WGR Werk, Geldzaken, Recht en de Beurs

Hier kun je alles kwijt over sollicitaties, werksituaties, belastingen, (handelen op) de beurs, hypotheken, beleggingen en salarissen, arbeidscontracten of geschillen met je (huis)baas. Alles over werk, geldzaken en recht dus.

Bron: money.cnn.comquote:The $55 trillion question

The financial crisis has put a spotlight on the obscure world of credit default swaps - which trade in a vast, unregulated market that most people haven't heard of and even fewer understand. Will this be the next disaster?

By Nicholas Varchaver, senior editor and Katie Benner, writer-reporter

September 30, 2008: 5:38 AM ET

(Fortune Magazine) -- If Hieronymus Bosch were alive today to paint a triptych called "The Garden of Mortgage Delights," we'd recognize most of the characters in the bacchanalia and its hellish aftermath. Looming largest, of course, would be the Luciferian figures of Greed and Excessive Debt. Scurrying throughout would be the Wall Street bankers who turned these burgeoning debts into exotic securities with tangled structures and soporific acronyms - CDO, MBS, ABS - that concealed the dangers within. Needless to say, we'd see the smooth-tongued emissaries of the credit-rating agencies assuring people that assets of lead could indeed be transformed into investments of gold. Finally, somewhere past the feckless Fannie Mae executives and the dozing politicians, one final figure would lurk in the shadows: a hulking and barely recognizable monster known as Credit Default Swaps.

CDS are no mere artist's fancy. In just over a decade these privately traded derivatives contracts ballooned from nothing into a $54.6 trillion market. CDS are the fastest-growing major type of financial derivatives. More important, they've played a critical role in the unfolding financial crisis. First, by ostensibly providing "insurance" on risky mortgage bonds, they encouraged and enabled reckless behavior during the housing bubble. "If CDS had been taken out of play, companies would've said, 'I can't get this [risk] off my books,'" says Michael Greenberger, a University of Maryland law professor and former director of trading and markets at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. "If they couldn't keep passing the risk down the line, those guys would've been stopped in their tracks. The ultimate assurance for issuing all this stuff was, 'It's insured.'" Second, terror at the potential for a financial Ebola virus radiating out from a failing institution and infecting dozens or hundreds of other companies - all linked to one another by CDS and other instruments - was a major reason that regulators stepped in to bail out Bear Stearns and buy out AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), whose calamitous descent itself was triggered by losses on its CDS contracts (see "Hank's Last Stand").

And the fear of a CDS catastrophe still haunts the markets. For starters, nobody knows how federal intervention might ripple through this chain of contracts. And meanwhile, as we'll see, two fundamental aspects of the CDS market - that it is unregulated, and that almost nothing is disclosed publicly - may be about to change. That adds even more uncertainty to the equation. "The big problem is that here are all these public companies - banks and corporations - and no one really knows what exposure they've got from the CDS contracts," says Frank Partnoy, a law professor at the University of San Diego and former Morgan Stanley derivatives salesman who has been writing about the dangers of CDS and their ilk for a decade. "The really scary part is that we don't have a clue." Chris Wolf, a co-manager of Cogo Wolf, a hedge fund of funds, compares them to one of the great mysteries of astrophysics: "This has become essentially the dark matter of the financial universe."

***

AT FIRST GLANCE, credit default swaps don't look all that scary. A CDS is just a contract: The "buyer" plunks down something that resembles a premium, and the "seller" agrees to make a specific payment if a particular event, such as a bond default, occurs. Used soberly, CDS offer concrete benefits: If you're holding bonds and you're worried that the issuer won't be able to pay, buying CDS should cover your loss. "CDS serve a very useful function of allowing financial markets to efficiently transfer credit risk," argues Sunil Hirani, the CEO of Creditex, one of a handful of marketplaces that trade the contracts.

Because they're contracts rather than securities or insurance, CDS are easy to create: Often deals are done in a one-minute phone conversation or an instant message. Many technical aspects of CDS, such as the typical five-year term, have been standardized by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). That only accelerates the process. You strike your deal, fill out some forms, and you've got yourself a $5 million - or a $100 million - contract.

And as long as someone is willing to take the other side of the proposition, a CDS can cover just about anything, making it the Wall Street equivalent of those notorious Lloyds of London policies covering Liberace's hands and other esoterica. It has even become possible to purchase a CDS that would pay out if the U.S. government defaults. (Trust us when we say that if the government goes under, trying to collect will be the least of your worries.)

You can guess how Wall Street cowboys responded to the opportunity to make deals that (1) can be struck in a minute, (2) require little or no cash upfront, and (3) can cover anything. Yee-haw! You can almost picture Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove climbing onto the H-bomb before it's released from the B-52. And indeed, the volume of CDS has exploded with nuclear force, nearly doubling every year since 2001 to reach a recent peak of $62 trillion at the end of 2007, before receding to $54.6 trillion as of June 30, according to ISDA.

Take that gargantuan number with a grain of salt. It refers to the face value of all outstanding contracts. But many players in the market hold offsetting positions. So if, in theory, every entity that owns CDS had to settle its contracts tomorrow and "netted" all its positions against each other, a much smaller amount of money would change hands. But even a tiny fraction of that $54.6 trillion would still be a daunting sum.

The credit freeze and then the Bear disaster explain the drop in outstanding CDS contracts during the first half of the year - and the market has only worsened since. CDS contracts on widely held debt, such as General Motors' (GM, Fortune 500), continue to be actively bought and sold. But traders say almost no new contracts are being written on any but the most liquid debt issues right now, in part because nobody wants to put money at risk and because nobody knows what Washington will do and how that will affect the market. ("There's nothing to do but watch Bernanke on TV," one trader told Fortune during the week when the Fed chairman was going before Congress to push the mortgage bailout.) So, after nearly a decade of exponential growth, the CDS market is poised for its first sustained contraction.

***

ONE REASON THE MARKET TOOK OFF is that you don't have to own a bond to buy a CDS on it - anyone can place a bet on whether a bond will fail. Indeed the majority of CDS now consists of bets on other people's debt. That's why it's possible for the market to be so big: The $54.6 trillion in CDS contracts completely dwarfs total corporate debt, which the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association puts at $6.2 trillion, and the $10 trillion it counts in all forms of asset-backed debt. "It's sort of like I think you're a bad driver and you're going to crash your car," says Greenberger, formerly of the CFTC. "So I go to an insurance company and get collision insurance on your car because I think it'll crash and I'll collect on it." That's precisely what the biggest winners in the subprime debacle did. Hedge fund star John Paulson of Paulson & Co., for example, made $15 billion in 2007, largely by using CDS to bet that other investors' subprime mortgage bonds would default.

So what started out as a vehicle for hedging ended up giving investors a cheap, easy way to wager on almost any event in the credit markets. In effect, credit default swaps became the world's largest casino. As Christopher Whalen, a managing director of Institutional Risk Analytics, observes, "To be generous, you could call it an unregulated, uncapitalized insurance market. But really, you would call it a gaming contract."

There is at least one key difference between casino gambling and CDS trading: Gambling has strict government regulation. The federal government has long shied away from any oversight of CDS. The CFTC floated the idea of taking an oversight role in the late '90s, only to find itself opposed by Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and others. Then, in 2000, Congress, with the support of Greenspan and Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, passed a bill prohibiting all federal and most state regulation of CDS and other derivatives. In a press release at the time, co-sponsor Senator Phil Gramm - most recently in the news when he stepped down as John McCain's campaign co-chair this summer after calling people who talk about a recession "whiners" - crowed that the new law "protects financial institutions from over-regulation ... and it guarantees that the United States will maintain its global dominance of financial markets." (The authors of the legislation were so bent on warding off regulation that they had the bill specify that it would "supersede and preempt the application of any state or local law that prohibits gaming ...") Not everyone was as sanguine as Gramm. In 2003 Warren Buffett famously called derivatives "financial weapons of mass destruction."

***

THERE'S ANOTHER BIG difference between trading CDS and casino gambling. When you put $10 on black 22, you're pretty sure the casino will pay off if you win. The CDS market offers no such assurance. One reason the market grew so quickly was that hedge funds poured in, sensing easy money. And not just big, well-established hedge funds but a lot of upstarts. So in some cases, giant financial institutions were counting on collecting money from institutions only slightly more solvent than your average minimart. The danger, of course, is that if a hedge fund suddenly has to pay off on a lot of CDS, it will simply go out of business. "People have been insuring risks that they can't insure," says Peter Schiff, the president of Euro Pacific Capital and author of Crash Proof, which predicted doom for Fannie and Freddie, among other things. "Let's say you're writing fire insurance policies, and every time you get the [premium], you spend it. You just assume that no houses are going to burn down. And all of a sudden there's a huge fire and they all burn down. What do you do? You just close up shop."

This is not an academic concern. Wachovia (WB, Fortune 500) and Citigroup (C, Fortune 500) are wrangling in court with a $50 million hedge fund located in the Channel Islands. The reason: A dispute over two $10 million credit default swaps covering some CDOs. The specifics of the spat aren't important. What's most revealing is that these massive banks put their faith in a Lilliputian fund (in an inaccessible jurisdiction) that was risking 40% of its capital for just two CDS. Can anyone imagine that Citi would, say, insure its headquarters building with a thinly capitalized, unregulated, offshore entity?

That's one element of what's known as "counterparty risk." Here's another: In many cases, you don't even know who has the other side of your bet. Parties to the contract can, and do, transfer their side of the contract to third parties. Investment firms assert that transfers are well documented (a claim that, like most in the world of CDS, is impossible to verify). But even if that's true, you're still left with the fact that a given company's risks are being dispersed in ways that they may not know about and can't control.

It doesn't help that CDS trading is a haphazard process. Most contracts are bought and sold over the phone or by instant message and settled manually. Settlement has been sloppy, confirms Jamie Cawley of IDX Capital, a firm that brokers trades between big banks. Pushed by New York Fed president Timothy Geithner, the players have been improving the process. But even as recently as a year ago, Cawley says, so many trades were sitting around unfulfilled that "there were $1 trillion worth of swaps that were unsettled among counterparties."

Trade settlement is not the only anachronistic aspect of CDS trading. Consider what will happen with CDS contracts relating to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The two were placed in conservatorship on Sept. 7. But the value of many contracts won't be determined till Oct. 6, when an auction will set a cash price for Fannie and Freddie bonds. We'll spare you the technical reasons, but suffice it to ask: Can you imagine any other major market that would need a month to resolve something like this?

***

WITH WASHINGTON SUDDENLY in a frenzy of outrage over the financial markets, debating everything from the shape and extent of the mortgage plan to what should be done about short-selling, the future for CDS is very blurry. "The market is here to stay," asserts Cawley. The question is simply: What sorts of changes are in store? As this article was going to press, SEC chairman Christopher Cox asked the Senate to allow his agency to begin regulating CDS - mostly, it should be said, to rein in short-selling. And the SEC separately announced that it was expanding its investigation of market manipulation, which initially targeted the short-sellers, to CDS investors.

Under other circumstances, Cox's request might have been met with polite silence. But the convulsions over the mortgage bailout are so dramatic that they are reminiscent of the moment, soon after the Enron scandal, when Congress drafted the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation. The desire to blame short-sellers may actually result in powers for Cox that, until very recently, he showed no signs of wanting. Should legislators wade into this issue, the measures most widely seen as necessary are straightforward: some form of centralized trading or clearing and some form of capital or reserve requirements. Meanwhile, New York State's insurance commissioner, Eric Dinallo, announced new regulations that would essentially treat sellers of some (but not all) CDS as insurance entities, thereby forcing them to set aside reserves and otherwise follow state insurance law - requirements that would probably drive many participants from the market. Whether CDS players will find a way to challenge the rules remains to be seen. (ISDA, the industry's trade group, has already gone on record in opposition to Cox's proposal.) If nothing else, the New York law may provide additional impetus for the feds to take action.

For now, the biggest impact could come from the Financial Accounting Standards Board. It is implementing a new rule in November that will require sellers of CDS and other credit derivatives to report detailed information, including their maximum payouts and reasons for entering the contracts, as well as assets that might allow them to offset any payouts. Anybody who has tried to parse CEO compensation in recent years knows that more disclosure doesn't guarantee clarity, but any increase in information in the CDS realm will be a benefit. Perhaps that would limit the baleful effect of CDS on (must we consider it?) the next disaster - or even help us prevent it.

Kan iemand mij zeggen hoe groot dat kaartenhuis is dat men heeft opgebouwd?

Op woensdag 24 sept. 2008 schreef Danny het volgende:

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Op woensdag 24 sept. 2008 schreef Danny het volgende:

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Ik kom niet door die droge tekst heen hoor, kun je niet ff een samenvatting geven?  .

.

I am so clever that sometimes I don't understand a single word of what I am saying.

quote:"It's sort of like I think you're a bad driver and you're going to crash your car," says Greenberger, formerly of the CFTC. "So I go to an insurance company and get collision insurance on your car because I think it'll crash and I'll collect on it." That's precisely what the biggest winners in the subprime debacle did. Hedge fund star John Paulson of Paulson & Co., for example, made $15 billion in 2007, largely by using CDS to bet that other investors' subprime mortgage bonds would default.

Dat is wel een goede samenvatting denk ik zo.quote:You can guess how Wall Street cowboys responded to the opportunity to make deals that (1) can be struck in a minute, (2) require little or no cash upfront, and (3) can cover anything. Yee-haw! You can almost picture Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove climbing onto the H-bomb before it's released from the B-52. And indeed, the volume of CDS has exploded with nuclear force, nearly doubling every year since 2001 to reach a recent peak of $62 trillion at the end of 2007, before receding to $54.6 trillion as of June 30, according to ISDA.

Op woensdag 24 sept. 2008 schreef Danny het volgende:

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

A zegt tegen B: ik geef jou x geld, als het fout gaat dan krijg ik van jou xxxxxxxx geld.

En nu is de tegenprestatie vele malen hoger dan dat er sowieso geld is. Uiteindelijk zal het wel minder zijn omdat A met C een deal sluit waarbij C A geld geeft en van A dan geld zou krijgen als het fout gaat.

En B dan ook zo'n deal sluit met C. Je kan dus een heleboel tegen elkaar wegstrepen. Maar er blijft ook nog enorm veel over.

En nu is de tegenprestatie vele malen hoger dan dat er sowieso geld is. Uiteindelijk zal het wel minder zijn omdat A met C een deal sluit waarbij C A geld geeft en van A dan geld zou krijgen als het fout gaat.

En B dan ook zo'n deal sluit met C. Je kan dus een heleboel tegen elkaar wegstrepen. Maar er blijft ook nog enorm veel over.

Op woensdag 24 sept. 2008 schreef Danny het volgende:

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Dagonet doet onaardig tegen iedereen. Je bent dus helemaal niet zo bijzonder als je denkt...

Mijn grootste bijdrage aan de FP.

Ten eerste wil ik even melden dat het een interessant artikel is en dat de gewone burger hier zich beter niet het hoofd aan kan stoten om het te willen begrijpen.

Het is gewoon gokken om groot geld en sommigen zijn er beter in dan anderen.

De bubble is wel aanwezig, maar meer in de zin van het feit dat niemand een overzicht heeft wie aan wie geld verschuldigd is als er een bedrijf falliet gaat. In de huidige markt is het enorm gevaarlijk om een dergelijke CDS aan te gaan en dat gebeurd gelukkig ook niet veel meer, maar er zijn er nog een heleboel die al afgesloten zijn. Nu er grote bedrijven falliet gaan is het de vraag of iedereen zijn CDO schulden kan gaan afbetalen en eerlijk gezegt denk ik niet dat dat het geval is. Dat zou betekenen dat de gevolgen van een eventueel falliesement van een bank gigantische onverwachte gevolgen kan hebben voor andere zwaargewichten en die kunnen op hun beurt weer in de problemen komen en zo een dominoeffect veroorzaken.

Het bovenstaande is een versimpelde verklaring, maar de vrees is volkomen terecht.

Ik werk op dit moment in Londen en ben verantwoordelijk voor de administratie, waardering en rapportage van speciaal opgezette bedrijven (SPV's; special purpose vehicles) die dergelijke financiele transacties bevatten.

Mocht je dus meer vragen hebben en diepgang wilt, laat het maar weten

Het is gewoon gokken om groot geld en sommigen zijn er beter in dan anderen.

De bubble is wel aanwezig, maar meer in de zin van het feit dat niemand een overzicht heeft wie aan wie geld verschuldigd is als er een bedrijf falliet gaat. In de huidige markt is het enorm gevaarlijk om een dergelijke CDS aan te gaan en dat gebeurd gelukkig ook niet veel meer, maar er zijn er nog een heleboel die al afgesloten zijn. Nu er grote bedrijven falliet gaan is het de vraag of iedereen zijn CDO schulden kan gaan afbetalen en eerlijk gezegt denk ik niet dat dat het geval is. Dat zou betekenen dat de gevolgen van een eventueel falliesement van een bank gigantische onverwachte gevolgen kan hebben voor andere zwaargewichten en die kunnen op hun beurt weer in de problemen komen en zo een dominoeffect veroorzaken.

Het bovenstaande is een versimpelde verklaring, maar de vrees is volkomen terecht.

Ik werk op dit moment in Londen en ben verantwoordelijk voor de administratie, waardering en rapportage van speciaal opgezette bedrijven (SPV's; special purpose vehicles) die dergelijke financiele transacties bevatten.

Mocht je dus meer vragen hebben en diepgang wilt, laat het maar weten

“Snowboarding is an activity that is very popular with people who do not feel that regular skiing is lethal enough.”

Lehman brothers is nog steeds de eerste bank die ze volledig failliet hebben laten gaan als een testcase.

En ja Lehamn bezat een boel derivaten wat nu als een fail-out nog afgeboekt moet worden.

De swaps waar het hier om gaat worden in sneltrein afgebouwd. Beleggingsbanken transformeren weer langzaam in Spaarbanken of in genationaliseerde instituten.

De grootste player in dit spel was no doubt AIG, want die gaf meestal de tegenprestatie weg (als het fout ging). Maar AIG heeft uitstel van executie en zal langzaam verdwijnen van het toneel.

De hele CDS markt valt op dit moment stil. Omdat er geen sprake meer is van een absolute waarborg. Het is nu nog slechts een papieren belofte.

Wie hebben die dingen gekocht..... zowat hele wereld... ook onze banken, pensioenfondsen zitten er diep in.

De echte pijn voelen we pas (veel) later....maar we gaan hem voelen (daar twijfel ik niet aan)

En ja Lehamn bezat een boel derivaten wat nu als een fail-out nog afgeboekt moet worden.

De swaps waar het hier om gaat worden in sneltrein afgebouwd. Beleggingsbanken transformeren weer langzaam in Spaarbanken of in genationaliseerde instituten.

De grootste player in dit spel was no doubt AIG, want die gaf meestal de tegenprestatie weg (als het fout ging). Maar AIG heeft uitstel van executie en zal langzaam verdwijnen van het toneel.

De hele CDS markt valt op dit moment stil. Omdat er geen sprake meer is van een absolute waarborg. Het is nu nog slechts een papieren belofte.

Wie hebben die dingen gekocht..... zowat hele wereld... ook onze banken, pensioenfondsen zitten er diep in.

De echte pijn voelen we pas (veel) later....maar we gaan hem voelen (daar twijfel ik niet aan)

Volgens mij blijft er in veel gevallen helemaal niks over, omdat partijen hun uitstaande schuld niet kunnen betalen, terwijl deze schulden wel als bezittingen op de balans van de eisende partij staan.quote:Op dinsdag 30 september 2008 13:44 schreef Dagonet het volgende:

A zegt tegen B: ik geef jou x geld, als het fout gaat dan krijg ik van jou xxxxxxxx geld.

En nu is de tegenprestatie vele malen hoger dan dat er sowieso geld is. Uiteindelijk zal het wel minder zijn omdat A met C een deal sluit waarbij C A geld geeft en van A dan geld zou krijgen als het fout gaat.

En B dan ook zo'n deal sluit met C. Je kan dus een heleboel tegen elkaar wegstrepen. Maar er blijft ook nog enorm veel over.

Resultaat: enorme afschrijvingen en als het een beetje tegenzit; nog meer faillissementen. Een soort Domino D-Day, maar dan anders.

Big dick.

TVp.

Ik in een aantal worden omschreven: Ondernemend | Moedig | Stout | Lief | Positief | Intuïtief | Communicatief | Humor | Creatief | Spontaan | Open | Sociaal | Vrolijk | Organisator | Pro-actief | Meedenkend | Levensgenieter | Spiritueel

Kick....

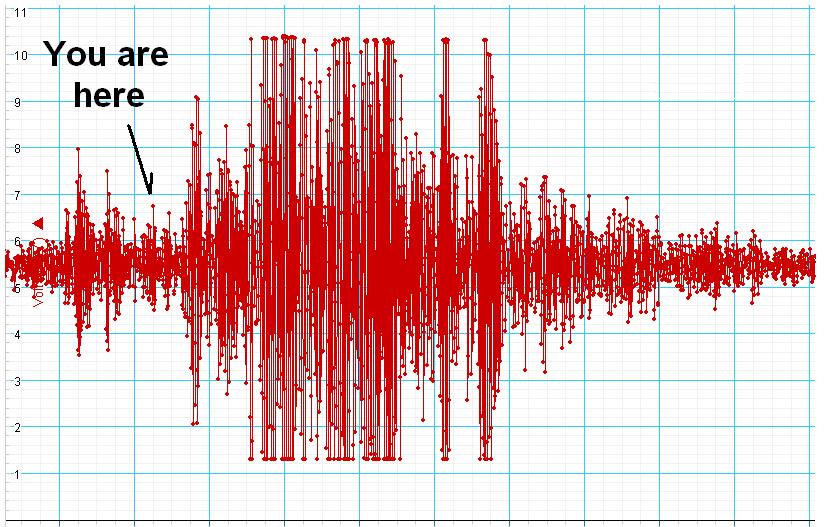

Deze maand stress-testen.

Deze maand stress-testen.

quote:Derivatives market faces biggest test

Published: September 30 2008 16:17 | Last updated: September 30 2008 22:38

The $54,000bn credit derivatives market faces its biggest test in October as billions of dollars worth of contracts on now-defaulted derivatives on Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual are settled.

Highlighting the opacity of this market, it is still not clear how many contracts have to be settled, and whether payouts on the defaulted contracts, which could reach billions of dollars, are concentrated with any particular institutions.

According to dealers, insurance companies and investors such as sovereign wealth funds, which are widely believed to have written large amounts of credit protection through credit default swaps on financial institutions, could have to pay out huge amounts.

“There is a lot at stake,” said an executive at one big dealer. “This is a crisis time, and if these auctions do not go well, or if the amounts investors and dealers have to pay is seen as not being fair, it could have further negative repercussions on the CDS market.”

The “auction season” starts on Thursday, when the International Swaps and Derivatives Association has scheduled an auction for Tembec, a Canadian forest products company.

”This is a tried and tested process that we expect to run as seamlessly for these larger scale events as it did for the last nine credit events ISDA helped settle smoothly,” said Robert Pickel, chief executive officer of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

This is followed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac auctions on October 6. Then, Lehman is settled on October 10, and Washington Mutual is scheduled for October 23.

Even though it is possible that some participants in the credit derivatives market will have to make large pay-outs, the flipside is there could also be big winners. For every loss in credit derivatives, there is a gain.

The amount of credit derivatives contracts outstanding that reference Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac alone are estimated to be up to $500bn. The default was triggered under the terms of derivatives contracts by the US government’s seizure of the mortgage groups, even though the underlying debt is strong after the explicit guarantee from the US government.

The CDS contract settlement could result in billions of dollars of losses for insurance companies and banks who offered credit insurance in recent months. The recovery value will be set by an auction process. Usually, the bond that is eligible for the auction that trades at the lowest price – the so-called cheapest-to-deliver – is the one that sets the overall recovery value for the credit derivatives.

In the Lehman case, numerous banks and investors have already made losses due to exposure to Lehman as a counterparty on numerous derivatives trades. The auctions next week are for credit derivatives which have Lehman as a reference entity. There are likely to be fewer contracts outstanding than for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac because Lehman was not included in many of the benchmark credit derivatives. However, exposure remains unclear, which is one concern that regulators now have about the credit derivatives market.

Lehman’s bonds have been trading between 15 and 19 cents on the dollar, meaning that investors who wrote protection on a Lehman default will have to pay out between 81 and 85 cents on the dollar, a relatively high payout.

The previous biggest default in credit derivatives was for Delphi, the US car parts maker that went bankrupt in 2005 and which had about $25bn of CDS.

quote:Op dinsdag 30 september 2008 14:04 schreef soylent het volgende:

TVp.

Never in the entire history of calming down did anyone ever calm down after being told to calm down.

Een Credit Default Swap (CDS) is eigenlijk niets meer dan een verzekering voor het failliet gaan van je tegenpartij. Op het moment dat je dus een positie hebt (je hebt bijvoorbeeld een obligatie gekocht) met een partij A, dan kun je die positie laten verzekeren door partij B. De prijs voor een CDS van partij A die je hiervoor moet betalen geeft goed aan hoe waarschijnlijk de markt een faillisement van partij A inschat.

Zo raar is dit product dus niet, en het is ook best logisch dat deze markt zo groot is. Immers, iedereen die investering heeft (denk bvb ook aan pensioenfondsen), maakt gebruik van deze producten. In het algemeen is de debt market veel groter dan de equity market, ook al heeft deze minder exposure op bvb rtl Z.

Zo raar is dit product dus niet, en het is ook best logisch dat deze markt zo groot is. Immers, iedereen die investering heeft (denk bvb ook aan pensioenfondsen), maakt gebruik van deze producten. In het algemeen is de debt market veel groter dan de equity market, ook al heeft deze minder exposure op bvb rtl Z.

quote:Waves of Credit Default Swaps Incoming

Have you wondered why the Treasury asked for a $700 Bn emergency package with the full force of the Fed behind them, and gave the Congress less than a week to deliver it?

Either these fellows have lost their nerve or the markets are riding to a fall, and it could be terrific.

We've been looking for some event, something that would have created such an extraordinary set of actions as we have seen in the past few days.

This just might be it. Special thanks to Yves Smith for flagging it.

Time to start settling those Credit Default Swaps for Fannie and Freddie (Oct. 6), Lehman Brothers (Oct. 10) and Lehman Brothers (Oct 23).

LIBOR is eight standard deviations from the norm, because the banks don't know who is holding what in their cards, but there might be some Aces and Eights in there. The TED spread is at an all time record high.

An insurance company is said to be heavily exposed.

Do you need to buy a vowel? Let's hope we get lucky.

Brace for impact.

Aegon de volgende nationalisatie dus of zal Bos geen boodschap hebben aan een omvallend verzekeringsbedrijf?

Wordt er bij een swap alleen betaald (geruild) na het verstrijken van de termijn van het contract of in geval van failure bij een credit swap?quote:Op dinsdag 30 september 2008 13:41 schreef Dagonet het volgende:

[..]

[..]

Dat is wel een goede samenvatting denk ik zo.

I´m back.

Het is mij nog even onduidelijk hoe dit in zijn werk gaat, er staat dat er een auction process bij te pas komt. Ik ging ervan uit dat een cds aldus werkte. A leent 1 miljoen dollar bij B. B wil zich indekken in geval A rente en aflossing niet kan betalen. Hij betaalt aan een verzekeraar 0,1 miljoen dollar, die in geval van failure van A daarvoor 1 miljoen dollar betaalt aan B. B krijgt dus altijd 0,9 miljoen netto terug.quote:Op vrijdag 3 oktober 2008 13:16 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

Kick....

Deze maand stress-testen.

[..]

Waarom komt er nu ineens een auction bij te pas? Of worden op die auction beide poten van de transactie pas geregeld?

I´m back.

Kan van alles zijn.... het is een afgeleid product.quote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:15 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

[..]

Wordt er bij een swap alleen betaald (geruild) na het verstrijken van de termijn van het contract of in geval van failure bij een credit swap?

Een soort Lloyds van Londen (waar je van alles en nog wat kunt verzekeren), maar dan als verkoopproduct voor de financiële instellingen. AIG zit er in ieder geval heel diep in.

En reken maar dat een boel 'slimme beleggers' hun producten een beetje fatsoenlijk afgeschermd hebben.

En deze maand is het pay-day. 3 van de 'big' five bestaan niet meer.

Ik vermoed idd zoiets... dit is voor mij onbekend terrein.quote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:30 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

Waarom komt er nu ineens een auction bij te pas? Of worden op die auction beide poten van de transactie pas geregeld?

Wat ik begrepen heb is, dat de swaps vooral gebruikt worden om renteschommelingen op te vangen. Maar in deze gevallen zal het idd gaan om subprime loans, schat ik in, of paketten daarvan. Die dus bij een verzekeraar zijn geswapt door in dit geval Lehmans bijv. In principe is deze setting dus gunstig voor Lehmans.quote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:32 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

Kan van alles zijn.... het is een afgeleid product.Omvallen van een bedrijf. Wanbetaler zo zot wat je verder nog kunt bedenken.

Maar wrs heeft Lehmans ook gefungeerd als verzekeraar bij andere swaps?

[ Bericht 3% gewijzigd door Ryan3 op 05-10-2008 00:47:31 ]

I´m back.

Hangt er een beetje vanaf wat in de prospectus staatquote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:40 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

[..]

Wat ik begrepen heb is, dat de swaps vooral gebruikt worden om renteschommelingen op te vangen. Maar in deze gevallen zal het idd gaan om subprime loans, schat ik in, of paketten daarvan. Die dus bij een verzekeraar zijn geswapt door in dit geval Lehmans bijv. In principe is deze setting dus gunstig voor Lehmans.

We zullen het wellicht maandag weten ...ik verwacht toch wel een beetje sensatie deze maand.

Boze tongen gaan zelfs zover dat de bail-out ervoor bedoeld is om buitenlandse investeerders te beschermen (d.m.v. het oppoetsen van de verzekeringsbalans)

Die laatste moet je even uitleggen, die begrijp ik niet.quote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:48 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

Hangt er een beetje vanaf wat in de prospectus staat

We zullen het wellicht maandag weten ...ik verwacht toch wel een beetje sensatie deze maand.

Boze tongen gaan zelfs zover dat de bail-out ervoor bedoeld is om buitenlandse investeerders te beschermen (d.m.v. het oppoetsen van de verzekeringsbalans)

We weten gewoon niet wat er op de balans staat van pensioenfondsen die in de VS hebben geïnvesteerd hè.

I´m back.

AIG Bail-out van 85 miljardquote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:54 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

[..]

Die laatste moet je even uitleggen, die begrijp ik niet.

We weten gewoon niet wat er op de balans staat van pensioenfondsen die in de VS hebben geïnvesteerd hè.

En wordt beweerd dat de nieuwe bail-out van 750 miljard (FED spaarpotje) ook een beetje bedoeld is om AIG te helpen.

Ah, op die manier.quote:Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 01:03 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

AIG Bail-out van 85 miljard

En wordt beweerd dat de nieuwe bail-out van 750 miljard (FED spaarpotje) ook een beetje bedoeld is om AIG te helpen.

Hier staat de kern van het probleem trouwens:

quote:AIG decided to get into this market a few years ago, and quickly became one of the biggest players. But they didn’t fully understand the risks associated with this market, and looked at it the same way they looked at homeowners insurance; figuring that they just needed to sell a lot of insurance policies so that a loss of one home would be made up by the premiums earned on all of the other homes. But a fire at one home typically doesn’t spread to all other homes, while a default by one bond issuer quickly turns into problems for other bond issuers.

I´m back.

In de derivatenhandel gaan sws onvoorstelbare bedragen om hè (van wikipedia, cijfers uit 2005):

Total derivatives (notional amount): $96.2 trillion (September, 2005)

Interest rate contracts: $82.0 trillion

Foreign exchange contracts: $8.6 trillion

Total number of commercial banks holding derivatives: 769

Total derivatives (notional amount): $96.2 trillion (September, 2005)

Interest rate contracts: $82.0 trillion

Foreign exchange contracts: $8.6 trillion

Total number of commercial banks holding derivatives: 769

I´m back.

Een interessante toevoeging aan dit topic: http://www.globalresearch.ca/index.php?context=va&aid=8634

Is relatief 'oud' (11 april 2008), maar zeer relevant.

Paar quotes:

Is relatief 'oud' (11 april 2008), maar zeer relevant.

Paar quotes:

quote:Credit default swaps are the most widely traded form of credit derivative. They are bets between two parties on whether or not a company will default on its bonds. In a typical default swap, the “protection buyer” gets a large payoff if the company defaults within a certain period of time, while the “protection seller” collects periodic payments for assuming the risk of default.

[...]

A Parade of Bailout Schemes

Now that some highly leveraged banks and hedge funds have had to lay their cards on the table and expose their worthless hands, these avid free marketers are crying out for government intervention to save them from monumental losses, while preserving the monumental gains raked in when their bluff was still good. In response to their pleas, the men behind the curtain have scrambled to devise various bailout schemes; but the schemes have been bandaids at best. To bail out a $681 trillion derivative scheme with taxpayer money is obviously impossible. As Michael Panzer observed on SeekingAlpha.com:

As the slow-motion train wreck in our financial system continues to unfold, there are going to be plenty of ill-conceived rescue attempts and dubious turnaround plans, as well as propagandizing, dissembling and scheming by banks, regulators and politicians. This is all happening in an effort to try and buy time or to figure out how the losses can be dumped onto the lap of some patsy (e.g., the taxpayer).

[...]

The banks will therefore no doubt be looking for one bailout after another from the only pocket deeper than their own, the U.S. government's. But if the federal government acquiesces, it too could be dragged into the voracious debt cyclone of the mortgage mess. The federal government's triple A rating is already in jeopardy, due to its gargantuan $9 trillion debt. Before the government agrees to bail out the banks, it should insist on some adequate quid pro quo. In England, the government agreed to bail out bankrupt mortgage bank Northern Rock, but only in return for the bank's stock. On March 31, 2008, The London Daily Telegraph reported that Federal Reserve strategists were eyeing the nationalizations that saved Norway, Sweden and Finland from a banking crisis from 1991 to 1993. In Norway, according to one Norwegian adviser, “The law was amended so that we could take 100 percent control of any bank where its equity had fallen below zero.”6 If their assets were “marked to market,” some major Wall Street banks could already be in that category.

|

|