F&L Filosofie & Levensbeschouwing

Een plek om te discussiëren over filosofische vragen, filosofen, religieuze vraagstukken of religie en levensbeschouwing in het algemeen.

Om maar even een idee van Haushofer te rippen, daar waar hij begon met Hebreeuws is voor mij een inspiratie geworden om kleine digital cursussen Arabisch te geven voor zover mogelijk.

Ik begin met het alfabet en cijfers.

Subcribe op het topic doe je maar niet door een tvp, seriously you guys.

Tvp, verkapte tvp of niets toevoegende post + tvp worden allemaal zonder pardon verwijderd.

And i am a mod I can make it happen. (

(  )

)

Arabisch sprekende users:

Triggershot

HetwasietsmeteenF

Alulu

Aslama

Double-Helix

[ Bericht 4% gewijzigd door #ANONIEM op 30-05-2008 19:24:19 ]

Ik begin met het alfabet en cijfers.

Subcribe op het topic doe je maar niet door een tvp, seriously you guys.

Tvp, verkapte tvp of niets toevoegende post + tvp worden allemaal zonder pardon verwijderd.

And i am a mod I can make it happen.

Arabisch sprekende users:

Triggershot

HetwasietsmeteenF

Alulu

Aslama

Double-Helix

[ Bericht 4% gewijzigd door #ANONIEM op 30-05-2008 19:24:19 ]

Arabische alfabet om te kunnen herkennen en uitspreken:

* ت – th (als th in het Engelse three - ook uitgesproken als s)

* ج – dj (als dj in jeans – in Egypte wordt dit als g in het Engelse good uitgesproken)

* ح en ه – h (volgens de wetenschappelijke methode: ḥ en h)

* خ – ch of g, soms kh (als g van goed)

* د en ض – d (wetenschappelijk: d (dal) en ḍ (dad))

* ذ – dh, soms dz (als th in het Engels father - ook uitgesproken als z)

* س en ص – s (wetenschappelijk: s (sien) en ṣ (sad))

* ش – sj (als sj in sjaal)

* ظ – ẓ of dz

* ع – ʿ of 3 (dit teken maakt de letter waar het voor staat zwaarder van klank - indien het woord hiermee eindigt geldt dit voor de laatste letter van het woord)

* غ – gh (ongeveer als de Franse gebrouwde r zoals in Paris)

* ق – q (als k - maar achter in de keel)

* و – w of oe, u

* ی – j, y of ie

* ء (hamza) – ' (korte pauze in het woord)

* ة (ta marboeta) - als h aan het eind van een zin of als t als na dat woord een ander woord volgt en in sommige meervoudsvormen

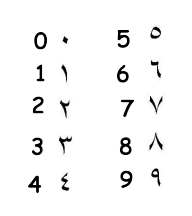

en de getallen :

Om maar mee te beginnen, Arabische alfabet heeft 28 letters en wordt van rechts naar links gelezen. Getallen daarentegen niet, schrijf je en lees je van links naar rechts.

[ Bericht 11% gewijzigd door Dagonet op 30-05-2008 19:26:52 ]

* ت – th (als th in het Engelse three - ook uitgesproken als s)

* ج – dj (als dj in jeans – in Egypte wordt dit als g in het Engelse good uitgesproken)

* ح en ه – h (volgens de wetenschappelijke methode: ḥ en h)

* خ – ch of g, soms kh (als g van goed)

* د en ض – d (wetenschappelijk: d (dal) en ḍ (dad))

* ذ – dh, soms dz (als th in het Engels father - ook uitgesproken als z)

* س en ص – s (wetenschappelijk: s (sien) en ṣ (sad))

* ش – sj (als sj in sjaal)

* ظ – ẓ of dz

* ع – ʿ of 3 (dit teken maakt de letter waar het voor staat zwaarder van klank - indien het woord hiermee eindigt geldt dit voor de laatste letter van het woord)

* غ – gh (ongeveer als de Franse gebrouwde r zoals in Paris)

* ق – q (als k - maar achter in de keel)

* و – w of oe, u

* ی – j, y of ie

* ء (hamza) – ' (korte pauze in het woord)

* ة (ta marboeta) - als h aan het eind van een zin of als t als na dat woord een ander woord volgt en in sommige meervoudsvormen

en de getallen :

Om maar mee te beginnen, Arabische alfabet heeft 28 letters en wordt van rechts naar links gelezen. Getallen daarentegen niet, schrijf je en lees je van links naar rechts.

[ Bericht 11% gewijzigd door Dagonet op 30-05-2008 19:26:52 ]

Goed idee. Iemand uit Iran wilde mij ooit Perzisch leren, en het Arabisch alfabet. En hij had wel wat. Ik moet zeggen, het viel niet mee. Zo klein, en al die friemeltjes, ik vond het lastig uit elkaar houden. En dan die verschillende vormen. En dan bedacht dat boek ook nog dat het tof was om speciale ligaturen voor miim + miim te gebruiken b.v. En toen heb ik het stiekem opgegeven.  Maar goed, nog een poging en tvp dus.

Maar goed, nog een poging en tvp dus.

Daher iſt die Aufgabe nicht ſowohl, zu ſehn was noch Keiner geſehn hat, als, bei Dem, was Jeder ſieht, zu denken was noch Keiner gedacht hat.

Even een zeurpuntje: Hiermee bedoel je ‘net als in het Nederlands’? Want ik vind dat ‘wij’ getallen eigenlijk ‘van rechts naar links’ schrijven. B.v., als je ze uitlijnt, dan doe je dat zo:quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 17:22 schreef Triggershot het volgende:

Om maar mee te beginnen, Arabische alfabet heeft 28 letters en wordt van rechts naar links gelezen. Getallen daarentegen niet, schrijf je en lees je van links naar rechts. :)

| 1 2 3 4 | 13 211 15 |

Hoe groter een getal wordt hoe verder het aan de linkerkant uitdijt. Dus, in concreto: 2000 in het Arabisch is ٢٠٠٠? En niet ٠٠٠٢?

Daher iſt die Aufgabe nicht ſowohl, zu ſehn was noch Keiner geſehn hat, als, bei Dem, was Jeder ſieht, zu denken was noch Keiner gedacht hat.

in concreto: 2000 in het Arabisch is ٢٠٠٠quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 18:14 schreef Iblis het volgende:

[..]

Even een zeurpuntje: Hiermee bedoel je ‘net als in het Nederlands’? Want ik vind dat ‘wij’ getallen eigenlijk ‘van rechts naar links’ schrijven. B.v., als je ze uitlijnt, dan doe je dat zo:

[ code verwijderd ]

Hoe groter een getal wordt hoe verder het aan de linkerkant uitdijt. Dus, in concreto: 2000 in het Arabisch is ٢٠٠٠? En niet ٠٠٠٢?

de ''normale'' cijfers zijn toch Arabische cijfers,de anderen Hindoe cijfers ofzo???

Op zaterdag 23 juni 2007 18:54 schreef MASD het volgende:

Double-Helix is mijn held vandaag! _O_

Double-Helix is mijn held vandaag! _O_

Ik heb de Arabische cijfers helaas nooit geleerd. Tunesie is het enige land van de Arabische wereld waar men nergens op school deze cijfers hanteert maar de internationale cijfers die wij ook in Europa kennen.

Goed idee trouwens trig.

Misschien ook een leuk idee als je er gelijk wat omheen vertelt zoals bijv verschillen tussen de verschillende dialecten en het echte Arabisch, fosha. Zodat men gelijk een beter beeld krijgt wat je nou precies kan verwachten als je een woordje Arabisch spreekt en op vakantie gaat naar een Arabisch land.

Goed idee trouwens trig.

Misschien ook een leuk idee als je er gelijk wat omheen vertelt zoals bijv verschillen tussen de verschillende dialecten en het echte Arabisch, fosha. Zodat men gelijk een beter beeld krijgt wat je nou precies kan verwachten als je een woordje Arabisch spreekt en op vakantie gaat naar een Arabisch land.

X

@ Double-Helix: Dat zei mijn Arabische lerares ook inderdaad. Dat eigenlijk de internationale cijfers, die wij gebruiken, Arabisch zijn en de cijfers waarvan men veronderstelt dat die Arabisch zijn eigenlijk van de Perzen is overgenomen.

X

Ze zijn overgenomen van de Hindoe's alhoewel ik niet weet of het exact in bovenstaande vorm is genomen, hoe dan ook, zo gebruikt men het in o.a Syrie, Libanon en Irak.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 19:00 schreef Double-Helix het volgende:

de ''normale'' cijfers zijn toch Arabische cijfers,de anderen Hindoe cijfers ofzo???

Ok, zal het eerst volgenden 'stof' zijn wat ik zal posten.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 19:01 schreef Alulu het volgende:

Ik heb de Arabische cijfers helaas nooit geleerd. Tunesie is het enige land van de Arabische wereld waar men nergens op school deze cijfers hanteert maar de internationale cijfers die wij ook in Europa kennen.

Goed idee trouwens trig.

Misschien ook een leuk idee als je er gelijk wat omheen vertelt zoals bijv verschillen tussen de verschillende dialecten en het echte Arabisch, fosha. Zodat men gelijk een beter beeld krijgt wat je nou precies kan verwachten als je een woordje Arabisch spreekt en op vakantie gaat naar een Arabisch land.

Soorten en verschillen in Arabisch :

quote:Classical Arabic, also known as Qur'anic Arabic, is the language used in the Qur'an as well as in numerous literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times (7th to 9th centuries).

Classical Arabic is often believed to be the parent language of all the spoken varieties of Arabic, but recent scholarship, such as Clive Holes' (2004), questions this view, showing that other Old North Arabian dialects were extant in the 7th century and may be the origin of current spoken varieties.

Modern Standard Arabic

Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the literary standard across the Middle East and North Africa, and one of the official six languages of the United Nations. Most printed matter–including most books, newspapers, magazines, official documents, and reading primers for small children–is written in MSA[citation needed]. "Colloquial" Arabic refers to the many national or regional varieties derived from Arabic spoken daily across the region and learned as a first language. These sometimes differ enough from each other to be mutually incomprehensible. They are not typically written, although a certain amount of literature (particularly plays and poetry) exists in many of them. Literary Arabic or classical Arabic is the official language of all Arab countries and is the only form of Arabic taught in schools at all stages.

The sociolinguistic situation of Arabic in modern times provides a prime example of the linguistic phenomenon of diglossia — the use of two distinct varieties of the same language, usually in different social contexts. Educated Arabic-speakers are usually able to communicate in MSA in formal situations across national boundaries — thus, MSA is a classic example of a Dachsprache. This diglossic situation facilitates code-switching in which a speaker switches back and forth between the two varieties of the language, sometimes even within the same sentence. In instances in which highly educated Arabic-speakers of different nationalities engage in conversation but find their dialects mutually unintelligible (e.g. a Moroccan speaking with a Lebanese), they are able to code switch into MSA for the sake of communication.

Although closely based on Classical Arabic (especially from the pre-Islamic to the Abbasid period, including Qur'anic Arabic), literary Arabic continues to evolve. Classical Arabic is considered normative; modern authors attempt (with varying degrees of success) to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms laid down by Classical grammarians (such as Sibawayh), and to use the vocabulary defined in Classical dictionaries (such as the Lisan al-Arab.)

[edit] Switch from Classical Arabic to MSA

In spite of the romantic and variously successful attempts of modern Arab authors to follow the syntactic and grammatical norms of Classical Arabic, the exigencies of modernity have led to the adoption of numerous terms which would have been mysterious to a Classical author, whether taken from other languages (eg فيلم film) or coined from existing lexical resources (eg هاتف hātif "telephone" < "caller").

Structural influence from foreign languages or from the vernaculars has also affected Modern Standard Arabic: for example, MSA texts sometimes use the format "X, X, X, and X" when listing things[citation needed], whereas Classical Arabic prefers "X and X and X and X", and subject-initial sentences may be more common in MSA than in Classical Arabic[citation needed].

For all these reasons, Modern Standard Arabic is generally treated as separate language in non-Arab sources. Arab sources generally tend to regard MSA and Classical Arabic as different registers of one and the same language. Speakers of Modern Standard Arabic do not always observe the intricate rules of Classical Arabic grammar. Modern Standard Arabic principally differs from Classical Arabic in three areas: lexicon, stylistics, and certain innovations on the periphery that are not strictly regulated by the classical authorities. On the whole, Modern Standard Arabic is not homogeneous; there are authors who write in a style very close to the classical models and others who try to create new stylistic patterns. Add to this regional differences in vocabulary depending upon the influence of the local Arabic varieties and the influences of foreign languages, such as French in North Africa or English in Egypt, Jordan, and other countries.[1]

] Regional variants

MSA is used uniformly across the Middle East, but some regional variations exist due to influence from the spoken vernaculars. People who "speak" MSA during interviews often give away their national or ethnic origins by their pronunciation of certain phonemes (e.g. the realization of the Classical jīm ج (/dʒ/) as /g/ by Egyptians, and as /ʒ/ by Lebanese), and by mixing between vernacular and Classical words and forms. Classical/vernacular mixing in formal writing can also be found (e.g. in some Egyptian newspaper editorials).

quote:

Tvp.quote:Tvp, verkapte tvp of niets toevoegende post + tvp worden allemaal zonder pardon verwijderd.

Tot nu toe verkeerde ik altijd onder de indruk dat "onze" cijfers Arabische cijfers zijn en ze in het Arabisch dus hetzelfde zijn.. Wie kan me dit uitleggen?

Hier staan twee puntjes boven, dan spreek je het uit als een gewone 't'. Als er drie puntjes boven staan dan dien je het uit te spreken als een "th" als in het Engels "three". En wanneer wordt deze letter uitgesproken als een "s"?quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 17:22 schreef Triggershot het volgende:

<font size="4"> * ت – </font> th (als th in het Engelse three - ook uitgesproken als s)

Ik denk omdat voor deze getallen werd gebruikt men in Europa Romeinse getallen gebruikte.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 20:36 schreef Alicey het volgende:

Tot nu toe verkeerde ik altijd onder de indruk dat "onze" cijfers Arabische cijfers zijn en ze in het Arabisch dus hetzelfde zijn.. Wie kan me dit uitleggen?

Je hebt gelijk, had 4e letter van het alfabet moeten zijn niet 3e, wrs gewoon een puntje vergeten. 4e alfabet spreek je soms wel dialectisch uit als een 's', denk aan Yowm Al-Isnain/ Yewm Al-Ithneen bijvoorbeeld.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 20:38 schreef Tevik het volgende:

[..]

Hier staan twee puntjes boven, dan spreek je het uit als een gewone 't'. Als er drie puntjes boven staan dan dien je het uit te spreken als een "th" als in het Engels "three". En wanneer wordt deze letter uitgesproken als een "s"?

Wat ik bedoel is dat de Arabische cijfers in dit topic heel anders zijn dan onze 0, 1, 2 etc. t/m 9.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 20:58 schreef Triggershot het volgende:

[..]

Ik denk omdat voor deze getallen werd gebruikt men in Europa Romeinse getallen gebruikte.

Ik bedoelde eik dat het aangeven van een hoeveelheid van getallen zonder te hoeven rekenen gebracht is naar Europa door de Arabieren.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 21:57 schreef Alicey het volgende:

[..]

Wat ik bedoel is dat de Arabische cijfers in dit topic heel anders zijn dan onze 0, 1, 2 etc. t/m 9.

Hmm.. Je bedoelt dat de Arabieren zeg maar het decimale stelsel hebben gebracht, maar dat wij vervolgens zelf grapzige symbooltjes hebben verzonnen voor de digits?quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 22:00 schreef Triggershot het volgende:

[..]

Ik bedoelde eik dat het aangeven van een hoeveelheid van getallen zonder te hoeven rekenen gebracht is naar Europa door de Arabieren.

Jup.quote:Op vrijdag 30 mei 2008 22:04 schreef Alicey het volgende:

[..]

Hmm.. Je bedoelt dat de Arabieren zeg maar het decimale stelsel hebben gebracht, maar dat wij vervolgens zelf grapzige symbooltjes hebben verzonnen voor de digits?

Tjeempie, weer iets geleerd.quote:

Off-topic hoor, maar heb je nog referenties naar hoe onze cijfers dan wel ontstaan zijn, wie ze heeft bedacht etc.?

Over het ontstaan van zulke cijfers zijn er verschillen.

De getallen in het midden oosten worden gebruikt zijn juist niet van arabische afkomst, wel uit Indie! vreemd maar waar!

dus indisch: ۰ ۱ ۲ ۳ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ۸ ۹

Volgens de Arabische wikipedia zijn de arabische cijfers (dus die in het westen en de rest van de wereld worden gebruikt) gemaakt door een man uit Noord Afrika (Marokko) die glazen maakte. Dat stond in een recent onderzoek over het ontstaan van zulke cijfers.

Als het goed is, is dit hier te lezen:

je ziet dat ieder cijfer staat voor het aantal hoeken.

bronnen

http://ar.wikipedia.org/w(...)B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A9

http://lescorpiondechair.(...)ocumentsannexes.html

De getallen in het midden oosten worden gebruikt zijn juist niet van arabische afkomst, wel uit Indie! vreemd maar waar!

dus indisch: ۰ ۱ ۲ ۳ ٤ ٥ ٦ ٧ ۸ ۹

Volgens de Arabische wikipedia zijn de arabische cijfers (dus die in het westen en de rest van de wereld worden gebruikt) gemaakt door een man uit Noord Afrika (Marokko) die glazen maakte. Dat stond in een recent onderzoek over het ontstaan van zulke cijfers.

Als het goed is, is dit hier te lezen:

Het gaat dus om deze cijfers:quote:Selon une tradition populaire, encore tenace en Egypte et en Afrique du Nord, les chiffres « arabes » seraient l’invention d’un vitrier géomètre originaire du Maghreb..

je ziet dat ieder cijfer staat voor het aantal hoeken.

bronnen

http://ar.wikipedia.org/w(...)B1%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A9

http://lescorpiondechair.(...)ocumentsannexes.html

verlegen :)

|

|