quote:Bron: money.cnn.comThe $55 trillion question

The financial crisis has put a spotlight on the obscure world of credit default swaps - which trade in a vast, unregulated market that most people haven't heard of and even fewer understand. Will this be the next disaster?

By Nicholas Varchaver, senior editor and Katie Benner, writer-reporter

September 30, 2008: 5:38 AM ET

(Fortune Magazine) -- If Hieronymus Bosch were alive today to paint a triptych called "The Garden of Mortgage Delights," we'd recognize most of the characters in the bacchanalia and its hellish aftermath. Looming largest, of course, would be the Luciferian figures of Greed and Excessive Debt. Scurrying throughout would be the Wall Street bankers who turned these burgeoning debts into exotic securities with tangled structures and soporific acronyms - CDO, MBS, ABS - that concealed the dangers within. Needless to say, we'd see the smooth-tongued emissaries of the credit-rating agencies assuring people that assets of lead could indeed be transformed into investments of gold. Finally, somewhere past the feckless Fannie Mae executives and the dozing politicians, one final figure would lurk in the shadows: a hulking and barely recognizable monster known as Credit Default Swaps.

CDS are no mere artist's fancy. In just over a decade these privately traded derivatives contracts ballooned from nothing into a $54.6 trillion market. CDS are the fastest-growing major type of financial derivatives. More important, they've played a critical role in the unfolding financial crisis. First, by ostensibly providing "insurance" on risky mortgage bonds, they encouraged and enabled reckless behavior during the housing bubble. "If CDS had been taken out of play, companies would've said, 'I can't get this [risk] off my books,'" says Michael Greenberger, a University of Maryland law professor and former director of trading and markets at the Commodity Futures Trading Commission. "If they couldn't keep passing the risk down the line, those guys would've been stopped in their tracks. The ultimate assurance for issuing all this stuff was, 'It's insured.'" Second, terror at the potential for a financial Ebola virus radiating out from a failing institution and infecting dozens or hundreds of other companies - all linked to one another by CDS and other instruments - was a major reason that regulators stepped in to bail out Bear Stearns and buy out AIG (AIG, Fortune 500), whose calamitous descent itself was triggered by losses on its CDS contracts (see "Hank's Last Stand").

And the fear of a CDS catastrophe still haunts the markets. For starters, nobody knows how federal intervention might ripple through this chain of contracts. And meanwhile, as we'll see, two fundamental aspects of the CDS market - that it is unregulated, and that almost nothing is disclosed publicly - may be about to change. That adds even more uncertainty to the equation. "The big problem is that here are all these public companies - banks and corporations - and no one really knows what exposure they've got from the CDS contracts," says Frank Partnoy, a law professor at the University of San Diego and former Morgan Stanley derivatives salesman who has been writing about the dangers of CDS and their ilk for a decade. "The really scary part is that we don't have a clue." Chris Wolf, a co-manager of Cogo Wolf, a hedge fund of funds, compares them to one of the great mysteries of astrophysics: "This has become essentially the dark matter of the financial universe."

***

AT FIRST GLANCE, credit default swaps don't look all that scary. A CDS is just a contract: The "buyer" plunks down something that resembles a premium, and the "seller" agrees to make a specific payment if a particular event, such as a bond default, occurs. Used soberly, CDS offer concrete benefits: If you're holding bonds and you're worried that the issuer won't be able to pay, buying CDS should cover your loss. "CDS serve a very useful function of allowing financial markets to efficiently transfer credit risk," argues Sunil Hirani, the CEO of Creditex, one of a handful of marketplaces that trade the contracts.

Because they're contracts rather than securities or insurance, CDS are easy to create: Often deals are done in a one-minute phone conversation or an instant message. Many technical aspects of CDS, such as the typical five-year term, have been standardized by the International Swaps and Derivatives Association (ISDA). That only accelerates the process. You strike your deal, fill out some forms, and you've got yourself a $5 million - or a $100 million - contract.

And as long as someone is willing to take the other side of the proposition, a CDS can cover just about anything, making it the Wall Street equivalent of those notorious Lloyds of London policies covering Liberace's hands and other esoterica. It has even become possible to purchase a CDS that would pay out if the U.S. government defaults. (Trust us when we say that if the government goes under, trying to collect will be the least of your worries.)

You can guess how Wall Street cowboys responded to the opportunity to make deals that (1) can be struck in a minute, (2) require little or no cash upfront, and (3) can cover anything. Yee-haw! You can almost picture Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove climbing onto the H-bomb before it's released from the B-52. And indeed, the volume of CDS has exploded with nuclear force, nearly doubling every year since 2001 to reach a recent peak of $62 trillion at the end of 2007, before receding to $54.6 trillion as of June 30, according to ISDA.

Take that gargantuan number with a grain of salt. It refers to the face value of all outstanding contracts. But many players in the market hold offsetting positions. So if, in theory, every entity that owns CDS had to settle its contracts tomorrow and "netted" all its positions against each other, a much smaller amount of money would change hands. But even a tiny fraction of that $54.6 trillion would still be a daunting sum.

The credit freeze and then the Bear disaster explain the drop in outstanding CDS contracts during the first half of the year - and the market has only worsened since. CDS contracts on widely held debt, such as General Motors' (GM, Fortune 500), continue to be actively bought and sold. But traders say almost no new contracts are being written on any but the most liquid debt issues right now, in part because nobody wants to put money at risk and because nobody knows what Washington will do and how that will affect the market. ("There's nothing to do but watch Bernanke on TV," one trader told Fortune during the week when the Fed chairman was going before Congress to push the mortgage bailout.) So, after nearly a decade of exponential growth, the CDS market is poised for its first sustained contraction.

***

ONE REASON THE MARKET TOOK OFF is that you don't have to own a bond to buy a CDS on it - anyone can place a bet on whether a bond will fail. Indeed the majority of CDS now consists of bets on other people's debt. That's why it's possible for the market to be so big: The $54.6 trillion in CDS contracts completely dwarfs total corporate debt, which the Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association puts at $6.2 trillion, and the $10 trillion it counts in all forms of asset-backed debt. "It's sort of like I think you're a bad driver and you're going to crash your car," says Greenberger, formerly of the CFTC. "So I go to an insurance company and get collision insurance on your car because I think it'll crash and I'll collect on it." That's precisely what the biggest winners in the subprime debacle did. Hedge fund star John Paulson of Paulson & Co., for example, made $15 billion in 2007, largely by using CDS to bet that other investors' subprime mortgage bonds would default.

So what started out as a vehicle for hedging ended up giving investors a cheap, easy way to wager on almost any event in the credit markets. In effect, credit default swaps became the world's largest casino. As Christopher Whalen, a managing director of Institutional Risk Analytics, observes, "To be generous, you could call it an unregulated, uncapitalized insurance market. But really, you would call it a gaming contract."

There is at least one key difference between casino gambling and CDS trading: Gambling has strict government regulation. The federal government has long shied away from any oversight of CDS. The CFTC floated the idea of taking an oversight role in the late '90s, only to find itself opposed by Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and others. Then, in 2000, Congress, with the support of Greenspan and Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers, passed a bill prohibiting all federal and most state regulation of CDS and other derivatives. In a press release at the time, co-sponsor Senator Phil Gramm - most recently in the news when he stepped down as John McCain's campaign co-chair this summer after calling people who talk about a recession "whiners" - crowed that the new law "protects financial institutions from over-regulation ... and it guarantees that the United States will maintain its global dominance of financial markets." (The authors of the legislation were so bent on warding off regulation that they had the bill specify that it would "supersede and preempt the application of any state or local law that prohibits gaming ...") Not everyone was as sanguine as Gramm. In 2003 Warren Buffett famously called derivatives "financial weapons of mass destruction."

***

THERE'S ANOTHER BIG difference between trading CDS and casino gambling. When you put $10 on black 22, you're pretty sure the casino will pay off if you win. The CDS market offers no such assurance. One reason the market grew so quickly was that hedge funds poured in, sensing easy money. And not just big, well-established hedge funds but a lot of upstarts. So in some cases, giant financial institutions were counting on collecting money from institutions only slightly more solvent than your average minimart. The danger, of course, is that if a hedge fund suddenly has to pay off on a lot of CDS, it will simply go out of business. "People have been insuring risks that they can't insure," says Peter Schiff, the president of Euro Pacific Capital and author of Crash Proof, which predicted doom for Fannie and Freddie, among other things. "Let's say you're writing fire insurance policies, and every time you get the [premium], you spend it. You just assume that no houses are going to burn down. And all of a sudden there's a huge fire and they all burn down. What do you do? You just close up shop."

This is not an academic concern. Wachovia (WB, Fortune 500) and Citigroup (C, Fortune 500) are wrangling in court with a $50 million hedge fund located in the Channel Islands. The reason: A dispute over two $10 million credit default swaps covering some CDOs. The specifics of the spat aren't important. What's most revealing is that these massive banks put their faith in a Lilliputian fund (in an inaccessible jurisdiction) that was risking 40% of its capital for just two CDS. Can anyone imagine that Citi would, say, insure its headquarters building with a thinly capitalized, unregulated, offshore entity?

That's one element of what's known as "counterparty risk." Here's another: In many cases, you don't even know who has the other side of your bet. Parties to the contract can, and do, transfer their side of the contract to third parties. Investment firms assert that transfers are well documented (a claim that, like most in the world of CDS, is impossible to verify). But even if that's true, you're still left with the fact that a given company's risks are being dispersed in ways that they may not know about and can't control.

It doesn't help that CDS trading is a haphazard process. Most contracts are bought and sold over the phone or by instant message and settled manually. Settlement has been sloppy, confirms Jamie Cawley of IDX Capital, a firm that brokers trades between big banks. Pushed by New York Fed president Timothy Geithner, the players have been improving the process. But even as recently as a year ago, Cawley says, so many trades were sitting around unfulfilled that "there were $1 trillion worth of swaps that were unsettled among counterparties."

Trade settlement is not the only anachronistic aspect of CDS trading. Consider what will happen with CDS contracts relating to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The two were placed in conservatorship on Sept. 7. But the value of many contracts won't be determined till Oct. 6, when an auction will set a cash price for Fannie and Freddie bonds. We'll spare you the technical reasons, but suffice it to ask: Can you imagine any other major market that would need a month to resolve something like this?

***

WITH WASHINGTON SUDDENLY in a frenzy of outrage over the financial markets, debating everything from the shape and extent of the mortgage plan to what should be done about short-selling, the future for CDS is very blurry. "The market is here to stay," asserts Cawley. The question is simply: What sorts of changes are in store? As this article was going to press, SEC chairman Christopher Cox asked the Senate to allow his agency to begin regulating CDS - mostly, it should be said, to rein in short-selling. And the SEC separately announced that it was expanding its investigation of market manipulation, which initially targeted the short-sellers, to CDS investors.

Under other circumstances, Cox's request might have been met with polite silence. But the convulsions over the mortgage bailout are so dramatic that they are reminiscent of the moment, soon after the Enron scandal, when Congress drafted the Sarbanes-Oxley legislation. The desire to blame short-sellers may actually result in powers for Cox that, until very recently, he showed no signs of wanting. Should legislators wade into this issue, the measures most widely seen as necessary are straightforward: some form of centralized trading or clearing and some form of capital or reserve requirements. Meanwhile, New York State's insurance commissioner, Eric Dinallo, announced new regulations that would essentially treat sellers of some (but not all) CDS as insurance entities, thereby forcing them to set aside reserves and otherwise follow state insurance law - requirements that would probably drive many participants from the market. Whether CDS players will find a way to challenge the rules remains to be seen. (ISDA, the industry's trade group, has already gone on record in opposition to Cox's proposal.) If nothing else, the New York law may provide additional impetus for the feds to take action.

For now, the biggest impact could come from the Financial Accounting Standards Board. It is implementing a new rule in November that will require sellers of CDS and other credit derivatives to report detailed information, including their maximum payouts and reasons for entering the contracts, as well as assets that might allow them to offset any payouts. Anybody who has tried to parse CEO compensation in recent years knows that more disclosure doesn't guarantee clarity, but any increase in information in the CDS realm will be a benefit. Perhaps that would limit the baleful effect of CDS on (must we consider it?) the next disaster - or even help us prevent it.

Kan iemand mij zeggen hoe groot dat kaartenhuis is dat men heeft opgebouwd?

quote:"It's sort of like I think you're a bad driver and you're going to crash your car," says Greenberger, formerly of the CFTC. "So I go to an insurance company and get collision insurance on your car because I think it'll crash and I'll collect on it." That's precisely what the biggest winners in the subprime debacle did. Hedge fund star John Paulson of Paulson & Co., for example, made $15 billion in 2007, largely by using CDS to bet that other investors' subprime mortgage bonds would default.

quote:Dat is wel een goede samenvatting denk ik zo.You can guess how Wall Street cowboys responded to the opportunity to make deals that (1) can be struck in a minute, (2) require little or no cash upfront, and (3) can cover anything. Yee-haw! You can almost picture Slim Pickens in Dr. Strangelove climbing onto the H-bomb before it's released from the B-52. And indeed, the volume of CDS has exploded with nuclear force, nearly doubling every year since 2001 to reach a recent peak of $62 trillion at the end of 2007, before receding to $54.6 trillion as of June 30, according to ISDA.

En nu is de tegenprestatie vele malen hoger dan dat er sowieso geld is. Uiteindelijk zal het wel minder zijn omdat A met C een deal sluit waarbij C A geld geeft en van A dan geld zou krijgen als het fout gaat.

En B dan ook zo'n deal sluit met C. Je kan dus een heleboel tegen elkaar wegstrepen. Maar er blijft ook nog enorm veel over.

Het is gewoon gokken om groot geld en sommigen zijn er beter in dan anderen.

De bubble is wel aanwezig, maar meer in de zin van het feit dat niemand een overzicht heeft wie aan wie geld verschuldigd is als er een bedrijf falliet gaat. In de huidige markt is het enorm gevaarlijk om een dergelijke CDS aan te gaan en dat gebeurd gelukkig ook niet veel meer, maar er zijn er nog een heleboel die al afgesloten zijn. Nu er grote bedrijven falliet gaan is het de vraag of iedereen zijn CDO schulden kan gaan afbetalen en eerlijk gezegt denk ik niet dat dat het geval is. Dat zou betekenen dat de gevolgen van een eventueel falliesement van een bank gigantische onverwachte gevolgen kan hebben voor andere zwaargewichten en die kunnen op hun beurt weer in de problemen komen en zo een dominoeffect veroorzaken.

Het bovenstaande is een versimpelde verklaring, maar de vrees is volkomen terecht.

Ik werk op dit moment in Londen en ben verantwoordelijk voor de administratie, waardering en rapportage van speciaal opgezette bedrijven (SPV's; special purpose vehicles) die dergelijke financiele transacties bevatten.

Mocht je dus meer vragen hebben en diepgang wilt, laat het maar weten

En ja Lehamn bezat een boel derivaten wat nu als een fail-out nog afgeboekt moet worden.

De swaps waar het hier om gaat worden in sneltrein afgebouwd. Beleggingsbanken transformeren weer langzaam in Spaarbanken of in genationaliseerde instituten.

De grootste player in dit spel was no doubt AIG, want die gaf meestal de tegenprestatie weg (als het fout ging). Maar AIG heeft uitstel van executie en zal langzaam verdwijnen van het toneel.

De hele CDS markt valt op dit moment stil. Omdat er geen sprake meer is van een absolute waarborg. Het is nu nog slechts een papieren belofte.

Wie hebben die dingen gekocht..... zowat hele wereld... ook onze banken, pensioenfondsen zitten er diep in.

De echte pijn voelen we pas (veel) later....maar we gaan hem voelen (daar twijfel ik niet aan)

quote:Volgens mij blijft er in veel gevallen helemaal niks over, omdat partijen hun uitstaande schuld niet kunnen betalen, terwijl deze schulden wel als bezittingen op de balans van de eisende partij staan.Op dinsdag 30 september 2008 13:44 schreef Dagonet het volgende:

A zegt tegen B: ik geef jou x geld, als het fout gaat dan krijg ik van jou xxxxxxxx geld.

En nu is de tegenprestatie vele malen hoger dan dat er sowieso geld is. Uiteindelijk zal het wel minder zijn omdat A met C een deal sluit waarbij C A geld geeft en van A dan geld zou krijgen als het fout gaat.

En B dan ook zo'n deal sluit met C. Je kan dus een heleboel tegen elkaar wegstrepen. Maar er blijft ook nog enorm veel over.

Resultaat: enorme afschrijvingen en als het een beetje tegenzit; nog meer faillissementen. Een soort Domino D-Day, maar dan anders.

Deze maand stress-testen.

quote:Derivatives market faces biggest test

Published: September 30 2008 16:17 | Last updated: September 30 2008 22:38

The $54,000bn credit derivatives market faces its biggest test in October as billions of dollars worth of contracts on now-defaulted derivatives on Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, Lehman Brothers and Washington Mutual are settled.

Highlighting the opacity of this market, it is still not clear how many contracts have to be settled, and whether payouts on the defaulted contracts, which could reach billions of dollars, are concentrated with any particular institutions.

According to dealers, insurance companies and investors such as sovereign wealth funds, which are widely believed to have written large amounts of credit protection through credit default swaps on financial institutions, could have to pay out huge amounts.

“There is a lot at stake,” said an executive at one big dealer. “This is a crisis time, and if these auctions do not go well, or if the amounts investors and dealers have to pay is seen as not being fair, it could have further negative repercussions on the CDS market.”

The “auction season” starts on Thursday, when the International Swaps and Derivatives Association has scheduled an auction for Tembec, a Canadian forest products company.

”This is a tried and tested process that we expect to run as seamlessly for these larger scale events as it did for the last nine credit events ISDA helped settle smoothly,” said Robert Pickel, chief executive officer of the International Swaps and Derivatives Association.

This is followed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac auctions on October 6. Then, Lehman is settled on October 10, and Washington Mutual is scheduled for October 23.

Even though it is possible that some participants in the credit derivatives market will have to make large pay-outs, the flipside is there could also be big winners. For every loss in credit derivatives, there is a gain.

The amount of credit derivatives contracts outstanding that reference Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac alone are estimated to be up to $500bn. The default was triggered under the terms of derivatives contracts by the US government’s seizure of the mortgage groups, even though the underlying debt is strong after the explicit guarantee from the US government.

The CDS contract settlement could result in billions of dollars of losses for insurance companies and banks who offered credit insurance in recent months. The recovery value will be set by an auction process. Usually, the bond that is eligible for the auction that trades at the lowest price – the so-called cheapest-to-deliver – is the one that sets the overall recovery value for the credit derivatives.

In the Lehman case, numerous banks and investors have already made losses due to exposure to Lehman as a counterparty on numerous derivatives trades. The auctions next week are for credit derivatives which have Lehman as a reference entity. There are likely to be fewer contracts outstanding than for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac because Lehman was not included in many of the benchmark credit derivatives. However, exposure remains unclear, which is one concern that regulators now have about the credit derivatives market.

Lehman’s bonds have been trading between 15 and 19 cents on the dollar, meaning that investors who wrote protection on a Lehman default will have to pay out between 81 and 85 cents on the dollar, a relatively high payout.

The previous biggest default in credit derivatives was for Delphi, the US car parts maker that went bankrupt in 2005 and which had about $25bn of CDS.

quote:Op dinsdag 30 september 2008 14:04 schreef soylent het volgende:

TVp.

Zo raar is dit product dus niet, en het is ook best logisch dat deze markt zo groot is. Immers, iedereen die investering heeft (denk bvb ook aan pensioenfondsen), maakt gebruik van deze producten. In het algemeen is de debt market veel groter dan de equity market, ook al heeft deze minder exposure op bvb rtl Z.

quote:Waves of Credit Default Swaps Incoming

Have you wondered why the Treasury asked for a $700 Bn emergency package with the full force of the Fed behind them, and gave the Congress less than a week to deliver it?

Either these fellows have lost their nerve or the markets are riding to a fall, and it could be terrific.

We've been looking for some event, something that would have created such an extraordinary set of actions as we have seen in the past few days.

This just might be it. Special thanks to Yves Smith for flagging it.

Time to start settling those Credit Default Swaps for Fannie and Freddie (Oct. 6), Lehman Brothers (Oct. 10) and Lehman Brothers (Oct 23).

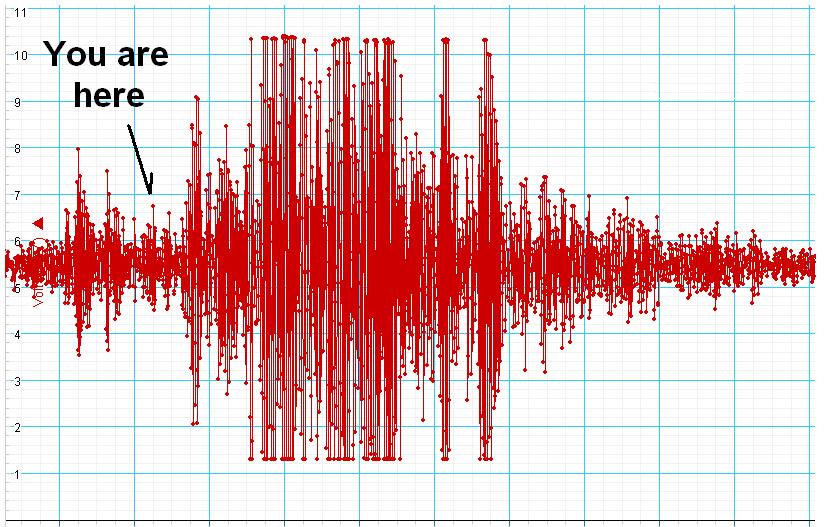

LIBOR is eight standard deviations from the norm, because the banks don't know who is holding what in their cards, but there might be some Aces and Eights in there. The TED spread is at an all time record high.

An insurance company is said to be heavily exposed.

Do you need to buy a vowel? Let's hope we get lucky.

Brace for impact.

quote:Wordt er bij een swap alleen betaald (geruild) na het verstrijken van de termijn van het contract of in geval van failure bij een credit swap?Op dinsdag 30 september 2008 13:41 schreef Dagonet het volgende:

[..]

[..]

Dat is wel een goede samenvatting denk ik zo.

quote:Het is mij nog even onduidelijk hoe dit in zijn werk gaat, er staat dat er een auction process bij te pas komt. Ik ging ervan uit dat een cds aldus werkte. A leent 1 miljoen dollar bij B. B wil zich indekken in geval A rente en aflossing niet kan betalen. Hij betaalt aan een verzekeraar 0,1 miljoen dollar, die in geval van failure van A daarvoor 1 miljoen dollar betaalt aan B. B krijgt dus altijd 0,9 miljoen netto terug.Op vrijdag 3 oktober 2008 13:16 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

Kick....

Deze maand stress-testen.

[..]

Waarom komt er nu ineens een auction bij te pas? Of worden op die auction beide poten van de transactie pas geregeld?

quote:Kan van alles zijn.... het is een afgeleid product.Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:15 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

[..]

Wordt er bij een swap alleen betaald (geruild) na het verstrijken van de termijn van het contract of in geval van failure bij een credit swap?

Een soort Lloyds van Londen (waar je van alles en nog wat kunt verzekeren), maar dan als verkoopproduct voor de financiële instellingen. AIG zit er in ieder geval heel diep in.

En reken maar dat een boel 'slimme beleggers' hun producten een beetje fatsoenlijk afgeschermd hebben.

En deze maand is het pay-day. 3 van de 'big' five bestaan niet meer.

quote:Ik vermoed idd zoiets... dit is voor mij onbekend terrein.Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:30 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

Waarom komt er nu ineens een auction bij te pas? Of worden op die auction beide poten van de transactie pas geregeld?

quote:Wat ik begrepen heb is, dat de swaps vooral gebruikt worden om renteschommelingen op te vangen. Maar in deze gevallen zal het idd gaan om subprime loans, schat ik in, of paketten daarvan. Die dus bij een verzekeraar zijn geswapt door in dit geval Lehmans bijv. In principe is deze setting dus gunstig voor Lehmans.Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:32 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

Kan van alles zijn.... het is een afgeleid product.Omvallen van een bedrijf. Wanbetaler zo zot wat je verder nog kunt bedenken.

Maar wrs heeft Lehmans ook gefungeerd als verzekeraar bij andere swaps?

[ Bericht 3% gewijzigd door Ryan3 op 05-10-2008 00:47:31 ]

quote:Hangt er een beetje vanaf wat in de prospectus staatOp zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:40 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

[..]

Wat ik begrepen heb is, dat de swaps vooral gebruikt worden om renteschommelingen op te vangen. Maar in deze gevallen zal het idd gaan om subprime loans, schat ik in, of paketten daarvan. Die dus bij een verzekeraar zijn geswapt door in dit geval Lehmans bijv. In principe is deze setting dus gunstig voor Lehmans.

We zullen het wellicht maandag weten ...ik verwacht toch wel een beetje sensatie deze maand.

Boze tongen gaan zelfs zover dat de bail-out ervoor bedoeld is om buitenlandse investeerders te beschermen (d.m.v. het oppoetsen van de verzekeringsbalans)

quote:Die laatste moet je even uitleggen, die begrijp ik niet.Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:48 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

Hangt er een beetje vanaf wat in de prospectus staat

We zullen het wellicht maandag weten ...ik verwacht toch wel een beetje sensatie deze maand.

Boze tongen gaan zelfs zover dat de bail-out ervoor bedoeld is om buitenlandse investeerders te beschermen (d.m.v. het oppoetsen van de verzekeringsbalans)

We weten gewoon niet wat er op de balans staat van pensioenfondsen die in de VS hebben geïnvesteerd hè.

quote:AIG Bail-out van 85 miljardOp zondag 5 oktober 2008 00:54 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

[..]

Die laatste moet je even uitleggen, die begrijp ik niet.

We weten gewoon niet wat er op de balans staat van pensioenfondsen die in de VS hebben geïnvesteerd hè.

En wordt beweerd dat de nieuwe bail-out van 750 miljard (FED spaarpotje) ook een beetje bedoeld is om AIG te helpen.

quote:Ah, op die manier.Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 01:03 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

AIG Bail-out van 85 miljard

En wordt beweerd dat de nieuwe bail-out van 750 miljard (FED spaarpotje) ook een beetje bedoeld is om AIG te helpen.

Hier staat de kern van het probleem trouwens:

quote:AIG decided to get into this market a few years ago, and quickly became one of the biggest players. But they didn’t fully understand the risks associated with this market, and looked at it the same way they looked at homeowners insurance; figuring that they just needed to sell a lot of insurance policies so that a loss of one home would be made up by the premiums earned on all of the other homes. But a fire at one home typically doesn’t spread to all other homes, while a default by one bond issuer quickly turns into problems for other bond issuers.

Total derivatives (notional amount): $96.2 trillion (September, 2005)

Interest rate contracts: $82.0 trillion

Foreign exchange contracts: $8.6 trillion

Total number of commercial banks holding derivatives: 769

Is relatief 'oud' (11 april 2008), maar zeer relevant.

Paar quotes:

quote:Credit default swaps are the most widely traded form of credit derivative. They are bets between two parties on whether or not a company will default on its bonds. In a typical default swap, the “protection buyer” gets a large payoff if the company defaults within a certain period of time, while the “protection seller” collects periodic payments for assuming the risk of default.

[...]

A Parade of Bailout Schemes

Now that some highly leveraged banks and hedge funds have had to lay their cards on the table and expose their worthless hands, these avid free marketers are crying out for government intervention to save them from monumental losses, while preserving the monumental gains raked in when their bluff was still good. In response to their pleas, the men behind the curtain have scrambled to devise various bailout schemes; but the schemes have been bandaids at best. To bail out a $681 trillion derivative scheme with taxpayer money is obviously impossible. As Michael Panzer observed on SeekingAlpha.com:

As the slow-motion train wreck in our financial system continues to unfold, there are going to be plenty of ill-conceived rescue attempts and dubious turnaround plans, as well as propagandizing, dissembling and scheming by banks, regulators and politicians. This is all happening in an effort to try and buy time or to figure out how the losses can be dumped onto the lap of some patsy (e.g., the taxpayer).

[...]

The banks will therefore no doubt be looking for one bailout after another from the only pocket deeper than their own, the U.S. government's. But if the federal government acquiesces, it too could be dragged into the voracious debt cyclone of the mortgage mess. The federal government's triple A rating is already in jeopardy, due to its gargantuan $9 trillion debt. Before the government agrees to bail out the banks, it should insist on some adequate quid pro quo. In England, the government agreed to bail out bankrupt mortgage bank Northern Rock, but only in return for the bank's stock. On March 31, 2008, The London Daily Telegraph reported that Federal Reserve strategists were eyeing the nationalizations that saved Norway, Sweden and Finland from a banking crisis from 1991 to 1993. In Norway, according to one Norwegian adviser, “The law was amended so that we could take 100 percent control of any bank where its equity had fallen below zero.”6 If their assets were “marked to market,” some major Wall Street banks could already be in that category.

Even snel gerekend betekent dit dat er grofweg 24 tot 48 miljard moet worden opgehoest door de verkopers van CDS-contracten. Hier kunnen best wel eens wat kleine hedge-funds tussen zitten die niet aan de verplichtingen kunnen voldoen. Daarmee komen er alsnog miljarden aan afschrijving bij grote namen in de bankwereld terecht.

http://www.reuters.com/ar(...)dUSN0639328620081006

quote:Een belangrijk grote onzekere factor die vandaag het toch al dramatische sentiment verder kan beroeren is de afwikkeling van de portefeuille van zogenaamde credit default swaps ter waarde van $ 400 miljard van de vorige maand failliete zakenbank Lehman Brothers. Een Credit Default Swap is een overeenkomst tussen twee partijen waarbij het kredietrisico van een derde partij wordt overgedragen. Meerdere grotere marktspelers zoals Morgan Stanley en Goldman Sachs maar ook anderen zijn blootgesteld aan deze Lehman portefeuille. Niemand weet hoe de afwikkeling van deze Lehman CDS portefeuille zal uitpakken. Velen zijn extreem zenuwachtig hiervoor!

quote:Ongelovelijk, WAT een bedragen. Daar kun je je gewoon helemaal niks bij voorstellen.Op zondag 5 oktober 2008 01:23 schreef Ryan3 het volgende:

In de derivatenhandel gaan sws onvoorstelbare bedragen om hè (van wikipedia, cijfers uit 2005):

Total derivatives (notional amount): $96.2 trillion (September, 2005)

Interest rate contracts: $82.0 trillion

Foreign exchange contracts: $8.6 trillion

Total number of commercial banks holding derivatives: 769

Wat ik mij afvraag, he: hoeveel geld is er wereldwijd in totaal eigenlijk in omloop (dus alle verschillende valuta van alle landen die er zijn)? Uitgedrukt in dollars en euro's?

quote:Er is veel meer fictief geld dan dat er echt geld in de omloop is.Op vrijdag 10 oktober 2008 19:16 schreef StateOfMind het volgende:

[..]

Ongelovelijk, WAT een bedragen. Daar kun je je gewoon helemaal niks bij voorstellen.

Wat ik mij afvraag, he: hoeveel geld is er wereldwijd in totaal eigenlijk in omloop (dus alle verschillende valuta van alle landen die er zijn)? Uitgedrukt in dollars en euro's?

322 miljard, hmmm.. Waarom komt dit nauwelijks in de media? Onwetenheid of zal het allemaal wel mee vallen?

quote:Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 19:10 schreef HassieBassie het volgende:

Nu de eerste golf derivaten op Lehman Brothers is afgetikt op 322 Miljard dollar, is het wachten tot 21 oktober om te kijken wie dit moet gaan betalen. Het maakt eigenlijk niet zoveel uit wie dit moet gaan betalen, eigenaars van dit stukje puin zijn sowieso de lul.

322 miljard, hmmm.. Waarom komt dit nauwelijks in de media? Onwetenheid of zal het allemaal wel mee vallen?

quote:Daar heb ik net een docu over gekeken (Money as Debt). Maar zoals hierboven al gezegd, er is véél meer fictief geld dan dat er werkelijk bestaat. Een korte situatiebeschrijving (als ik het hele verhaal goed begrepen heb!):Op vrijdag 10 oktober 2008 19:16 schreef StateOfMind het volgende:

[..]

Ongelovelijk, WAT een bedragen. Daar kun je je gewoon helemaal niks bij voorstellen.

Wat ik mij afvraag, he: hoeveel geld is er wereldwijd in totaal eigenlijk in omloop (dus alle verschillende valuta van alle landen die er zijn)? Uitgedrukt in dollars en euro's?

"Veel mensen denken dat banken geld uitlenen wat bij hen gestort is. Makkelijk om je voor te stellen maar dit is niet de waarheid. Banken creeren het geld wat zij uitlenen. Niet uit het geld wat zij verdiend hebben, niet uit gestort geld, enkel van de belofte van de lener om het geld terug te betalen."

Stel je voor: Er komt een nieuwe bank, deze heeft op het begin geen houders. Maar investeerders hebben een reservestorting gedaan van $1111,12. De vereiste reserveratio is 9 fictieve dollars tegenover 1 bestaande dollar. Dus deze bank mag 9 maal de $1111,12 uitlenen

9 * $1111,12 = $10.000,08

De lener gebruikt deze net geleende $10.000,- om een auto te kopen. De verkoopster van de auto stort dit geld op de bank. Dit geld mag door de bank niet vermenigvuldigd worden. Het mag met een 9:1 verhouding weer gebruikt worden. Met andere woorden; de bank heeft nu beschikking tot een extra $9.000,- . Waarna dit proces zich herhaalt tot $8.100,- etc.Wanneer dit proces zich 90x voltrekt heb je ca. $100.000,- aan fictief geld, op een begininvestering van slechts $1111,12

"Echter is de 9:1 verhouding niet overal het geval. Er zijn voor sommige typen rekeningen zijn 20:1 en 30:1 gebruikelijk. En recentelijk, door het gebruik maken van dossierkosten. Om de vereiste reserve te krijgen van de lener hebben banken een manier gevonden om de verhoudingen totaal te omzeilen"

wat gebeurt er dan met de geld dat wij ze geven?

quote:'wij' als spaarders, of 'wij' als de bevolking die een lening afsluit?Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 19:46 schreef TubewayDigital het volgende:

@ tomm90

wat gebeurt er dan met de geld dat wij ze geven?

Nothing to see here, just move along people

quote:wij als spaardersOp maandag 13 oktober 2008 19:57 schreef Tomm90 het volgende:

[..]

'wij' als spaarders, of 'wij' als de bevolking die een lening afsluit?

quote:Oh sorry, ik las het verkeerd, Je bedoelt spaarders met het 'gegeven' geld door ons?Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 19:46 schreef TubewayDigital het volgende:

@ tomm90

wat gebeurt er dan met de geld dat wij ze geven?

De boekhouding van een bank moet laten zien dat voor elke $9,- aan uitgeleend geld, zij $10,- moeten bezitten aan gestort geld. Als je het hele verhaal duidelijk wil hebben is het aan te raden een keer naar de docu kijken. Na bepaalde delen al meer dan 1 keer bekeken te hebben zijn een aantal dingen me zelf ook nog niet duidelijk

quote:Ok, 200 miljard Pond. Wie gaat dat ophoesten? Iemand?A fresh wave of fear hit banks yesterday as traders tried to settle hundreds of billions of pounds of complex products in a move that could leave some with heavy losses.

By Katherine Griffiths, Financial Services Editor

Last Updated: 11:24PM BST 10 Oct 2008

An auction to settle insurance liabilities over the collapse of Lehman Brothers has caused fresh anxiety

A sale of complex products relating to Lehman Brothers caused new anxiety Photo: REUTERS

The cause of the anxiety was an auction to settle insurance liabilities over the collapse of Lehman Brothers.

Investors who have bought the insurance, known as credit default swaps, are trying to get those who provided the insurance to pay up.

Yesterday the parties were attempting to agree how much would be paid.

There was fear in the City and on Wall Street that some parties would not be able to settle the contracts. This could have a domino effect through the financial system, leading to a string of defaults. Analysts and investors said the main problem was that it was not clear where the problems would end. The bill could total about £233 billion, according to one leading banking analyst.

Preliminary results from the auction indicated that about 90 per cent of the debts will be paid leaving other financial institutions with a bill of around £200 billion.

Potential defaults may not be known for days, as the deadline for payments is Oct 21.

The lack of clarity led to a renewed sell-off of shares and exacerbated the deep freeze in the credit markets, as banks are reluctant to lend to each other when they do not know if the debt will be repaid.

A senior financier who is helping the Government hammer out its £500 billion bail-out plan with the British banks said: "The problem with credit default swaps is people do not understand the links between the different counterparties. It is like dripping poison in the Danube and it turning up days later in the Amazon."

The Treasury unveiled a package of bold measures this week to try to stop the crisis in the banking sector and restore market liquidity. Lending among banks and from large money funds must be restored to get the world's financial system on track.

The signs yesterday were not encouraging, as the price of insuring the debt of several companies, including Morgan Stanley, rose. The concern over Morgan Stanley came after the credit ratings agency Moody's issued a warning about its long-term debt.

quote:Er zijn naar mijn inschatting nog maar verdomd weinig partijen over dir uberhaupt nog geld los hebben zitten, laat staan 300 miljard dollar.. Om maar te zwijgen over de bedrijven die de swaps als bezittingen op de balans hebben staan.Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 20:44 schreef Tweeke het volgende:

Wie dat gaan ophoesten? De verkopers van de Credit Default Swap contracten. Maar dat had je ongetwijfeld ook al uit het gequote artikel gehaald. Of ze het kunnen betalen is maar de vraag (vooral wanneer kleine hedgefunds de contracten hebben verkocht). Als de verkoper niet kan betalen dan komt de schuld toch bij de koper van de default-bescherming terecht. Hoewel dat vaak grote en 'solide' partijen zijn, zouden daar nog wel eens harde klappen kunnen vallen.

Wat gebeurt er als niemand de schulden op zich kan nemen?

quote:Derivaten transacties lopen vrijwel altijd via een clearing. Ook de OTC transacties.Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 20:44 schreef Tweeke het volgende:

Wie dat gaan ophoesten? De verkopers van de Credit Default Swap contracten. Maar dat had je ongetwijfeld ook al uit het gequote artikel gehaald. Of ze het kunnen betalen is maar de vraag (vooral wanneer kleine hedgefunds de contracten hebben verkocht). Als de verkoper niet kan betalen dan komt de schuld toch bij de koper van de default-bescherming terecht. Hoewel dat vaak grote en 'solide' partijen zijn, zouden daar nog wel eens harde klappen kunnen vallen.

Het is gewoon een extra instrument om te hedgen. Juich het toe, schrijf het niet af omdat je het niet begrijpt. Het is ook totaal geen gokken. Met een CDS kun je het default risk hedgen en dat zorgt voor meer liquiditeit.

Het bedrag lijkt me ook schromelijk overdreven. Er zullen veel tegenovergestelde trades bij zitten (net als bij swaps en futures). Netto staat er dus veel minder uit.

quote:Klinkt ehm, vrij onbegrijpelijk voor mij helaas. Het default risk hedgen? Das vast geen Nederlands. Maar goed, als je bedoelt wat ik denk dat je bedoelt, is het dan niet pijnlijk als bedrijven waarop de swaps zijn aangegaan omvallen? Iemand moet dan toch gaan betalen?Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 20:55 schreef Shakes het volgende:

[..]

Derivaten transacties lopen vrijwel altijd via een clearing. Ook de OTC transacties.

Het is gewoon een extra instrument om te hedgen. Juich het toe, schrijf het niet af omdat je het niet begrijpt. Het is ook totaal geen gokken. Met een CDS kun je het default risk hedgen en dat zorgt voor meer liquiditeit.

Het bedrag lijkt me ook schromelijk overdreven. Er zullen veel tegenovergestelde trades bij zitten (net als bij swaps en futures). Netto staat er dus veel minder uit.

quote:(Heel simpel en niet direct een praktijk voorbeeld: Slechts ter illustratie)Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 21:05 schreef HassieBassie het volgende:

[..]

Klinkt ehm, vrij onbegrijpelijk voor mij helaas. Het default risk hedgen? Das vast geen Nederlands. Maar goed, als je bedoelt wat ik denk dat je bedoelt, is het dan niet pijnlijk als bedrijven waarop de swaps zijn aangegaan omvallen? Iemand moet dan toch gaan betalen?

Je koopt een product van Bedrijf A. Dat bedrijf belooft je een bepaalde waarde in jaar x. In feite heb je dus geld uitstaan bij het bedrijf en tot x loop je het risico dat het bedrijf 'default'; oftewel niet meer aan zijn verplichtingen kan voldoen. Dus je die waarde in jaar x niet meer kan betalen. Dat is het default risk. Dat risico kun je dus verkleinen/ teniet doen door middel van een CDS.

Dus je koopt een CDS dat uitbetaald als dat bedrijf failliet gaat. Dus als het bedrijf default (niet aan zijn verplichtingen kan voldoen) dan levert de CDS geld op. Dus door middel van een CDS wordt je risico kleiner.

Wie verkoopt een CDS en waarom? Dat kunnen verzekeraars zijn (bijvoorbeeld AIG) maar ook market makers (net als bij opties waar je trade met market makers). Zij krijgen de premie, de premie wordt bepaald door middel van modellen. Ze zullen bijvoorbeeld heel veel CDS contracten verkocht hebben en door correlatie, credit rating en dergelijke zullen ze geld verdienen (tenminste: volgens het model). Dus men gaat er al vanuit dat men moet uitbetalen. Dat kan men aan tot een bepaald bedrag, maar de kans is waarschijnlijk dat er een clearing tussenzit. Die doet ook risico management op de positie dus als een verkoper van CDS contracten al teveel defaults heeft gehad zal hij waarschijnlijk al zijn posities af moeten wikkelen en zijn verlies nemen.

Hopelijk ben ik een beetje duidelijk.

quote:Omdat het geld feitelijk niet bestaat, maar toch is het er. Wanneer er een 'bank run' zou komen waarbij een groot deel vd bevolking hun spaargeld wil opnemen is dit onmogelijk en stort het totale systeem in.Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 20:59 schreef TubewayDigital het volgende:

ik heb die docu (47 min) gezien. Wat betreft het uitlenen van geld dat er niet is? Dat zou toch niet erg hoeven zijn als je er waarde mee creeert?

quote:het geld wordt gecreerd uti het niets maar er wordt ook gewerkt/geproduceerd dus het gecreeerde geld wordt gedekt door productie in de reeele wereldOp maandag 13 oktober 2008 22:27 schreef Tomm90 het volgende:

[..]

Omdat het geld feitelijk niet bestaat, maar toch is het er. Wanneer er een 'bank run' zou komen waarbij een groot deel vd bevolking hun spaargeld wil opnemen is dit onmogelijk en stort het totale systeem in.

quote:Insurance on Lehman Debt Is the Industry’s Next Test

Nearly three weeks after the Wall Street bank sank into bankruptcy, financial companies and investment funds that wrote what are effectively insurance policies on Lehman Brothers’ debts are being called on to pay hundreds of billions of dollars in claims.

Whether those claims can or will be paid, and the financial repercussions that could follow if they are not, will signify the biggest test yet for the vast, unregulated market in credit-default swaps.

The danger is that the claims on the Lehman default are so large — they are estimated at $400 billion to $600 billion — that settling them could leave some companies with large, perhaps even crippling, losses and heighten the turmoil in the financial markets.

quote:Derivatives: The Great Unwind

.

Another guest post from MG who went from Wharton to Wall St. to real estate to Blown Mortgage.

The market was up strong yesterday. Other than the shares of bank stocks, you have to wonder why. The worldwide central bank bailout is not intended for the equity investor, or general public, or business, or you, or me. It’s intended for banks, ostensibly to spur lending, but more likely to keep them afloat through next week’s Great Derivatives Unwind. This has got to be a big part of the motivation of the CBs to provide unlimited lending to banks.

Distracted by worldwide stock market crashes, attention shifted away from Lehman’s derivatives’ payouts scheduled for October 21. Recovery value has been set at 8.625 cents per $1.00, which means that sellers of credit protection must pay 91.375 cents to the buyers (according to Creditex, the company that holds auctions).

More than 350 banks and investors signed up to settle credit-default swaps tied to Lehman. The list of participants in the auction includes Newport Beach, California-based Pacific Investment Management Co. PIMCO, manager of the world’s largest bond fund, Chicago-based hedge fund manager Citadel Investment Group LLC and AIG, the New York-based insurer taken over by the government, according to the International Swaps and Derivatives Association in New York.

According to JPMorgan, the largest foreign bank holders of Lehman’s derivatives are Deutsche Bank, Barclays, Societe Generale, UBS, Credit Suisse and Credit Agricole. Overall, as of June 30, 2008, the top ten US banks in terms of derivatives exposure were: JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citibank, Wachovia, HSBC USA, Wells Fargo, Bank of New York, State Street Bank, SunTrust Bank, and PNC Bank, according to the Comptroller of the Currency Administrator of National Banks’ Quarterly Report on Bank Trading and Derivatives Activities for the second quarter of 2008. Lots of other good information too, if you like this sort of thing, as I do.

And this is just the beginning. Few losses are expected from the failed GSEs. Fannie Mae’s senior debt settled at 91.51 and subordinated debt at 99.9 cents on the dollar; Freddie Mac senior debt was 94.00 and subordinated debt was 98 cents on the dollar. Washington Mutual could be another story. It’s Credit Event Auction will settle, meaning prices will be determined, on October 23. Just last week there were credit events at the largest three Iceland banks, all of which have large quantities of derivatives outstanding. These are all financial institutions; industrials haven’t started yet.

Nonetheless, the market’s up. For technical types, Mish Shedlock has a good and almost-understandable-by-laymen explanation of where the market is in terms of Elliott Wave theory. He says, “In terms of price, given the magnitude of today’s move on top of the huge move up from Friday’s low, the rally may be 65% over already. In terms of time, the rally likely has several weeks to a couple of months to play out.” See S&P 500 Crash Count at www.globaleconomictrendanalysis.com

In my opinion, the markets are still very fragile. Charts or no charts, it wouldn’t take much to see another cliff dive. We’ll see what happens next.

Big tab for Lehman swap sellers

Investors who bet Lehman Brothers wouldn’t default on its debt are, unsurprisingly, looking at a hefty bill. Sellers of credit default protection on the bankrupt New York brokerage firm will have to pay 91.38 cents on the dollar later this month to settle with the buyers of Lehman credit default swaps. The price was set in an auction Friday whose results were posted on Creditfixings.com.

The Lehman price fixing is below the level implied by bond market trading. Lehman bonds recently fetched 13 cents on the dollar, Bloomberg reports. The auction is being closely watched because it offers a test of an unregulated marketplace that grew at a rapid clip for years before the credit bubble burst last year. Still, it’s not completely clear what the final settlement of the Lehman trades, due in two weeks, will mean for the rest of us.

The financial crisis has put a spotlight on the obscure world of credit default swaps - which trade in a vast, unregulated market that most people haven’t heard of and even fewer understand. Fortune recently wrote about the threat of credit default swaps, noting these privately traded derivatives contracts have ballooned from nothing into a $54.6 trillion market in just over a decade.

TheDeal.com reported Thursday that uncertainty tied to the Lehman credit default swaps was responsible for some of the fear that swept through the markets this week, as banks hoard cash to make sure they have enough to settle CDS trades. But Bloomberg notes that some observers are skeptical. “Fears surrounding the Lehman auction settlement are overblown,” Bank of America credit strategist Jeffrey Rosenberg wrote in a note to investors. “The economic impact of the Lehman bankruptcy through CDS contracts has for the most part already occurred.”

http://dailybriefing.blog(...)lehman-swap-sellers/

quote:In zekere zin is dat ook.... niemand had een paar jaar geleden kunnen voorspelen dat banken (in relatieve economische voorspoed) wel eens failliet kunnen gaan. En toch gebeurd het...Op woensdag 15 oktober 2008 00:27 schreef beantherio het volgende:

Een echte kenner ben ik niet, maar ik vind het eigenlijk idioot dat er zoiets bestaat als een CDS. Vooral als het gaat om grotere bedrijven als Lehman dan lijkt het haast het Russisch roulette onder de verzekeringsproducten.

Banken hebben risico's genomen die behoorlijk over the top gaan. Banken anno 2008 lijken in de verre verste niet op banken van voor 1990. Just another accident waiting to happen.

quote:Banken en pensioenfondsen ook, maar daar hoor je nu nog weinig over, kochten obligaties met een rating beter of gelijk b.v. AA, om het risico laag te houden. Om een mindere obligatie die rating te laten krijgen pakte de verkoper v/d obligatie er soms een CDS bij in, zodat de rating v/h pakketje hoger werd.Op woensdag 15 oktober 2008 00:54 schreef Drugshond het volgende:

[..]

In zekere zin is dat ook.... niemand had een paar jaar geleden kunnen voorspelen dat banken (in relatieve economische voorspoed) wel eens failliet kunnen gaan. En toch gebeurd het...

Banken hebben risico's genomen die behoorlijk over the top gaan. Banken anno 2008 lijken in de verre verste niet op banken van voor 1990. Just another accident waiting to happen.

Omdat er nu op veel grotere schaal dan 'verwacht' gebruik gemaakt wordt van de CDS verzekeringen (called to perform) vallen de verzekeraars die de CDSs verkochten om, zoals laatst AIG die door de overheid gered werd - voorlopig.

Als de verzekeraar omvalt is de verzekering er ook niet meer en heeft het pakketje (obligatie + CDS) een lagere rating, m.a.w. kans op niet betalen groter. Dus het leek een klein risico, maar wordt bij omvallen v/d risico verzekeraar een groot risico.

Het is gewoonweg dom van de kopers als ze alleen naar de rating gekeken hebben en niet naar de hypotheken die eraan ten grondslag lagen. Maar goed, greed was good.

quote:Denk dat AEGON de 200 miljard gaat opzuigen, in ruil voor veel verwaterde aandelenOp zaterdag 4 oktober 2008 08:27 schreef Ericr het volgende:

Aegon de volgende nationalisatie dus of zal Bos geen boodschap hebben aan een omvallend verzekeringsbedrijf?

quote:Nou het is wel handig als je subprime loans verstrekt om een swap aan te gaan met een derde partij natuurlijk. Aanvankelijk echter werden, wat ik begrepen heb, swaps vooral gebruikt om rente op geleend geld te stabiliseren.Op woensdag 15 oktober 2008 00:27 schreef beantherio het volgende:

Een echte kenner ben ik niet, maar ik vind het eigenlijk idioot dat er zoiets bestaat als een CDS. Vooral als het gaat om grotere bedrijven als Lehman dan lijkt het haast het Russisch roulette onder de verzekeringsproducten.

Degenen die een credit default swap aangaat als derde partij is natuurlijk wel een gokker. Wat ik begrepen heb is dat de hypotheekleningen derhalve in pakketten werden gebundeld met een rating van AAA tot BBB (zogenaamde traunches), zo werden doorverkocht en zo ook werden geswapt.

quote:De verhouding is wel gewoon 9:1, dus van elke $10 dollar aan gestort geld kan een bank $90 dollar uitlenen. Maarja, als de persoon van die initiele storting zijn centen terug wil kan dat niet omdat de bank dan geen reserve van 10% meer heeft. In de praktijk lenen ze minder uit dan die 900%, om zichzelf en andere banken niet in de problemen te brengen. Ze gaan dan bijvoorbeeld uit van 90%. Dit zorgt dan voor een balans van bijv. $100 gestort geld, $90 uitgeleend geld en $10 als reserve. Maar die $90 komt weer bij een andere bank terecht, waarvan weer $81 mag worden uitgeleend etc.Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 20:04 schreef Tomm90 het volgende:

De boekhouding van een bank moet laten zien dat voor elke $9,- aan uitgeleend geld, zij $10,- moeten bezitten aan gestort geld. Als je het hele verhaal duidelijk wil hebben is het aan te raden een keer naar de docu kijken. Na bepaalde delen al meer dan 1 keer bekeken te hebben zijn een aantal dingen me zelf ook nog niet duidelijk

Dit proces van cumulatieve geldcreering zorgt er uiteindelijk dus voor dat nieuw geld (van de Centrale Bank) goed is voor, in dit geval, 9 keer dat bedrag aan fictief geld. (Zo begrijp ik het althans, aan de hand van Wikipedia)

In Money as Debt doet de eerste bank wel zo'n mega lening en komen ze van die $1111, tot wel $100.000. In theorie zou elke bank zulke mega leningen kunnen doen en kom je tot een veel hoger bedrag. Maar in de praktijk doet dus niemand dit.

quote:Markets hold breath as $360bn Lehman swaps unwind

The $54trillion credit derivatives market faces a delicate test as $360bn worth of contracts on now-defaulted derivatives on Lehman Brothers are due to be settled on Tuesday.

By Louise Armitstead and Peter Koenig

Last Updated: 7:47PM BST 18 Oct 2008

Lehman Brothers' complex network of derivatives will be settled on Tuesday October 22

Lehman Brothers' complex network of derivatives will be settled on Tuesday October 22

Due to the opacity of the market, which is one of the most complex, least regulated and least understood in the global financial system, it is still not clear how many contracts have to be settled or which institutions will take the ultimate hits once the billions of dollars worth of contracts have been unravelled. The collapse of Lehman Brothers, is expected to trigger credit default swap (CDS) protection pay-outs of about $400bn but because the contracts were sold many times through different counterparties it is not yet known who will be liable.

One commentator said: “This will be the greatest illustration of the follies of Wall Street and how unnecessarily complicated the wild off-track betting became in the past few years.”

Five years ago Warren Buffett, the iconic American investor, warned that the chaotic profusion of derivatives used by companies and hedge funds to fund financial growth were “financial weapons of mass destruction.’’

Bankers in the City and on Wall Street are bracing for yet another round of turbulence as the contracts are unwound.

The Bank of England and the Federal Reserve in America have said they will keep their special liquidity windows open late on Tuesday night to allow the contracts to settle.

“We’re in unchartered waters here and it may all prove an anti-climax,” said a senior City banker on Friday, “but everyone will be watching the situation and wondering what’s going to happen.”

An earlier auction of Lehman-related derivatives on October 10 prompted early fears that banks and investors could lose $400 billion. In the event, the discounts on the Lehman-related paper that day realised losses of only $6 billion.

At the core of Tuesday’s cash exchange between banks stands a quasi-insurance product, the credit default swaps. Investors buy CDS’s to protect themselves against the possibility of default on securities issues by firms such as Lehman. During the boom years, banks’ insurers and hedge funds created and sold CDS’s to raise what appeared to be risk-free cash in the form of premium payments.

On September 16, Lehman filed for bankruptcy, leaving them obliged to payout on CDS’s written to protect investors against the possibility of a default on Lehman paper.

City bankers say that Lehman also holds a portfolio of CDS’s written to protect against other institutions defaulting and these, too, could get caught up in Tuesday’s action.

“This will arguably be the biggest cash-exchange day and somebody will fail,” one analyst warned last week.

Nou ja: als Lehman is afgewikkeld en daar geen al te grote slachtoffers uit voortkomen dan is het CDS-fenomeen op de wat kortere termijn geen echt probleem meer denk ik. Correctie: hoop ik.

quote:Ja......Op maandag 20 oktober 2008 20:20 schreef beantherio het volgende:

Wat ik me trouwens nog afvroeg: zijn die CDS-contracten op een vergelijkbare, onderdoorzichtige manier verpakt en doorverkocht als al die rotte sub prime hypotheken? Met andere woorden: krijgen we de situatie dat onwetende banken of financials hier in Europa morgen opeens een mannetje voor de deur hebben staan met de vraag "mag ik effe 10 miljard van u vangen?".

quote:Reggie heeft een schatting gemaakt waar de verliezen zitten.... flink lijstjeFirst, if the claims are correct: Then the entire CDS game is one gigantic high-finance version of "pick pocket."

That is, you come to me for a CDS on Lehman. I charge you $100,000. Then I immediately go find someone who will sell me the same contract for $90,000. I have now "picked your pocket" to the tune of $10,000, and (theoretically anyway) I have no risk. This continues until the last sucker says "no mas!" on a cheaper price, at which point that particular chain of CDS come to a close, until the next buyer shows up.

If this is the essence of the CDS game then the entire scheme and the dealers' insistence on keeping these things off a public exchange is an artifice with intent to defraud. Why? Because by keeping bid/ask and O/I hidden these banks are able to continue to play this game of "steal from the guy you sell to by obscuring the price"; indeed, that is the essence of the trade! This market doesn't exist to make a market or to set a price for risk, it instead serves as nothing other than a high-finance looting operation with everyone putting in the maximum effort to obscure market facts so as to be able to maximally exploit the customer!

Why do I make this charge? Because there were allegedly $600 billion worth of contracts written on Lehman. If only 1% of that turns into real money needing to be paid out, and recovery on the bonds was literally under 10 cents, then the actual "notional at risk" was $540 billion. As a result we have almost none of the market being used either to insure actual bonds or to place bets on the firm's demise (or health) - essentially the entire CDS marketplace exists to do exactly one thing - steal from the buyers of this "protection"!

[ Bericht 2% gewijzigd door Drugshond op 20-10-2008 20:33:54 ]

Maar de situatie lijkt me toch wel iets anders als de subprime markt. Ik bedoel: je koopt hier geen bezittingen maar je verkoopt zekerheid. En net als een verzekeraar zullen verkopers van CDO-contracten toch wel een beetje willen weten wat ze onderhanden hebben. Leningen kun je aankleden, maar de inhoud van een CDO-contract lijkt me vrij concreet.

Je merkt het al: ik probeer wanhopig wat zekerheid te vinden.

quote:dat wordt dus flink werken de komende eeuwen om het geld dat in de afgelopen weken is gemaakt echt te maken dan.Op maandag 13 oktober 2008 22:31 schreef TubewayDigital het volgende:

[..]

het geld wordt gecreerd uti het niets maar er wordt ook gewerkt/geproduceerd dus het gecreeerde geld wordt gedekt door productie in de reeele wereld

quote:Zie http://www.dtcc.com/news/press/releases/2008/tiw.phpDTCC Addresses Misconceptions About the Credit Default Swap Market

New York, October 11, 2008 – The idea that the industry lacks a central registry for over-the-counter (OTC) credit default swaps (CDS) is grossly misleading and has resulted in inaccurate speculation on a number of matters, including the overall size of the market, its role in the mortgage crisis, and the size of potential payment obligations under credit default swaps relating to Lehman Brothers. The extent to which such speculation has fueled last week’s market turmoil is difficult to determine. The facts are these:

Central Trade Registry

* In November 2006, The Depository Trust and Clearing Corporation (DTCC) established its automated Trade Information Warehouse as the electronic central registry for credit default swaps. Since that time, the vast majority of credit default swaps traded have been registered in the Warehouse. In addition, all of the major global credit default swap dealers have registered in the Warehouse the vast majority all contracts executed among each other before that date.

Size of the Market

* Reported estimates of the size of the credit default swap market have so far been based on surveys. These surveys tend to overstate the size of the market due to each party to a trade separately reporting its own side. Thus, when two parties to a single $10 million dollar trade each report their “side” of the trade, the amount reported is $20 million, which overstates the actual size by a factor of two since both reports relate to a single $10 million contract. When examining the outstanding amount of actual contracts registered in the Warehouse (not separately reported “sides”) as of October 9, 2008, credit default swap contracts registered in the Warehouse totaled approximately $34.8 trillion (in US Dollar equivalents). This is down significantly from the approximately $44 trillion that were registered in the Warehouse at the end of April this year.

Percentage of the Market Related to Mortgages

* Less than 1% of credit default swap contracts currently registered in the Warehouse relate to particular residential mortgage-backed securities. Mortgage-related index products also have some components relating to residential mortgages and, as a whole, also constitute a relatively small fraction of total credit default swaps registered in the Warehouse.

Payment Obligations Related to the Lehman Bankruptcy

* One of the many central servicing functions of the Trade Information Warehouse is to caculate payments due on registered contracts, including cash payments due upon the occurrence of the insolvency of any company on which the contracts are written. Calculated amounts are netted on a bilateral basis, and then, for firms electing to use the service, transmitted to CLS Bank (the world’s central settlement bank for foreign exchange) where they are combined with foreign exchange settlement obligations and settled on a multi-lateral net basis. Currently, all major global credit default swap dealers use CLS Bank to settle obligations under credit default swaps. It is expected that all major institutional players in the credit default swap market will use the same process for settlement by the end of 2009.

* The payment calculations so far performed by the DTCC Trade Information Warehouse relating to the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy indicate that the net funds transfers from net sellers of protection to net buyers of protection are expected to be in the $6 billion range (in U.S. dollar equivalents).

DTCC has long supported the U.S. and global capital markets as a critical part of their operational infrastructure.We stand ready to play a constructive role in whatever overall regulatory environment ultimately emerges for the credit default swap market. We do believe, however, that whatever environment emerges should be based on assessment of the facts as they stand, rather than speculation.

De afrekening van vandaag zou dus ongeveer 6 miljard dollar omvatten en niet ruim 350 miljard. We zullen zien wat er van waar is.

quote:Veel financiële instellingen hebben dit verlies al (min of meer verwerkt) Ambac volg ik redelijk on plotting course. Gevaarlijke speler..Op woensdag 22 oktober 2008 09:15 schreef beantherio het volgende:

Ik zat gisterenavond smachtend voor de tv te wachten tot alles "boem" ging, maar er gebeurde helemaal niks. Wat is erfoutgoed gegaan?

quote:Kennelijk. Volgens mij zou trouwens vandaag de afwikkeling van de CDS-verplichtingen n.a.v. het WaMu-faillisement moeten plaatsvinden. Maar het lijkt er niet op dat dat echte schokgolven teweeg gaat brengen.

quote:Check het filmpje, voor een betere uitleg.CBS

(CBS) The world's financial system teetered on the edge again last week, and anyone with more than a passing interest in their shrinking 401(k) knows it's because of a global credit crisis. It began with the collapse of the U.S. housing market and has been magnified worldwide by what Warren Buffet once called "financial weapons of mass destruction."

They are called credit derivatives or credit default swaps, and 60 Minutes did a story on the multi-trillion dollar market three weeks ago. But there's a lot more to tell.

As Steve Kroft reports, essentially they are side bets on the performance of the U.S. mortgage markets and the solvency on some of the biggest financial institutions in the world. It's a form of legalized gambling that allows you to wager on financial outcomes without ever having to actually buy the stocks and bonds and mortgages.

It would have been illegal during most of the 20th century, but eight years ago Congress gave Wall Street an exemption and it has turned out to be a very bad idea.

While Congress and the rest of the country scratched their heads trying to figure out how we got into this mess, 60 Minutes decided to go to Frank Partnoy, a law professor at the University of San Diego, who has written a couple of books on the subject.

Ask to explain what a derivative is, Partnoy says, "A derivative is a financial instrument whose value is based on something else. It's basically a side bet."

Think of it for a moment as a football game. Every week, the New York Giants take the field with hopes of getting back to the Super Bowl. If they do, they will get more money and glory for the team and its owners. They have a direct investment in the game. But the people in the stands may also have a financial stake in the ouctome, in the form of a bet with a friend or a bookie.

"We could call that a derivative. It's a side bet. We don't own the teams. But we have a bet based on the outcome. And a lot of derivatives are bets based on the outcome of games of a sort. Not football games, but games in the markets," Partnoy explains.

Partnoy says the bet was whether interest rates were going to go up or down. "And the new bet that arose over the last several years is a bet based on whether people will default on their mortgages."

And that was the bet that blew up Wall Street. The TNT was the collapse of the housing market and the failure of complicated mortgage securities that the big investment houses created and sold around the world.

But the rocket fuel was the trillions of dollars in side bets on those mortgage securities, called "credit default swaps." They were essentially private insurance contracts that paid off if the investment went bad, but you didn't have to actually own the investment to collect on the insurance.

"If I thought certain mortgage securities were gonna fail, I could go out and buy insurance on them without actually owning them?" Kroft asks Eric Dinallo, the insurance superintendent for the state of New York.

"Yeah," Dinallo says. "The irony is, though, you're not really buying insurance at that point. You're just placing the bet."

Dinallo says credit default swaps were totally unregulated and that the big banks and investment houses that sold them didn't have to set aside any money to cover their potential losses and pay off their bets.

"As the market began to seize up and as the market for the underlying obligations began to perform poorly, everybody wanted to get paid, had a right to get paid on those credit default swaps. And there was no 'there' there. There was no money behind the commitments. And people came up short. And so that's to a large extent what happened to Bear Sterns, Lehman Brothers, and the holding company of AIG," he explains.

In other words, three of the nation's largest financial institutions had made more bad bets than they could afford to pay off. Bear Stearns was sold to J.P. Morgan for pennies on the dollar, Lehman Brothers was allowed to go belly up, and AIG, considered too big to let fail, is on life support to thanks to a $123 billion investment by U.S. taxpayers.

"It's legalized gambling. It was illegal gambling. And we made it legal gambling…with absolutely no regulatory controls. Zero, as far as I can tell," Dinallo says.

"I mean it sounds a little like a bookie operation," Kroft comments.

"Yes, and it used to be illegal. It was very illegal 100 years ago," Dinallo says.

CBS, heeft het nogmaals onder de aandacht gebracht. (30-08-09)

http://www.cbsnews.com/video/watch/?id=5274961n&tag=contentBody;housing

Qua informatie voorziening mis ik nog heel wat op de Nederlandse TV