd in Talpiot een familiegraf gevonden, met daarin tien ossuaria. In de kalkstenen grafkisten zaten de overblijfselen van tien personen, hun namen waren in het Aramees in het kalk gekrast. Het gaat om 'Jezus, zoon van Jozef', 'Mariamme e mara' (zijn vrouw Maria), en 'Judas, zoon van Jezus'. Ook lagen er een Maria (zijn moeder), MattheŁs, Jozef (een broer), en Yose (een naam die in het Nieuwe Testament wordt gelinkt aan een andere broer van Jezus).

Dat in die tijd oude graven werden gevonden, was niet vreemd. In Jeruzalem werd in die jaren veel gebouwd. Honderden graven uit de tijd van Jezus kwamen aan de oppervlakte tijdens de vele graafwerkzaamheden. Ook het feit dat in het graf de namen werden gevonden van Bijbelse figuren hoefde niet te verbazen.

"Normale namen"

Statistici van de universiteit van Toronto berekenden dat in de tijd van Jezus en zijn aanhang ongeveer 8 procent van de mensen in die streek zo'n naam had. "Jezus was een normale naam in die tijd, net zoals Hans en Peter dat nu zijn. En Maria was dat ook", zegt Lucas Petit, een Nederlandse conservator van het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden.

Maar dat al die namen op deze manier werden teruggevonden binnen ťťn familie, was volgens Shimron wel opvallend. Hij kreeg daarbij steun van Simcha Jacobovici, een Canadese documentairemaker met IsraŽlische roots. Mogelijk ging het hier om het familiegraf van Jezus van Nazareth?

Het Verloren Graf

In 2007 toonde Jacobovici zijn documentaire 'Het Verloren Graf van Jezus' op Discovery Channel. Daarin werd ook gemeld dat Jezus was getrouwd met Maria Magdalena.

Critici meldden dat Shimron en zijn metgezel te snel conclusies trokken. Dat zouden ze vooral doen om reclame te maken voor de film. Ook Petit denkt er overigens zo over. "Ze hebben dat toen slim aangepakt in de aanloop naar die film." Ook het verhaal in de documentaire is volgens hem gekunsteld. "Er worden bepaalde zaken uitgelicht en andere bewust weggelaten."

Bekijk de trailer hieronder.

http://static1.hln.be/sta(...)/media_l_7620017.jpg

Het gesteente van de ossuaria uit het familiegraf werden onderzocht in een laboratorium © Screenshot NBC News.

Een van de ossuaria uit het mogelijke familiegraf van Jezus van Nazareth © Screenshot NBC News.

Jacobus, broer van Jezus

Tegenstanders wezen ook op het kalkstenen ossuarium met de inscriptie 'Jacobus, zoon van Jozef, broer van Jezus'. Deze dook in 2002 op bij Oded Golan, een antiekverzamelaar die zei het ding in de jaren zeventig gekocht te hebben.

Hoewel men erachter kwam dat ťťn van de tien kistjes uit het graf van Talpiot was verdwenen uit het magazijn waarin zij werden bewaard, werd Golan door de Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA) beschuldigd van fraude: de inscriptie zou vals zijn. Golan werd in 2012 uiteindelijk vrijgesproken door een rechtbank in Jeruzalem. Zijn vrijspraak betekende volgens de autoriteiten echter niet dat het kistje van Jacobus echt was.

Analyse en tests

Ongeveer twee weken geleden kreeg Shimron toegang tot de kalkstenen grafkist van 'Jacobus'. De geoloog schraapte stukjes kalksteen en resten grond van het ding en vergeleek dat met stukjes steen en resten grond van de andere negen kisten uit het graf. Hij deed hetzelfde met vijftien andere willekeurige grafkisten.

In 150 ŗ 200 tests vond Shimron resten magnesium en ijzer die erop wezen dat het kistje van Jacobus in precies dezelfde omstandigheden was bewaard als dat van zijn negen familieleden. Deze Jacobus was een broer van Jezus, die weer een zoon van Jozef en Maria was. "Het bewijs kon niet sterker zijn", aldus Shimron tegen NBC News. "Wie in Liverpool een graf zou vinden met de namen van de vier Beatles erop zou ook zeker weten dat dat het graf van de vier Beatles zou zijn en niet van een andere band."

"Volgens mij heeft hij een gigantische ontdekking gedaan", zegt Jacobovici over de vondsten van Shimron. "Ik volg hem al ruim zeven jaar. Dit is geen ondoordacht onderzoek geweest."

"Haast onmogelijk"

Als de beweringen van Shimron waar blijken te zijn, dan zou dat het bijbelverhaal fors schaden. Christenen gaan immers uit van de verrijzenis van Jezus. Bovendien wordt in de Bijbel niet gerept over een vrouw en een zoon.

Petit, die twee maanden per jaar aan opgravingen werkt in de Jordaanvallei, nuanceert de bevindingen van Shimron echter stevig. "Het is een interessant graf, met die namen op die locatie en uit de tijd van Jezus. En het is ook goed dat erover gediscussieerd wordt. Maar we moeten deze vondsten los zien van de religieuze figuur Jezus. Ontdekkingen als deze vertellen ons meer over gezinssamenstellingen en over hoe mensen samenleefden. Het is haast onmogelijk om figuren die tweeduizend jaar geleden leefden te verbinden aan een vondst als deze. De archeologie is er niet om het bestaan van Jezus te bewijzen."

(HLN)

"Jezus lag met vrouw en zoon begraven in Jeruzalem"

Na ruim 150 chemische tests weet geoloog Arye Shimron het bijna zeker: Jezus van Nazareth is na Pasen niet opgestaan uit zijn graf en later ten hemel gevaren. Nee, Jezus lag begraven in het graf van Talpiot in het zuidoosten van Jeruzalem. Bovendien lag hij daar niet alleen. Hij was getrouwd met Maria en had een zoon, Judas. Ook zij lagen in het graf.

Dr. Arye Shimron © Screenshot NBC News.

Een fragment uit de documentaire Het Verloren Graf van Jezus © Screenshot YouTube.

De beweringen van de IsraŽlische geoloog werden deze week opgetekend in 'The New York Times' en 'The Jerusalem Post'. Ze vormen een nieuwe episode in een discussie die al zo'n 35 jaar duurt.

Jezus, zoon van Jozef

Al in 1980 werd in Talpiot een familiegraf gevonden, met daarin tien ossuaria. In de kalkstenen grafkisten zaten de overblijfselen van tien personen, hun namen waren in het Aramees in het kalk gekrast. Het gaat om 'Jezus, zoon van Jozef', 'Mariamme e mara' (zijn vrouw Maria), en 'Judas, zoon van Jezus'. Ook lagen er een Maria (zijn moeder), MattheŁs, Jozef (een broer), en Yose (een naam die in het Nieuwe Testament wordt gelinkt aan een andere broer van Jezus).

Dat in die tijd oude graven werden gevonden, was niet vreemd. In Jeruzalem werd in die jaren veel gebouwd. Honderden graven uit de tijd van Jezus kwamen aan de oppervlakte tijdens de vele graafwerkzaamheden. Ook het feit dat in het graf de namen werden gevonden van Bijbelse figuren hoefde niet te verbazen.

"Normale namen"

Statistici van de universiteit van Toronto berekenden dat in de tijd van Jezus en zijn aanhang ongeveer 8 procent van de mensen in die streek zo'n naam had. "Jezus was een normale naam in die tijd, net zoals Hans en Peter dat nu zijn. En Maria was dat ook", zegt Lucas Petit, een Nederlandse conservator van het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in Leiden.

Maar dat al die namen op deze manier werden teruggevonden binnen ťťn familie, was volgens Shimron wel opvallend. Hij kreeg daarbij steun van Simcha Jacobovici, een Canadese documentairemaker met IsraŽlische roots. Mogelijk ging het hier om het familiegraf van Jezus van Nazareth?

Het Verloren Graf

In 2007 toonde Jacobovici zijn documentaire 'Het Verloren Graf van Jezus' op Discovery Channel. Daarin werd ook gemeld dat Jezus was getrouwd met Maria Magdalena.

Critici meldden dat Shimron en zijn metgezel te snel conclusies trokken. Dat zouden ze vooral doen om reclame te maken voor de film. Ook Petit denkt er overigens zo over. "Ze hebben dat toen slim aangepakt in de aanloop naar die film." Ook het verhaal in de documentaire is volgens hem gekunsteld. "Er worden bepaalde zaken uitgelicht en andere bewust weggelaten."

Bekijk de trailer hieronder.

http://static1.hln.be/sta(...)/media_l_7620017.jpg

Het gesteente van de ossuaria uit het familiegraf werden onderzocht in een laboratorium © Screenshot NBC News.

Een van de ossuaria uit het mogelijke familiegraf van Jezus van Nazareth © Screenshot NBC News.

Jacobus, broer van Jezus

Tegenstanders wezen ook op het kalkstenen ossuarium met de inscriptie 'Jacobus, zoon van Jozef, broer van Jezus'. Deze dook in 2002 op bij Oded Golan, een antiekverzamelaar die zei het ding in de jaren zeventig gekocht te hebben.

Hoewel men erachter kwam dat ťťn van de tien kistjes uit het graf van Talpiot was verdwenen uit het magazijn waarin zij werden bewaard, werd Golan door de Israeli Antiquities Authority (IAA) beschuldigd van fraude: de inscriptie zou vals zijn. Golan werd in 2012 uiteindelijk vrijgesproken door een rechtbank in Jeruzalem. Zijn vrijspraak betekende volgens de autoriteiten echter niet dat het kistje van Jacobus echt was.

Analyse en tests

Ongeveer twee weken geleden kreeg Shimron toegang tot de kalkstenen grafkist van 'Jacobus'. De geoloog schraapte stukjes kalksteen en resten grond van het ding en vergeleek dat met stukjes steen en resten grond van de andere negen kisten uit het graf. Hij deed hetzelfde met vijftien andere willekeurige grafkisten.

In 150 ŗ 200 tests vond Shimron resten magnesium en ijzer die erop wezen dat het kistje van Jacobus in precies dezelfde omstandigheden was bewaard als dat van zijn negen familieleden. Deze Jacobus was een broer van Jezus, die weer een zoon van Jozef en Maria was. "Het bewijs kon niet sterker zijn", aldus Shimron tegen NBC News. "Wie in Liverpool een graf zou vinden met de namen van de vier Beatles erop zou ook zeker weten dat dat het graf van de vier Beatles zou zijn en niet van een andere band."

"Volgens mij heeft hij een gigantische ontdekking gedaan", zegt Jacobovici over de vondsten van Shimron. "Ik volg hem al ruim zeven jaar. Dit is geen ondoordacht onderzoek geweest."

"Haast onmogelijk"

Als de beweringen van Shimron waar blijken te zijn, dan zou dat het bijbelverhaal fors schaden. Christenen gaan immers uit van de verrijzenis van Jezus. Bovendien wordt in de Bijbel niet gerept over een vrouw en een zoon.

Petit, die twee maanden per jaar aan opgravingen werkt in de Jordaanvallei, nuanceert de bevindingen van Shimron echter stevig. "Het is een interessant graf, met die namen op die locatie en uit de tijd van Jezus. En het is ook goed dat erover gediscussieerd wordt. Maar we moeten deze vondsten los zien van de religieuze figuur Jezus. Ontdekkingen als deze vertellen ons meer over gezinssamenstellingen en over hoe mensen samenleefden. Het is haast onmogelijk om figuren die tweeduizend jaar geleden leefden te verbinden aan een vondst als deze. De archeologie is er niet om het bestaan van Jezus te bewijzen."

(HLN)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

23-07-2015

1.500 jaar oude Koran stamt uit de tijd van profeet Mohammed

Geschreven door Tim Kraaijvanger op 23 juli 2015 om 08:29 uur

Wetenschappers van de universiteit van Birmingham hebben een stokoud exemplaar van de Koran gedateerd. Het heilige boek is circa 1.500 jaar oud.

De onderzoekers gebruikten C14-datering om de leeftijd van de organische materialen – die gebruikt zijn om het boek te maken – te bepalen. De tekst in deze Koran is met 95,4% zekerheid geschreven tussen het jaar 568 en 645 na Christus. Dit is in dezelfde periode dat profeet Mohammed leefde. Mohammed werd rond het jaar 570 na Christus geboren en stierf in 632.

Koolstofdatering is een betrouwbare manier om de leeftijd van een materiaal te bepalen. Het perkament dat gebruikt is voor de oudste Koran is gemaakt van de huid van een kalf, geit of schaap.

Algemeen wordt aangenomen dat Mohammed analfabeet was en niet kon schrijven of lezen. Toen de profeet in Mohammed stierf, bestond er nog geen complete, schriftelijke korantekst. De volgers van Mohammed onthielden de openbaringen van hun profeet. Pas enkele decennia na het overlijden van Mohammed werden de teksten opgeschreven. De oudste Koran is niet later dan twee decennia na de dood van Mohammed geschreven en bevat de soera’s (hoofdstukken) 18 tot 20. De tekst is geschreven in het Hidjazi-Arabisch. Dit is een taal die vandaag de dag nog steeds wordt gesproken door veel inwoners in het westen van Saoedie-ArabiŽ.

Benieuwd naar de oudste Koran? Dit boek is van vrijdag 2 oktober tot zondag 25 oktober te zien in The Barber Institute of Fine Arts van de universiteit van Birmingham.

(scientias.nl)

1.500 jaar oude Koran stamt uit de tijd van profeet Mohammed

Geschreven door Tim Kraaijvanger op 23 juli 2015 om 08:29 uur

Wetenschappers van de universiteit van Birmingham hebben een stokoud exemplaar van de Koran gedateerd. Het heilige boek is circa 1.500 jaar oud.

De onderzoekers gebruikten C14-datering om de leeftijd van de organische materialen – die gebruikt zijn om het boek te maken – te bepalen. De tekst in deze Koran is met 95,4% zekerheid geschreven tussen het jaar 568 en 645 na Christus. Dit is in dezelfde periode dat profeet Mohammed leefde. Mohammed werd rond het jaar 570 na Christus geboren en stierf in 632.

Koolstofdatering is een betrouwbare manier om de leeftijd van een materiaal te bepalen. Het perkament dat gebruikt is voor de oudste Koran is gemaakt van de huid van een kalf, geit of schaap.

Algemeen wordt aangenomen dat Mohammed analfabeet was en niet kon schrijven of lezen. Toen de profeet in Mohammed stierf, bestond er nog geen complete, schriftelijke korantekst. De volgers van Mohammed onthielden de openbaringen van hun profeet. Pas enkele decennia na het overlijden van Mohammed werden de teksten opgeschreven. De oudste Koran is niet later dan twee decennia na de dood van Mohammed geschreven en bevat de soera’s (hoofdstukken) 18 tot 20. De tekst is geschreven in het Hidjazi-Arabisch. Dit is een taal die vandaag de dag nog steeds wordt gesproken door veel inwoners in het westen van Saoedie-ArabiŽ.

Benieuwd naar de oudste Koran? Dit boek is van vrijdag 2 oktober tot zondag 25 oktober te zien in The Barber Institute of Fine Arts van de universiteit van Birmingham.

(scientias.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

12-04-2016

Bijbel lijkt ouder te zijn dan gedacht

Nieuw onderzoek suggereert dat een deel van de Hebreeuwse Bijbel al voor de val van het koninkrijk van Juda werd samengesteld.

In 586 voor Christus werd Jeruzalem verwoest en kwam er – door toedoen van de Perzen – een einde aan het koninkrijk van Juda. Wetenschappers breken zich al lang het hoofd over de vraag of de Hebreeuwse Bijbel (het oude testament) voordat de Perzen in 586 verwoesting brachten al grotendeels was samengesteld of dat dat pas daarna gebeurde. Een nieuw onderzoek kan wellicht meer duidelijkheid scheppen.

Compilatie

De meeste wetenschappers zijn het er wel over eens dat belangrijke teksten uit de Hebreeuwse Bijbel vanaf de zevende eeuw voor Christus werden opgeschreven. Maar wanneer werden die teksten samengevoegd om het verzamelwerk te vormen dat de Hebreeuwse Bijbel nu is? Dat bleef onduidelijk. Wetenschappers vroegen zich met name af of de verschillende teksten vůůr of na 586 voor Christus werden samengevoegd. 586 voor Christus is een belangrijk moment in de geschiedenis van het Joodse volk: in dat jaar verwoestten de Perzen Jeruzalem, kwam er een einde aan het koninkrijk van Juda en werd de Joods elite in ballingschap naar BabyloniŽ gevoerd.

.

Inwoners van het gevallen koninkrijk van Juda worden weggevoerd naar BabyloniŽ. Afbeelding: via Wikimedia Commons.

Geletterdheid

“Er is een verhitte discussie gaande omtrent het moment waarop een groot aantal bijbelse teksten werd samengevoegd,” stelt onderzoeker Israel Finkelstein. “Maar om dit helder te krijgen, moet je een bredere vraag stellen: hoe zat het met de geletterdheid in Juda (kort voor de Perzen het koninkrijk van de kaart veegden, red.)? En hoe zat het met de geletterdheid onder de macht van de Perzen?” Finkelstein en zijn collega’s stellen namelijk dat het samenvoegen van bijbelse teksten een enorme klus was, waar veel geletterde mensen bij betrokken moeten zijn geweest. De compilatie kan dan ook alleen maar ontstaan zijn in een tijd waarin veel individuen konden lezen en schrijven. Grote vraag is of dat in de laatste dagen van het koninkrijk van Juda al het geval was.

Teksten in een fort

Om een antwoord te krijgen op die vraag bestudeerden wetenschappers zestien teksten die tijdens een opgraving in een afgelegen fort waren teruggevonden. De teksten stammen uit 600 voor Christus en gaan over de bewegingen van militaire troepen, maar ook over de kosten van voedsel. Een analyse toont aan dat de teksten het werk zijn van zeker zes verschillende schrijvers. Dat zich onder de weinige soldaten in dit afgelegen fort al zoveel geletterde individuen bevonden, suggereert dat het met de geletterdheid in de laatste dagen van Juda wel goed zat. “We hebben indirect bewijs gevonden voor een educatieve infrastructuur die de compositie van bijbelse teksten mogelijk moet hebben gemaakt,” stelt onderzoeker Eliezer Piasetzky. “In alle lagen van de overheid, het leger en de priesters van Juda was sprake van geletterdheid. Lezen en schrijven was niet alleen weggelegd voor de elite.”

.

De teksten die de wetenschappers analyseerden. Afbeelding: Michael Cordonsky / Tel Aviv University / Israel Antiquities Authority.

En daarmee wordt het heel aannemelijk dat de Hebreeuwse bijbel grotendeels al voor de ballingschap werd samengesteld, zo stellen de onderzoekers. “Na de val van Juda werden er tot de tweede eeuw voor Christus weinig Hebreeuwse teksten geproduceerd,” stelt Finkelstein. “Dat verkleint de kans dat er tussen 586 en 200 voor Christus een compilatie van bijbelse literatuur werd gemaakt.”

(scientias.nl)

Bijbel lijkt ouder te zijn dan gedacht

Nieuw onderzoek suggereert dat een deel van de Hebreeuwse Bijbel al voor de val van het koninkrijk van Juda werd samengesteld.

In 586 voor Christus werd Jeruzalem verwoest en kwam er – door toedoen van de Perzen – een einde aan het koninkrijk van Juda. Wetenschappers breken zich al lang het hoofd over de vraag of de Hebreeuwse Bijbel (het oude testament) voordat de Perzen in 586 verwoesting brachten al grotendeels was samengesteld of dat dat pas daarna gebeurde. Een nieuw onderzoek kan wellicht meer duidelijkheid scheppen.

Compilatie

De meeste wetenschappers zijn het er wel over eens dat belangrijke teksten uit de Hebreeuwse Bijbel vanaf de zevende eeuw voor Christus werden opgeschreven. Maar wanneer werden die teksten samengevoegd om het verzamelwerk te vormen dat de Hebreeuwse Bijbel nu is? Dat bleef onduidelijk. Wetenschappers vroegen zich met name af of de verschillende teksten vůůr of na 586 voor Christus werden samengevoegd. 586 voor Christus is een belangrijk moment in de geschiedenis van het Joodse volk: in dat jaar verwoestten de Perzen Jeruzalem, kwam er een einde aan het koninkrijk van Juda en werd de Joods elite in ballingschap naar BabyloniŽ gevoerd.

.

Inwoners van het gevallen koninkrijk van Juda worden weggevoerd naar BabyloniŽ. Afbeelding: via Wikimedia Commons.

Geletterdheid

“Er is een verhitte discussie gaande omtrent het moment waarop een groot aantal bijbelse teksten werd samengevoegd,” stelt onderzoeker Israel Finkelstein. “Maar om dit helder te krijgen, moet je een bredere vraag stellen: hoe zat het met de geletterdheid in Juda (kort voor de Perzen het koninkrijk van de kaart veegden, red.)? En hoe zat het met de geletterdheid onder de macht van de Perzen?” Finkelstein en zijn collega’s stellen namelijk dat het samenvoegen van bijbelse teksten een enorme klus was, waar veel geletterde mensen bij betrokken moeten zijn geweest. De compilatie kan dan ook alleen maar ontstaan zijn in een tijd waarin veel individuen konden lezen en schrijven. Grote vraag is of dat in de laatste dagen van het koninkrijk van Juda al het geval was.

Teksten in een fort

Om een antwoord te krijgen op die vraag bestudeerden wetenschappers zestien teksten die tijdens een opgraving in een afgelegen fort waren teruggevonden. De teksten stammen uit 600 voor Christus en gaan over de bewegingen van militaire troepen, maar ook over de kosten van voedsel. Een analyse toont aan dat de teksten het werk zijn van zeker zes verschillende schrijvers. Dat zich onder de weinige soldaten in dit afgelegen fort al zoveel geletterde individuen bevonden, suggereert dat het met de geletterdheid in de laatste dagen van Juda wel goed zat. “We hebben indirect bewijs gevonden voor een educatieve infrastructuur die de compositie van bijbelse teksten mogelijk moet hebben gemaakt,” stelt onderzoeker Eliezer Piasetzky. “In alle lagen van de overheid, het leger en de priesters van Juda was sprake van geletterdheid. Lezen en schrijven was niet alleen weggelegd voor de elite.”

.

De teksten die de wetenschappers analyseerden. Afbeelding: Michael Cordonsky / Tel Aviv University / Israel Antiquities Authority.

En daarmee wordt het heel aannemelijk dat de Hebreeuwse bijbel grotendeels al voor de ballingschap werd samengesteld, zo stellen de onderzoekers. “Na de val van Juda werden er tot de tweede eeuw voor Christus weinig Hebreeuwse teksten geproduceerd,” stelt Finkelstein. “Dat verkleint de kans dat er tussen 586 en 200 voor Christus een compilatie van bijbelse literatuur werd gemaakt.”

(scientias.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

CONSCIOUSNESS OCCURS IN 'TIME SLICES' LASTING ONLY MILLISECONDS, STUDY SUGGESTS

Think quickly.

The question of how exactly we experience the world through our perception of consciousness is one that's long intrigued scientists and philosophers. And at its core are two divergent hypotheses.

On the one hand, it could be that consciousness exists as a constant, uninterrupted stream of perception, like how it feels to watch a movie. You sit down with your popcorn and experience a film from beginning to end in one continuous flow, unaware of any segmentation or breakup as you go.

But another hypothesis of consciousness reflects what a film technically is: a series of individual frames of time stitched together into a reel that – when played back – appear seamless. So which is it? Is consciousness a seamless film, or is it a reel composed of discrete moments?

According to a new study by Swiss psychophysicists, neither hypothesis is truly correct. Rather, they propose a new two-stage model for how we process information, which they say reconciles the 'continuous vs discrete' debate.

In their model, 'time slices' consisting of unconscious processing of stimuli last for up to 400 milliseconds (ms), and are immediately followed by the conscious perception of events.

"The reason is that the brain wants to give you the best, clearest information it can, and this demands a substantial amount of time," said researcher Michael Herzog from the …cole Polytechnique Fťdťrale de Lausanne (EPFL). "There is no advantage in making you aware of its unconscious processing, because that would be immensely confusing."

According to Herzog and fellow researcher Frank Scharnowski from the University of Zurich, neither the 'continuous' nor 'discrete' hypotheses can by themselves aptly describe how we process the world around us, as numerous studies testing people's visual awareness seem to disprove both notions.

But what if elements of both hypotheses were taking place at the same time in a continuous interplay between conscious and unconscious thought?

"According to our model, the elements of a visual scene are first unconsciously analysed. This period can last up to 400 ms and involves, amongst other processes, the analysis of stimulus features such as the orientation or colour of elements and temporal features such as object duration and object simultaneity," the authors write in PLOS Biology.

After this analysis is complete, the researchers say the features we've detected are integrated into our conscious perception, compressing all the unconscious recording into something we're actually aware of.

In other words, while we're taking the world in, we're not actually consciously perceiving it. Instead, we're just mutely using our senses to record data for up to 400 ms at a time. Then, in what could be called a moment of clarity, we consciously perceive the stimuli that our senses have detected.

The team thinks this presentation of information to our consciousness lasts for about 50 milliseconds, during which we also stop taking new sensory information in. And then repeat.

Our senses start taking new information in from whatever stimuli are around us, before handing it off to our consciousness to perceive and enjoy – back and forth, and so on, and so on.

The team says each window of recording and playback would last for a different amount of time, depending on the kind of information being processed.

While the constant to-and-fro suggests consciousness is anything but a seamless experience, if the researchers are correct, our brains somehow manage to stitch everything together so it feels like a continuous flow of events with no interruptions.

"Metaphorically, such a representation is akin to the answer to the question of how were your holidays: 'We enjoyed the colours of the Tuscan landscape for three days and then went to Venice for four sunny days at the sea'," the authors write. "The response is a compressed post-hoc description regarding the temporal features of the trip, even though the actual event was spread over a long period of time."

The scientists acknowledge that future research is needed to shed light on whether their hypothesised 'time slices' are indeed a more accurate representation of the way we experience reality, but it's a fascinating idea.

http://www.sciencealert.c(...)conds-study-suggests

“The fundamental cause of the trouble in the modern world today is that the stupid are cocksure while the intelligent are full of doubt.”— Bertrand Russell

interessant

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

15-04-2016

‘Wetenschap zal nooit bewustzijn kunnen verklaren’

Hoe ons bewustzijn echt werkt? De wetenschap gaat het ons niet vertellen, betoogt de Duitse sterfilosoof Markus Gabriel. En passant opent hij de aanval op Dick Swaab, ‘de radicaalste van alle gekke neurowetenschappers’.

Markus Gabriel: ‘De neurowetenschap zou een puur medische functie moeten hebben.’ Bron: Flickr/neil conway

Op 29-jarige leeftijd werd Markus Gabriel aangesteld als jongste hoogleraar in de filosofie ooit aan de Universiteit Bonn. Met de reeks boeken die achter zijn naam staat, heeft de inmiddels 35-jarige zich gevestigd als titaan in de filosofie. Hij brak door met Waarom de wereld niet bestaat, waarin hij beargumenteerde dat alles wat wij ons kunnen verbeelden bestaat, zelfs eenhoorns – maar de wereld zelf niet, want daar kunnen wij ons geen voorstelling van maken. In zijn laatste werk Waarom we vrij zijn als we denken heeft Gabriel een nieuw slachtoffer gevonden: de neurowetenschap.

De Duitse titel van uw boek Ich ist nicht Gehirn (Ik is niet het brein) is afgeleid van Dick Swaabs Wij zijn ons brein. Waarom Swaab?

‘Toen ik met dit boek begon, zocht ik iemand om botweg te kunnen aanvallen. Van alle gekke neurowetenschappers is hij de radicaalste. Wetenschappers geloven dat objecten alleen maar materieel kunnen zijn, en bepaald worden door de wetten van de natuur. Maar hoe zit het dan met het bewustzijn? Neem koffie. We kunnen een definitie geven van de chemische samenstelling, maar niet van wat de smaak is van koffie. Hoe kun je van hetzelfde object, koffie, twee verschillende ervaringen hebben? Daarom denk ik dat het materialisme incompleet is.’

Wat maakt het uit dat we volgens u niet alleen maar ons brein zijn?

‘Om te beginnen dat het fout is. Als iemand gelooft dat er zoiets is als ťťn grootste getal, dan zouden we hem ook willen verbeteren, omdat hij uiteindelijk zijn wiskunde-examen niet zou halen. Verder is het probleem dat er veel Europees geld naar hersenonderzoek gaat dat is gebaseerd op een verkeerd idee van de geest en het brein. De neurowetenschap zou een puur medische functie moeten hebben, zoals het genezen van alzheimer, of om te bepalen of iemand in een coma toch een actief bewustzijn heeft. Het kan nooit antwoord geven op de metafysische vraag wat wij zijn. Het brein is een verzameling neuronen. Wetenschap kan laten zien hoe deze neuronen werken, en de psychologie kan de menselijke geest bestuderen. Tegelijkertijd zal die aanpak geen verklaring geven voor de relatie tussen het brein en de geest.

Waarom we vrij zijn als we denken - Filosofie van de geest voor de eenentwintigste eeuw

‘Gelukkig mag iedere filosoof wel eens een simpele oplossing gebruiken voor een moeilijk vraagstuk. Die van mij luidt als volgt. Stel: we willen een ander mens in dezelfde kamer waarnemen. Allereerst moeten we een brein hebben, met een bepaalde structuur. Niemand kan ontkennen dat het brein een noodzakelijke voorwaarde voor een bewustzijn is. Dat betekent niet dat dit genoeg is. Om in dezelfde kamer te zijn is ook een lichaam nodig dat het brein draagt, en de andere persoon die we waarnemen. Laat ik een vergelijking gebruiken die Nederlanders aan zal spreken. Wat is het verschil tussen een fiets en de handeling van het fietsen? Je hebt een fiets nodig om te kunnen fietsen, maar de handeling van het fietsen is niet hetzelfde als de fiets. De hersenen zijn de fiets, en onze geest is wat we doen met de fiets.”

Als we meer zijn dan ons brein, wat zijn we dan?

‘Ons bewustzijn is een zelfverklarende structuur. Het is geen hard natuurlijk gegeven zoals het feit dat water hetzelfde is als H2O. Mijn overtuiging over wat de Alpen zijn zal de Alpen nooit kunnen veranderen. Maar mijn overtuiging over wat ik ben zal wel veranderen wat ik ben. Daarin komt ook de vrijheid van ons denken naar voren. Bepaalde mensen geloven dat zij een onsterfelijke ziel hebben. Dat als zij zich op een bepaalde manier gedragen, zij misschien een groot huis krijgen in de hemel. Daarin ligt ook onze vrijheid als we denken: onze geest kan ons begrip van onszelf, en daarmee ons gedrag, veranderen; bij simpele objecten in de natuur kan dat niet.’

Volgens u is de filosofie van de geest, die volgens u vrij is, belangrijker dan ooit.

‘Als we ontkennen dat we vrij zijn, geven we indirect een rechtvaardiging voor het kwaad. Dan kan je bijvoorbeeld het klassieke excuus ‘ik was dronken’ gebruiken. Daarmee negeer je je eigen verantwoordelijkheid. Ik ben een pluralist. Uiteindelijk is het ieders verantwoordelijkheid om te beseffen dat wij allemaal vrij zijn in ons denken. Dat ons handelen niet alleen maar het gevolg is van simpele neurologische processen. De westerse materialist gelooft dat hij een metafysische waarheid heeft gevonden die hij moet verdedigen tegen gestoorde fundamentalisten uit het Midden-Oosten. Daar zit ook het politiek-sociale aspect dat ik met mijn boek wil overkomen. Onze wetenschap zal nooit het bewustzijn kunnen verklaren, en wij zullen dus nooit kunnen begrijpen wat zich in iemands bewustzijn afspeelt.’

(newscientist.nl)

‘Wetenschap zal nooit bewustzijn kunnen verklaren’

Hoe ons bewustzijn echt werkt? De wetenschap gaat het ons niet vertellen, betoogt de Duitse sterfilosoof Markus Gabriel. En passant opent hij de aanval op Dick Swaab, ‘de radicaalste van alle gekke neurowetenschappers’.

Markus Gabriel: ‘De neurowetenschap zou een puur medische functie moeten hebben.’ Bron: Flickr/neil conway

Op 29-jarige leeftijd werd Markus Gabriel aangesteld als jongste hoogleraar in de filosofie ooit aan de Universiteit Bonn. Met de reeks boeken die achter zijn naam staat, heeft de inmiddels 35-jarige zich gevestigd als titaan in de filosofie. Hij brak door met Waarom de wereld niet bestaat, waarin hij beargumenteerde dat alles wat wij ons kunnen verbeelden bestaat, zelfs eenhoorns – maar de wereld zelf niet, want daar kunnen wij ons geen voorstelling van maken. In zijn laatste werk Waarom we vrij zijn als we denken heeft Gabriel een nieuw slachtoffer gevonden: de neurowetenschap.

De Duitse titel van uw boek Ich ist nicht Gehirn (Ik is niet het brein) is afgeleid van Dick Swaabs Wij zijn ons brein. Waarom Swaab?

‘Toen ik met dit boek begon, zocht ik iemand om botweg te kunnen aanvallen. Van alle gekke neurowetenschappers is hij de radicaalste. Wetenschappers geloven dat objecten alleen maar materieel kunnen zijn, en bepaald worden door de wetten van de natuur. Maar hoe zit het dan met het bewustzijn? Neem koffie. We kunnen een definitie geven van de chemische samenstelling, maar niet van wat de smaak is van koffie. Hoe kun je van hetzelfde object, koffie, twee verschillende ervaringen hebben? Daarom denk ik dat het materialisme incompleet is.’

Wat maakt het uit dat we volgens u niet alleen maar ons brein zijn?

‘Om te beginnen dat het fout is. Als iemand gelooft dat er zoiets is als ťťn grootste getal, dan zouden we hem ook willen verbeteren, omdat hij uiteindelijk zijn wiskunde-examen niet zou halen. Verder is het probleem dat er veel Europees geld naar hersenonderzoek gaat dat is gebaseerd op een verkeerd idee van de geest en het brein. De neurowetenschap zou een puur medische functie moeten hebben, zoals het genezen van alzheimer, of om te bepalen of iemand in een coma toch een actief bewustzijn heeft. Het kan nooit antwoord geven op de metafysische vraag wat wij zijn. Het brein is een verzameling neuronen. Wetenschap kan laten zien hoe deze neuronen werken, en de psychologie kan de menselijke geest bestuderen. Tegelijkertijd zal die aanpak geen verklaring geven voor de relatie tussen het brein en de geest.

Waarom we vrij zijn als we denken - Filosofie van de geest voor de eenentwintigste eeuw

‘Gelukkig mag iedere filosoof wel eens een simpele oplossing gebruiken voor een moeilijk vraagstuk. Die van mij luidt als volgt. Stel: we willen een ander mens in dezelfde kamer waarnemen. Allereerst moeten we een brein hebben, met een bepaalde structuur. Niemand kan ontkennen dat het brein een noodzakelijke voorwaarde voor een bewustzijn is. Dat betekent niet dat dit genoeg is. Om in dezelfde kamer te zijn is ook een lichaam nodig dat het brein draagt, en de andere persoon die we waarnemen. Laat ik een vergelijking gebruiken die Nederlanders aan zal spreken. Wat is het verschil tussen een fiets en de handeling van het fietsen? Je hebt een fiets nodig om te kunnen fietsen, maar de handeling van het fietsen is niet hetzelfde als de fiets. De hersenen zijn de fiets, en onze geest is wat we doen met de fiets.”

Als we meer zijn dan ons brein, wat zijn we dan?

‘Ons bewustzijn is een zelfverklarende structuur. Het is geen hard natuurlijk gegeven zoals het feit dat water hetzelfde is als H2O. Mijn overtuiging over wat de Alpen zijn zal de Alpen nooit kunnen veranderen. Maar mijn overtuiging over wat ik ben zal wel veranderen wat ik ben. Daarin komt ook de vrijheid van ons denken naar voren. Bepaalde mensen geloven dat zij een onsterfelijke ziel hebben. Dat als zij zich op een bepaalde manier gedragen, zij misschien een groot huis krijgen in de hemel. Daarin ligt ook onze vrijheid als we denken: onze geest kan ons begrip van onszelf, en daarmee ons gedrag, veranderen; bij simpele objecten in de natuur kan dat niet.’

Volgens u is de filosofie van de geest, die volgens u vrij is, belangrijker dan ooit.

‘Als we ontkennen dat we vrij zijn, geven we indirect een rechtvaardiging voor het kwaad. Dan kan je bijvoorbeeld het klassieke excuus ‘ik was dronken’ gebruiken. Daarmee negeer je je eigen verantwoordelijkheid. Ik ben een pluralist. Uiteindelijk is het ieders verantwoordelijkheid om te beseffen dat wij allemaal vrij zijn in ons denken. Dat ons handelen niet alleen maar het gevolg is van simpele neurologische processen. De westerse materialist gelooft dat hij een metafysische waarheid heeft gevonden die hij moet verdedigen tegen gestoorde fundamentalisten uit het Midden-Oosten. Daar zit ook het politiek-sociale aspect dat ik met mijn boek wil overkomen. Onze wetenschap zal nooit het bewustzijn kunnen verklaren, en wij zullen dus nooit kunnen begrijpen wat zich in iemands bewustzijn afspeelt.’

(newscientist.nl)

Death Makes Angels of us all

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

And gives us wings where we had shoulders

Smooth as raven' s claws...

FREE SPEECH AND ISLAM - IN DEFENSE OF SAM HARRIS

written by Jeffrey Tayler

The controversial atheist needs a fair hearing

“It’s gross! It’s racist!” exclaimed Ben Affleck on Bill Maher’s Real Time in October 2014, interrupting the neuroscientist “New Atheist” Sam Harris.

Harris had been carefully explaining the linguistic bait-and-switch inherent in the word “Islamophobia” as “intellectually ridiculous,” in that “every criticism of the doctrine of Islam gets conflated with bigotry toward Muslims as people.” The result: progressives duped by the word shy away from criticizing the ideology of Islam, the tenets of which (including second-class status for women and intolerance toward sexual minorities) would, in any other context, surely elicit their condemnation.

Unwittingly, Affleck had confirmed Harris’ point, conflating religion with race. In doing so, the actor was espousing a position that can lead to a de facto racist conclusion. If you discount Islamic doctrine as the motivation for domestic violence and intolerance of sexual minorities in the Muslim world, you’re left with at least one implicitly bigoted assumption: the people of the region must then be congenitally inclined to behave as they do.

There was a disturbing irony in Affleck’s outburst. Few public intellectuals have done as thorough a job as Harris at pointing out the fallacies and dangers of the supernatural dogmas of religion, for which far too many are willing to kill and die these days. An avowed liberal (who plans to vote for Hillary) Harris is the author of, among many books, the groundbreaking The End of Faith. Yet Affleck seemed predisposed to regard him with hostility, possibly because Harris, at least for some on the Left, has acquired a toxic reputation — one stemming from what amounts to a campaign of defamation involving, by all appearances, a willful misrepresentation of his work, plus no small measure of slipshod “identity politics” thinking.

Harris has been lambasted as, among other things, a “genocidal fascist maniac” advocating “scientific racism,” militarism, and the murder of innocents for their beliefs, as well as racial profiling at airports, a nuclear first strike on the Middle East, plus, of course, Islamophobia and a failure to understand the faiths he argues against. (This is just a partial list.) The result? Harris has had to take measures to ensure his personal security, with negative ramifications in almost every area of his life. “I can say that much of what I do,” he told me in a recent email exchange, “both personally and professionally, is now done under a shadow of defamatory lies.”

The attacks against Harris have emanated predominantly from a prominent yet persistent handful of supposed progressives (and their peons), among whom are the religion scholar and media personality Reza Aslan, and the journalists from The Intercept, Glenn Greenwald (famed for transmitting Edward Snowden’s NSA revelations to the world) and Murtaza Hussain. Lately, with Harris’ publication of Islam and the Future of Tolerance, they have even taken aim at his coauthor and friend, the onetime Islamist turned reformer Maajid Nawaz.

Nonetheless, Harris’ own words, conveyed through his books, podcasts, blog posts, interviews, and Twitter feed, bely the attacks, which can be as mean-spirited as they are groundless and muddled. They have tainted the debates we need to conduct about Islam and terrorism in particular, but, more generally, the danger religious fundamentalism poses to our constitutionally secular republic and to the largely post-Christian countries of Western Europe now confronting huge inflows of Muslim migrants. The sum effect is to leave us all less well-off, less safe. And certainly more confused.

The charge of insufficient religious expertise is the least substantial, but nonetheless worth dispensing with, given that it could potentially be leveled at any nonbeliever disagreeing with faith’s precepts. In a 2007 debate, for instance, Reza Aslan accused Harris of having a “profoundly unsophisticated” view of religion, and of relying on Fox News as his “research tools” – an assertion that can be disproved by just opening The End of Faith, a meticulously compiled treatise with 237 pages of text (in the paperback edition) followed by sixty-one pages of footnotes and twenty-eight pages of bibliography listing some six hundred sources. In this opus, Harris walks us through the many follies of faith (mostly Christianity and Islam), but one key message transpires: belief guides behavior. A self-evident proposition no reasonable person would argue with.

Which has not stopped Reza Aslan from doing just that. Writing in relation to Harris’ skirmish with Affleck, Aslan has stated that religion “is often far more a matter of identity than it is a matter of beliefs and practices” and that “people of faith insert their values into their Scriptures,” with other, often contingent factors causing them to act as they do. So when ISIS guerrillas behead their captives, justifying their bloodshed by proclaiming jihad and citing verses from the Quran, by Aslan’s definition we cannot blame the doctrine of jihad or the contents of Islamic scripture, but must seek out other motives. This is prima facie obfuscatory, because it involves discounting the testimony of the perpetrators themselves.

The “genocidal fascist maniac” moniker was born of a certain @dan_verg_ on Twitter (account since suspended), and retweeted by Reza Aslan and Glenn Greenwald. The tweet misquoted, without context, a line from Harris’s The End of Faith: “Some beliefs” — “propositions” in the original — “are so dangerous that it may be ethical to kill people for believing them.” Which suggests Harris might endorse the death penalty for thought crime.